By David Burke.

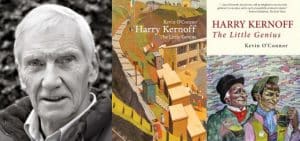

The Liffey Press has just republished Kevin O’Connor’s 2012 gem, ‘Harry Kernoff, The Little Genius’, the only full-length biography of the painter. The original edition became impossible to acquire years ago. The reprint is lavishly illustrated with hundreds of Kernoff’s pictures, made possible by years of detective work on the part of O’Connor, who managed to track so many of them down. A few dozen are reproduced in colour.

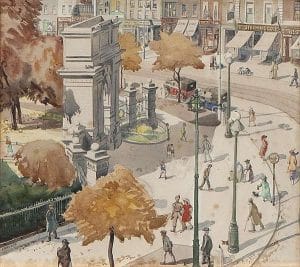

Kernoff’s family fled from Vitebsk, Russia, during the 1890s. The artist was born in London in 1900 and moved to Dublin in 1914. He spent most of his life without the recognition he so richly deserved, yet continued to paint the world around him. O’Connor captures the essence of the man thus: “He lived among and studied [Dublin’s] people, recording them in their infinite variety and was rivalled only by James Joyce in bequeathing a narrative of the city. As Joyce departed shortly after turn-of-the-century, Kernoff was left with the clear palette to record Dublin’s complexion as it changed with the century. By birth a Londoner, by family Russian, by religion Jewish, his paintings show iconic respect for those who impacted upon history in revolutionary times leavened with warm affection for the ordinary people who suffer the history”.

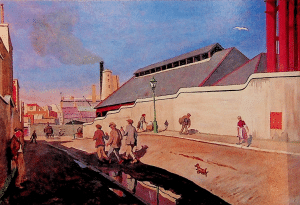

One of his works, Misery Hill (1943), depicts the “despair of man who props his arse against the wall, a common posture of the time, his entire demeanour one of defeat”, as O’Connor puts it. “Other men, no better off, are followed by Kernoff’s cheerful poodle, a common whimsey in his work. Another man carries a sack of coal while a woman pushes a handcart of offal stew, another woman passes a poster Vote Labour.

The area known as Misery Hill was on a long stretch of road faced by men from the slums hoping for a day’s work unloading ships. Unusual for the time, its realism was of a poverty largely ignored by most of his contemporaries, with the exception of George Collie. Indeed, it may be seen as another iconic painting, given the official denial of such poverty. Those that lived on state salaries were consoled by the emigration of males, a safety-valve on civic unrest. These particular paintings by Kernoff did not prove popular.

In time, the district of Misery Hill would become so painful to urban planners as to be raised during the Celtic Tiger boom years of 2000, replaced by a New Dublin of hotels, walkways and desirable apartments with sea views-modelled on the Wall Street area of New York. But even that became fatally prescient as a model in the financial downturn of 2008, when the grandiose schemes were abandoned as the country coped with bankruptcy”.

Kernoff began to receive recognition for his talent towards the end of his life. O’Connor’s book plants him among the greats of the 20th century. Harry Kernoff died in 1974.