Elections take place on June 5 to more than 900 seats in various types of local councils, 12 seats in the European Parliament as well as two seats in Dáil Eireann. Success for the opposition in both by-elections may well have direct consequences for the stability of the government although as long as the Green party remains in government, its majority seems safe. What is certain is that the local and European Parliament elections will also be analysed and interpreted largely for their significance with respect to national politics. Most importantly, these will be seen as indicating the national standing of the parties in much more concrete terms than can be given by opinion polls. Is Fianna Fáil really as unpopular as recent TNS/Irish Times and Red C/Sunday Business Post polls have suggested? Is Fine Gael at support levels not seen since the heyday of Garret Fitzgerald? And is Labour once again winning the sort of support that Dick Spring squandered in 1992? A result which reinforces the findings of recent polls will have pundits pondering a range of possibilities, from the downfall of the current government to the long-awaited realignment of the whole party system. Of course these campaigns will tell us something about morale in the various parties, and who wins the seats, particularly the local seats, will have implications for the candidate pool at forthcoming general elections. However inappropriate it may seem to many people, local councils still provide the apprenticeship for aspiring national politicians.

How justified is this essentially national interpretation of these elections? Do votes to send three representatives to Brussels from the Ireland-East constituency, let alone those to determine the make up of Westmeath County Council really carry significant implications for national politics as a whole? There is a strong argument to be made that all such elections are determined primarily by the state of party competition in the main arena of politics here – the politics of government and opposition in the Dáil. There are several reasons for this. One is that the campaigns themselves will place these elections in the context of national politics. Opposition parties will all call on voters to give the government a bloody nose, to use the opportunity of a vote for a seat on Louth County Council, or even Drogheda UDC, to express their views on government policy, such as the treatment of the banks, the so-called ‘pension levy’ on public employees, or the dithering over medical cards for the elderly. There will also be the hint that such behaviour could even unseat the government, or at least lead Fianna Fáil to change the men and women at the top.

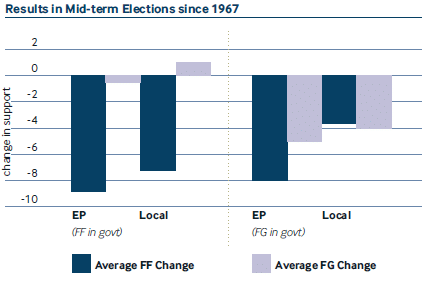

A second reason is that the same parties fight all elections and the results at national level look much the same regardless of the type of election and the responsibilities and performance of the bodies being elected. If we summarise results since the late 1960s, Fianna Fáil has always been the largest party in general, local and in European Parliament elections; Fine Gael has come second, usually by a distance, and Labour a poor third. Regardless of the type of election, Labour and Fine Gael have won very similar levels of support over the last 40 years or so, with Labour getting 11-12% in each contest while Fine Gael averages 31% in local and general elections as against 27 in European Parliament elections. Fianna Fáil does not fit this pattern so well, averaging 44% in general elections, but 39% in local elections and only 35% in European Parliament elections. One reason for that party’s relative weakness in local and European Parliament elections is that Fianna Fáil has generally been in government, and local and European Parliament elections have taken place ‘mid term’. If these elections are referendums on the government, Fianna Fáil has usually been in the firing line. In its rare periods in opposition, the gap between its general election and local election support has been smaller. When Fine Gael was in government its mid-term election support fell significantly below that won in the previous general election. However, Fianna Fáil’s European Parliament performance is almost always bad, the party dropping 9% below its previous general election support level when in government and 8% when in opposition. The 1999 elections were exceptional as Fianna Fáil, although in government, maintained the level of support it won in the 1997 general election. Significantly, however, Fianna Fáil was extraordinarily popular at the time: almost 60% were satisfied with the government and 67% of voters were satisfied with Bertie Ahern as Taoiseach. These levels of satisfaction were common in 1997-2002, but rarely seen at any previous, or subsequent, time.

A third reason is the evidence from many countries showing how party choice in sub-national elections is typically determined by matters which are outside the competence of the bodies being elected. This is not always the case. It can be shown that voters in federal systems can make distinctions between what is done by their state governments and what is done by the federal government. However, where this is so, in the US and Canada, the political systems are long-established and there are media environments that facilitate public understanding of different competences. In contrast, there is evidence that electoral choice to the new Scottish parliament is determined more by matters that are the preserve of the Westminster parliament than those which are the preserve of the assembly in Edinburgh. Choice in European Parliament elections has been much studied across the EU and the evidence is clear that voters make little distinction between parties based on the competences of the European Parliament as against their national parliaments.

The nature of local government in Ireland does not facilitate a form of politics that is oriented towards local decision-making and accountability. Local councils have relatively few powers, and even fewer sources of funding that are independent of national government. Most people know that we have a Fianna Fáil-led government, but it is unlikely that anything like so many know how majorities in local councils are constructed; in fact, apart from voting for local mayors, council votes typically show a much less rigid party system than we are used to in the Dáil. This makes it hard for voters to hold parties to account for local affairs. In the case of the European Parliament, this lack of collective accountability is even more severe. Although the European Parliament is a very significant actor in EU decision making, most voters have a very limited appreciation of what goes on there.

“The evidence is clear that voters make little distinction between parties based on the competences of the European Parliament as against their national parliaments.”

There are counter arguments to soften this predominantly national vision. Party campaigns are not solely national. Even leaving aside the fact that the Fianna Fáil logo seems to have gone missing on the posters of many of its nominees on this occasion, candidates do give a lot of attention to local matters in their campaigns. Some exhort the voter to ‘vote local’, perhaps dismissing national politics. Non-party candidates are more successful in local elections than in general elections. It is also a mistake to think that because a party’s vote across different elections is stable, the same people are voting for it. In a recent book on local elections in Ireland [All Politics is Local], Liam Weeks and Aodh Quinlivan point out that there has been a very low correlation between Fianna Fáil’s local and general election support at Dáil constituency level – as if it is not winning votes from the same people in each contest. In contrast, the Fine Gael vote is much more stable. It is possible that Fianna Fáil picks up general election votes from people who would not support it in other elections, because they see it as best able to deliver stable government in the Dail, a point the party has always emphasized, even after Charles Haughey abandoned its anti-coalition stance.

We certainly do see voters switching parties at local and European elections, returning to the fold at the next general election. Evidence from the 2002-2007 Irish election study, which interviewed the same people up to five times across this period, showed those who voted Fianna Fáil in the general election of 2002 were more than twice as likely as those who voted Fianna Fáil in the local elections of 2004 to support that party again in 2007. Even among those who voted for the party in 2002 and 2007, a substantial minority cast their favours elsewhere in 2004. The same is true when we substitute the European Parliament election for the local election. We might see this as revealing a homing instinct among members of the Fianna Fáil tribe, but it may also indicate a separation of the different sorts of elections by some voters, who select different horses for different courses. The voters themselves claim candidate factors are more important in local elections than general elections, although the difference is not large. This may provide some small crumbs of comfort for the embattled members of The Republican Party when the results are declared.

Michael Marsh is professor of comparative political behaviour and dean of the faculty of arts, humanities and social sciences in TCD