The Westminster oath declares:

“I … swear by Almighty God that I will be faithful and bear true allegiance to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth, her heirs and successors, according to Law. So help me God”.

British oaths have a troublesome history in Ireland they‘re never insuperable but they always generate a row and a test for the conscience, for a while.

In late February Leo Varadkar, Taoiseach, called on Sinn Féin to take the oath and with it their six – soon to be seven – Westminster seats “to make things better for Ireland”. Naturally, like all other voguish red-liners Sinn Féin have ruled it out. A spokesman said: “This is not even a topic of discussion within the party. We are an abstentionist party, and we are mandated to abstain from Westminster by the people who vote for us”.

Writing in the Guardian Polly Toynbee noted: “For now, everyone says no. The winners might be those who make the biggest U-turn sacrifice for the sake of their country. If only they could mutter the loyal oath (they could always rescind it later) they would arrive in parliament as a cavalry of saviours of Ireland – and incidentally Britain”.

Admittedly the true Brit-hater would prefer to let them stew a little, or lot, longer in their brew of contradictory shibboleths.

But what is the pedigree of abstentionism?

In 1921 De Valera refused to recognise the Anglo-Irish Treaty, ending the War of Independence, as it involved an oath of allegiance prescribed by the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921. Five years later, after the resultant civil war, he abjured his objections subscribing to an identical formula but claiming that “he had taken no oath of allegiance to the British monarch” on entering Dáil Éireann. The oath in 1921 and 1926 was: “I will be faithful to HM King George V. . . in virtue of the common citizenship of Ireland with Great Britain and her adherence to and membership of. . . the British Commonwealth of Nations”.

In power from 1932, de Valera amended the Free State’s constitution to allow him to introduce any constitutional amendments irrespective of whether they clashed with the Anglo-Irish Treaty, and then to remove Article 17 of the constitution which required the taking of the Oath. Certainly the oath for De Valera was of fidelity not allegiance. Less of a lump to swallow than now.

The idea of Irish nationalists abstaining from Westminster was in fact first suggested in the 1840s by Thomas Davis and Daniel O’Connell, though ultimately they felt that MPs sitting could not withdraw from Westminster without breaking the oath of office they had taken upon election. It was endlessly debated by Home Rule leader Charles Stewart Parnell in the 1870s.

Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa (in 1869) and John Mitchel (twice in 1875) were returned as independent nationalists at by-elections in Tipperary though O’Donovan Rossa was in prison at his election and Mitchel in exile. The results were invalidated.

Michael Davitt set the tone and strategy – he was so fed up with the British system that he withdrew from Parliament in 1899 explaining: “I have for years tried to appeal to the sense of justice in this house of Commons on behalf of Ireland. I leave, convinced that no just cause, no cause of right, will ever find support from this house of Commons unless it is backed up by force”.

Arthur Griffith, the original founder of ‘Sinn Féin’ in 1905, advocated withdrawal from the British Parliament as a tactic following the strategies of Hungarian and Czech nationalists in the Austrian Imperial Council in the 1860s. He considered that the Irish Home Rule Party shouldn’t go to Westminster but a council of 300 should meet in Dublin and usurp, by peaceful means, so much of the powers of government as it could. This seemed a good plan.

12 Tory MPs voted against the government to demand a meaningful Commons vote on the final Brexit deal. So things would be tight on Corbyn’s customs-union amendment. [Sinn Féin’s] four or five votes would swing it.

