By Frank Armstrong.

Literary deities loom over Ireland like US Presidents carved into Mount Rushmore. It isn’t philosophers, engineers, chefs, painters or even composers who summoned the Irish nation, but poets. Yet conversely their hovering presence barely registers; just as most contemporary Florentines scurry about unmoved by Brunelleschi’s dome, few here look to the sky in awe.

Poets build bridges of a more indeterminate kind than engineers. As W.H. Auden writes in a poem occasioned by the death of William Butler Yeats: “Mad Ireland hurt you into poetry. / Now Ireland has her madness and her weather still, / For poetry makes nothing happen”.

Auden goes too far with that dismissal of poetry – whatever about his contemptuous view of Ireland – correcting himself by acknowledging a few lines later: “it survives / a way of happening, a mouth”. This ‘way of happening’ is in the realm of quantum uncertainty where the extraordinary occurs: coincidences beyond logic, or the ill-defined emotion generated by a sight of great aesthetic beauty. Poetry does not fit with classical renderings of reality, the routines of life and the seemingly static laws of nature are defied. It is unsurprising that poets, Yeats foremost, should dabble in the occult and mysticism, scouring every system of thought, even the eccentric, for explanations for the mysteries they encounter.

June 13th 2015 is the 150th anniversary of W.B. Yeats. Born in Sandymount he spent much of his adult life in London, but moved permanently to Ireland after the War of Independence, purchasing a former tower house, Thoor Ballylee, in County Galway where he “paced upon the battlements and stared” at the birth pangs of the Irish state.

Yeats will always be identified with County Sligo, the home of many of his ancestors. Innisfree on Lough Gill, Lissadell, ‘far off Rosses’, Knocknarea and Ben Bulben under which he is buried form the mythical backdrop to his Romantic musing. The riveting landscape triggered imaginative contemplation perhaps unsurpassed in the English language: “Come away oh Human Child / To the waters and the wild / With a fairy hand in hand / For the world’s more full of weeping than you can understand”. The enchanting surroundings engendered Yeats’ poetry but simultaneously he made that landscape poetic. When we view immanent Ben Bulben now we are to some extent honouring the songlines that brought its majesty a reality apart. But for all his evocations of that county, in his descriptions the people are more ethereal than real, moulded in the fairy-realm of his imagination. A far cry from the gritty characters in Joyce’s ‘Dubliners’.

Like rebellious children questioning the authority of their father, most of the Irish literary pantheon have had a difficult relationship with their homeland, often preferring exile and ruminating on it from afar. Beckett went so far to write in French to escape the excesses of English, to write “without style”. But Yeats stayed and grew embittered that the nation did not accord him the accolades he felt his due. Perhaps he aspired to a presidential role similar to that later bestowed on Vaclav Havel when the Czechs gained their independence after the fall of the Iron Curtain. But he probably would have found delinquencies to fulminate against. Politics is the art of the possible, its grubby affairs a torment to the idealist.

Long before independence Yeats was bemoaning a Romantic Ireland dead and gone and castigating those that fumbled in their greasy till. But the lofty aspiration he had for his country was always doomed to failure, like his enduring affection for Maud Gonne which he finally consummated unsatisfactorily in later life before soon proposing to her daughter. Independent Ireland could never reach his expectations, a romantic relationship has ultimate failure encoded in its DNA.

Crucially Yeats came from the Protestant Ascendancy, “the men of Burke and of Grattan”, and to many among the ascendant Catholic nation who inherited the independent state he had only a shallow claim to being Irish. This separation worked both ways as the poet who initially embraced and breathed life into Irish nationalism through the cultural revival and plays such as Cathleen ni Houlihan, later identified himself with an aristocracy that he saw as providing a natural leadership for a Creole nation.

Here he fought a losing battle against the enduring tradition of republicanism that rejected aristocracy and prized equality and democracy. He also contended with the powerful force of sectarianism that would not contemplate Yeats and his caste at the helm. For many hard-bitten Catholics who retained a collective memory of the privations of the Penal Laws and the Famine, independence was an opportunity to build a Catholic state for a Catholic people.

