One does not wish to speak ill of the recently dead but one cannot help seeing the death of Peter Sutherland as symbolic of a change of mood globally about globalisation. Globalisation, which as an ideology means essentially uncontrolled free movement of capital, has gone too far. It is now a major threat to State sovereignty and to democracy and therefore to the lives and prosperity of millions of people who are not fortunate to be in the fast lane.

John Bruton said on radio that what he admired about “Suds” was his ability to resist political pressure. Another way of putting that is to say Sutherland had contempt for democracy. He was one of the most powerful international figures of the last forty years but was never elected to anything. His failed encounter with the voters of Dublin South East as a young Fine Gael Dáil aspirant scarcely made him an enthusiast for elective democracy.

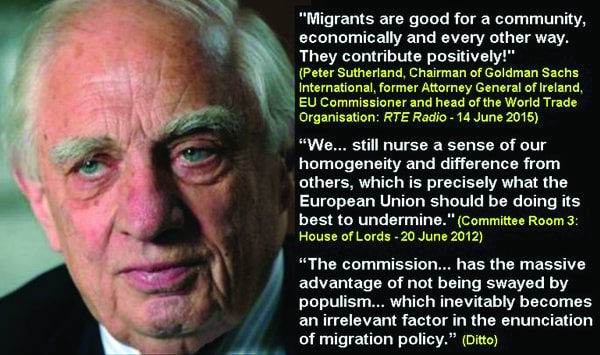

His obituarists praised the nobility of his work of recent years on international migration, which he undertook on behalf of the UN and the Vatican. Yet in June 2012 he made the following extraordinary statement to the Committee on Migration of the British House of Lords: “The United States, or Australia and New Zealand, are migrant societies and therefore they accommodate more readily those from other backgrounds than we do ourselves, who still nurse a sense of our homogeneity and difference from others. And that’s precisely what the European Union, in my view, should be doing its best to undermine”.

So in this sphere of his many-sided activity the intensely political Peter Sutherland was driven not just by humanitarianism but by a frankly admitted desire to undermine the cohesion of Europe’s national communities – that being necessary to advance the EU “cause” of which he was a fervent lifelong advocate.

Fintan O’Toole in the Irish Times roused the ire of some of Sutherland’s admirers when he wrote that no one personified quite as clearly as he did the two sides of neoliberal globalisation, “its phenomenal energy and its terrible destructiveness”. Quoting John Bruton’s remark that ”Taming nativist and nationalist trends was a daily battle of Peter’s life”, O’Toole wrote insightfully:

“If so, it is is a battle he can hardly be said to have won. The nativist uprisings that now threaten the very existence of liberal democracy are not mere reactions to the kind of globalisation that Sutherland did so much to drive forward. They are products of it. If, as he did, you tie globalisation to a feral form of finance capitalism, you build into it the gross inequalities and the profound instabilities that undermine the democratic bargain. Much as he was disgusted by them, there is a sense in which Donald Trump, Brexit, Viktor Orban and Marine Le Pen are part of his legacy too”.

That is a fair summing-up of Peter Sutherland’s legacy by one of Ireland’s leading intellectuals, but what is the democratic bargain that Fintan O’Toole refers to? He counterposes globalisation and feral finance capitalism on the one hand with “nativism” and “nationalism” on the other. He sees both as threats to “liberal democracy”. But what is that? Implicitly he seems to regard democracy as a matter of fairer income distribution and the elimination of “gross inequalities”. But is that an adequate definition?

The paradox is that Peter Sutherland was, as Fintan O’ Toole very much is, a fervent supporter of the EU integration project and supranationalism, although perhaps for different subjective reasons.

Yet the opposite of ideological globalisation is not nativism, nationalism and populism, but national democracy.

National democracy is the only stable basis of modern States. And Fintan has remarkably little to say about it, even though it is an issue that is fundamental to the debate on the EU.

The trouble is that he does not understand the national question.

Fintan O’Toole is a New Statesman leftwinger whose radicalism encompasses all the liberal causes. There must be minimum public interference with the life-style choices of individuals. Tolerance is the highest value. His heart is in the right place when it comes to the misdeeds of Church and State, the ravages of feral finance, the exploitation of the undeveloped world, global warming and the rest. But his blind-spot is the EU, which is why he shares Peter Sutherland’s and John Bruton’s denigration of the opposition to supranational integration that is now growing across Europe as ”nativism”, “populism” and “right-wing”.

He does not see this for what it really is: a manifestation of the basic and understandable democratic desire of the peoples of Europe to make their own laws through the public representatives they elect and to win back control of the State powers their national elites have handed over to Brussels during the past sixty years.

The ABC of the national question is straightforward enough. Once mankind has passed beyond the clantribal stage of society in which political relations were based on kinship, the human race finds itself divided into nations. The right of nations to self-determination was first proclaimed in the Declaration of the Rights of Man of the 1789 French Revolution. That right is proclaimed again in the UN Charter and is a basic principle of modern international law. It is a collective human right and attaches to individuals as members of their national collectivity.

Abraham Lincoln said at Gettysburg that democracy is “Government of the People, by the People, for the People”. But who are the People? The People is the ‘demos’, the political community where there is sufficient mutual identification, commonality of interest and natural solidarity between its members to induce minorities willingly to obey majority rule because it is ‘their’ majority and they identify with it for that reason. A ‘demos’ is a collective ‘We’. In Nation States this is primarily an ethnically-based community where people share a common language and national culture. In multinational States it is a civic community, a community of citizens, where people are still willing freely to obey majority rule because they identify with that as rule by ‘their’ majority. But for Multinational States to be stable and endure the more populous nationalities within them need to be especially solicitous of the national interests and identities of the smaller nationalities.

The EU on the other hand is the opposite of a democracy and can never be democratised because there is no such thing as a European ‘demos’. There is no pan-European community of people who are willing to obey majority rule because they identify with and give legitimacy to that as ‘Europeans’. National identity, which is natural, organic, spontaneous and bottom-up, will always trump bureaucratic attempts to create an artificial “European” identity by various top-down schemes and devices. A European identity can be no more meaningful politically than an African identity, an Asiatic one or a Latin American one.

When asked in the 1950s what he thought of the French Revolution Chinese Foreign Minister Chou-en-Lai said that it was too early to say. The national question, the aspiration of new nations to have their own State and of old nations to take back control of making their own laws from the forces of globalisation is nowadays asserting itself all around us.

Since World War II the number of States in the world has gone from some 60 to nearly 200. At their present rate of disappearance the 6000 or so different languages in the world will fall to some 600 during this century, in each case spoken by at least one million people, in some cases by many millions. Clearly there will be many new nations endowed with the democratic right to national self-determination that will aspire to independent statehood. The international community will probably end up with 400 or more States.

Peter Sutherland opposed these democratic principles all his life. Fintan O’Toole has not yet grasped them. It is the core weakness of his political analysis.