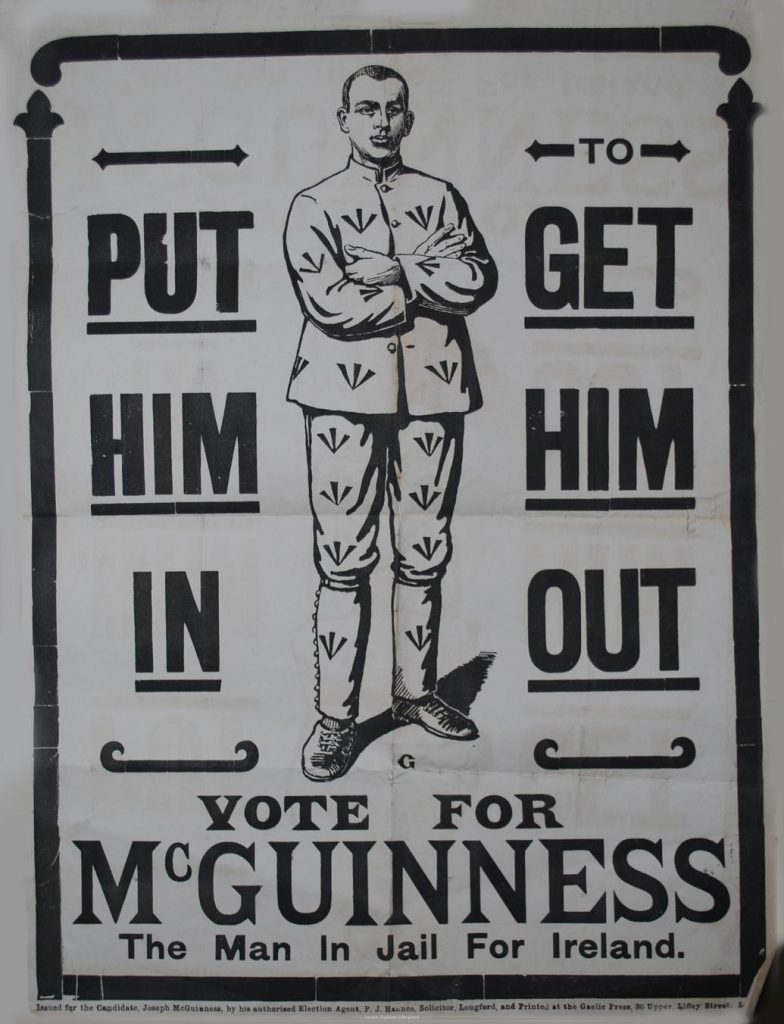

Joseph McGuinness was the first ‘Sinn Féin’ abstentionist MP following a by- election in Longford South in May 1917. Even if he had wanted to take his seat, he would not have been able to do so as he was a prisoner in Lewes for his role in the previous year’s Easter Rising.

In 1919, the 69 Sinn Féin MPs elected to Westminster in 1918 refused to take their seats there and instead constituted themselves in Dublin as the the first Dáil – the legitimate parliament of the short- lived Irish Republic.

At its 1970 Ard Fheis Sinn Féin divided on whether or not to reverse its long-standing policy of refusing to take seats in Dáil Éireann. The split created two parties: ‘Sinn Féin’ and an anti-abstentionist rival to be known as ‘Official Sinn Féin which ultimately split between ‘the Workers’ Party’ and a group that fused with the Labour Party. The abstentionist party was initially referred to as ‘Provisional’ Sinn Féin, but after 1982 it was known simply as ‘Sinn Féin’; it continued to abstain from taking seats won in all institutions.

In 1986 ‘Provisional’ Sinn Féin split, as in 1970, over whether to take seats in Dáil Éireann. The larger group led by Gerry Adams abandoned abstentionism, while Republican Sinn Féin (RSF), led by Ruairí Ó Brádaigh retained it. Sinn Féin’s first sitting TD was Caoimhghín Ó Caoláin in Cavan–Monaghan in 1997. It abandoned its abstention from Dáil Éireann and from Stormont in 1998.

In the late 1980s Sinn Féin’s abstentionist MPs discovered that under rules to accommodate conscientious objectors and republicans they could avail of facilities at Westminster to represent their constituents, though they do not qualify for a salary.

After the 1997 Westminster election the Speaker of Parliament, Betty Boothroyd, banned Sinn Féin from the facilities unless members took the Oath of Allegiance. That was overturned ve years later, although periodically Conservative and Unionist MPs and their allies in the press vituperate about the issue. Sinn Féin MPs contrary to a widespread impression do not receive a Westminster salary.

In June 2017 Gerry Adams was explicit at the Belfast count centre following the party’s successes in the UK general election that there was no prospect whatsoever of Sinn Féin abandoning its abstentionist stance even if Jeremy Corbyn came looking for his old Sinn Féin friends’ help.

“What kind of self-respecting Irish republican would ask anyone to ignore their electoral mandate and swear loyalty to the English Queen or legitimise the British Parliament’s role in Ireland?

The electorate realise that the parliament in London does not work for them and it doesn’t stand up for their best interests. Brexit has been a shining example of that reality. Their electoral decision should be acknowledged and upheld”.

It might have been the 1840s or Michael Davitt again. And Sinn Féin appears united, as usual, on this. Replying to the Toynbee article in the Guardian on 7 March Paul Maskey MP concurred, giving the “Republican perspective”: “For 100 years now, Irish republicans have refused to validate British sovereignty over the island of Ireland by sitting in the parliament of Westminster”.

However, while Griffith did not regard abstention as a principle in itself, but as a way of demonstrating the principle of self-determination and national independence, today’s Sinn Féin have elevated a political tactic into a long-standing, fundamental principle that cannot be breached by their elected MPs.

This is unwise and confused: there is no higher principle for a political party than furthering the common good and the good of their electorate.

The difference here is that Sinn Féin may have a swing vote. The government has a working majority of 13 in the house of Commons, once you include support from the Democratic Unionist party. BBC ‘Newsnight’ reported in late February that seven pro-Brexit Labour MPs could support the government on Jeremy Corbyn’s customs union amendment, giving the government a majority of 27. This means 14 Conservatives would have to rebel against the government to win the vote. In December last year, 12 Tory MPs voted against Mrs May to demand a meaningful Commons vote on the nal Brexit deal. So things would be tight. Four or five votes would swing it.

The majority against the UK staying in the customs union is around the size of the Sinn Féin representation, though of course they need to be careful that their presence does not generate a backlash from squeamish British MPs. Winning that vote might quickly consign Theresa to historical foot-notedness and ultimgtely propel Cornyn’s ultra-Sinn-Féin-friendly Labour to power.

Sinn Féin have an opportunity to throw back nearly 800 years of constitutional abuse in the face of Little Englanders and to turn an oath into a meaningless formula on an issue far more conducive to the common good and international good than the one which temporarily exercised the conscience of morally flexible, De Valera in 1921. If it grates, they can think of it as revenge.

Abstentionism makes sense if it highlights that you are being kept from power. When taking your seat actually gives you power, you take it. Neither history nor any principle detains you.

Michael Smith