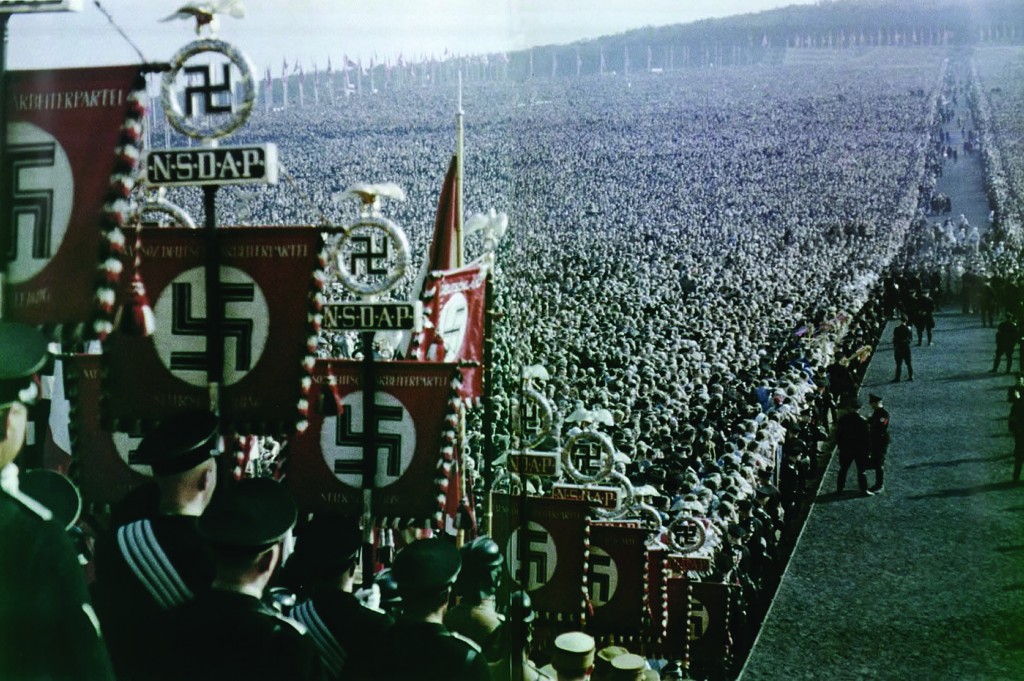

The inter-war period (1918-39) beheld terrible years of fear, poverty and continued conflict in Europe that foreshadowed the cataclysm of World War II. In the immediate aftermath of World War I Yeats wrote prophetically: “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold; / Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world, / The blood-dimmed tide is loosed”. In response to what he perceived as the failings of democracy he chose a reactionary Right as opposed to an egalitarian Left which, as he saw it, would brutally sweep aside an aristocratic elect and usher in a doomed era of materialism. This made Yeats sympathetic to fascism and perhaps even Nazism.

In his exploration of the ill-defined ideology of fascism the historian Roger Eatwell writes: “Fascism has become a latter-day symbol of evil, like the Devil in the Middle Ages. Demonising all aspects of fascism, a founding form of Political Correctness, has its uses. But failure to take fascism seriously as a body of ideas makes it more difficult to understand how fascism could attract a remarkably diverse following in some countries”. We might therefore talk of fascisms, and see them in historical context: a reaction to the chaos unleashed by the Great War and the responsibility of rampant capitalism for the Great Depression as well as the shocking excesses of triumphant Marxism in Russia. To many inter-war intellectuals democracy was failing and the collectivist ideology of Communism did not respect the individual. Also, it should not necessarily be conflated with anti-Semitism, especially the genocidal character it assumed, which had a far longer history and was not initially a feature of Mussolini’s approach.

A recent biography of Yeats, ‘Blood Kindred: W.B. Yeats, The Life, The Death, The Politics’ by W.J. McCormack outlines aspects of Yeats’ fascist sympathies. He provides details of Yeats’ letter of thanks to Freidrich Krebs, Oberburgmeister of Frankfurt, acknowledging receipt of an award in 1934, his public approval of Nazi legislation depriving Jews of their property in 1938, and aspects of his anti-Semitism. McCormack concludes that Yeats was a fellow traveller:”on occasion. He did not travel early, and he did not travel often” but he “gave comfort to democracy’s enemies, to decency’s enemies”.

Writing in 1943 George Orwell, the steady social democrat, considered: “Translated into political terms, Yeats’ tendency is Fascist. Throughout most of his life, and long before Fascism was ever heard of, he had had the outlook of those who reach Fascism by the aristocratic route. He is a great hater of democracy, of the modern world, science, machinery, the concept of progress – above all, of the idea of human equality. Much of the imagery of his work is feudal, and it is clear that he was not altogether free from ordinary snobbishness. Later these tendencies took clearer shape and led him to “the exultant acceptance of authoritarianism as the only solution. Even violence and tyranny are not necessarily evil because the people, knowing not evil and good, would become perfectly acquiescent to tyranny. . . . Everything must come from the top. Nothing can come from the masses”.

Furthermore, Yeats “fails to see that the new authoritarian civilization will not be aristocratic. It will be ruled by anonymous millionaires, shiny bottomed bureaucrats and murdering gangsters”.

Orwell is generally unimpressed by Yeats’ poetry, and we hear similiar anti-Irish prejudices to those found in Auden’s work. He writes that “one seldom comes on six consecutive lines of his verse in which there is not an archaism or an affected turn of speech”. To an extent this criticism can be imputed to that writer’s affection for sparse, attenuated language which he spells out in his essay ‘The Politics of the English Language’. His attitude is encapsulated in his evaluation of one poem that: “It would probably have been deadlier if it had been neater”.

Nonetheless even Orwell swoons at some poems: “Yeats gets away with it, and if his straining after effect is often irritating, it can also produce phrases (“the chill, footless years”, “the mackerel-crowded seas”) which suddenly overwhelm one like a girl’s face seen across a room”.

Not surprisingly, Orwell lambasts Yeats’ occult dabbling: “As soon as we begin to read about the so-called system we are in the middle of a hocus-pocus of great wheels, gyres, cycles of the moon, reincarnation, disembodied spirits, astrology and what not”. These he links to reactionary leanings: if everything is indeed cyclical then the kind of society based on equality and democracy that Orwell prized was in some sense Sisyphean, a doomed effort”.

For any devotee of Yeats it is difficult to confront the fairly compelling body of evidence for this tendency, but as has been stressed these sympathies came at a time when the horror of Nazism was not apparent; when Communism might have seemed more contemptuous of human life and when the few remaining democracies were in the midst of the Great Depression. Yeats was wedded to archaic notions of aristocracy and fascism appeared to fit with his prescriptions. He failed to recognise the genocidal evil that lurked there.

Moreover, he was never implicated politically in any fascist movement. In fact the political campaigns that Yeats became involved in during his lifetime: the Irish Cultural Revival in the early 1900s and the campaign to retain divorce in the 1920s were progressive in character.

We find a flawed character in W.B. Yeats, like Orwell himself who informed on his former political brethren, but one who produced poetry perhaps unbettered in the English language in the twentieth century. None of it diminishes his greatness. We may bask in his words without subscribing to his political views.

Once a poem is written, the chord attaching it to the author is broken, and it assumes a life of its own. •