By Sinéad Pentony

The enjoyment of good health is unevenly distributed across Irish society. People living in deprived communities and on lower incomes experience poorer health and live shorter lives. Evidence is emerging of the negative impacts of New Austerity on the health and wellbeing of the population.

The differences in the experience of health among different sections of the population are known as ‘health inequalities’. Although some people will live longer, healthier lives due to genetic or hereditary factors, ‘health inequalities’ refer to inequalities which are unnecessary and unjust and avoidable, and can be addressed through public policies.

Our income, education, environment, work and life opportunities all have an impact on our health. All of these factors are interconnected and many of them are socially, politically and economically influenced. Government economic and social policies have a direct impact on people’s lives.

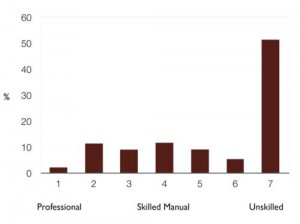

In 2010, the CSO published data from the 2006 census that clearly illustrated the relationship between life expectancy and where people live, and their social class. There is a six-year gap in life expectancy between professional and unskilled men, and a four-year gap for women (Chart 1). More recently, Census 2011 results on ‘self-reported’ health shows us the very high numbers of people in unskilled sectors reporting poor health (Chart 2).

The Institute of Public Health’s work on chronic diseases shows higher rates of coronary heart disease and diabetes among the most deprived fifth of the population compared to the rest.

Variations in life expectancy, health and social class raise issues of relevance to budgetary policy. Austerity is the medicine that has been used to restore the health of the economy, and five years on, the benefits of the treatment have failed to materialise.

It doesn’t work because it reduces growth, increases undemployment inequality and reduces the protection against personal economic shocks and bad health

Over the last five years we have experienced a sharp rise in unemployment, incomes have fallen and public services have seen significant cuts to their budgets, while at the same time being expected to deliver more with less. Poverty levels have risen, with almost one quarter (24.5%) of the population experiencing two or more types of ‘enforced poverty’, which covers essentials such as home heating, hot meals and adequate clothing. Almost one in every five children (18.8%) lives in a household experiencing relative income poverty.

Expenditure cuts affect those on low and middle incomes most. These cuts impose medium and long-term distributional costs to those least capable of bearing them. It is too early to see the impact of austerity in health statistics, but this doesn’t mean that the problems aren’t there.

The Simon Community, for example, has recorded significant growth in the numbers sleeping rough in Dublin city centre – a 66% increase in the first half of this year compared to the same period in 2012. When people lose their homes and live on the streets or in substandard housing, their health deteriorates.

New research into suicide has found that the 2008 global economic crisis may have led to almost 5,000 additional suicides across the world in 2009, including almost 100 in Ireland. Suicide charities report on the growing numbers of people using their services who are finding it hard to cope with the effects of the recession.

The latest results from the Growing Up in Ireland study show that a quarter of all three-year old children were overweight or obese. There was evidence of a social gradient emerging, with the least advantaged social class having the highest proportion of obese three-year-olds. The study also found that by three years of age children from the least-advantaged-social-class backgrounds were significantly less likely to be rated as very healthy compared with children from other class backgrounds.

While economic policies are not directly inducing illness, they are the “causes of the causes” of ill-health – the underlying factors that powerfully determine who will be exposed to the greatest health risks. David Stuckler and Sanjay Basu in The Body Economic, use evidence from 25 countries over many decades to show that austerity measures don’t work and have a detrimental effect on health.

They found that the real danger to public health is not recession but austerity. When social protection budgets are slashed, economic shocks like losing a job or a home can turn into a health crisis. A strong determinant of our health is the strength of our social-welfare programmes. When governments invest more in social protection – housing supports, unemployment benefits, pensions and healthcare – health improves. This is a cause-and-effect relathionship seen across the world.

They argue that austerity has failed because it is an economic ideology, that is not supported by data, which stems from the belief that small government and free markets are always better than state intervention. Stuckler and Basu’s analysis demonstrates how austerity has choked off economic growth and deepened recessions.

They found that governments that have increased public-sector spending have seen faster economic recoveries, which in turn helps them to grow out of debt. But the greatest tragedy of austerity is not that it has hurt economies, but the unnecessary human suffering that austerity has caused.

Public spending in areas such as health, education and active labour market programmes have a critical role to play in boosting economic growth and improving public health. Health and education have large fiscal multipliers, typically greater than three, which means that every euro of government spending contributes an estimated three euro in future economic growth.

‘While economic policies are not directly inducing illness, they are the “causes of the causes” of ill-health’

Ireland’s public-spending ratio in GDP terms is average by EU standards and there remains a substantial deficit in the public finances. However, our tax take was the sixth lowest in the EU in 2011, which means (at a minimum) there is scope to protect existing levels of public spending and address the deficit through taxation.

Social and economic policies have collateral effects on health and we need to know the full consequences of our policy choices on the health of the population. All public policies should be evaluated for their impact on health and health inequalities. Avoidable health inequalities are wrong, and if we can make policy decisions that reduce health inequalities, this in turn will create a better and fairer society for all.