How church and state kept the Life of Brian from a god-fearing society – Michael Mary Murphy

Thirty years ago this month on an Air Canada flight to Toronto, John Cleese turned to other members of Monty Python and said “I want out”. He felt they’d lost their originality. Though ‘Monty Python’s Flying Circus’ never flew again, it had made some social downdrafts on a trajectory towards radical, politically-progressive comedy since its inaugural takeoff in 1969. At the beginning of the 1980s the circus came to Ireland.

When you wonder how far we’ve come it is useful to go back and see how things worked in the old days. Just what is permissible in a society. And who determines it.

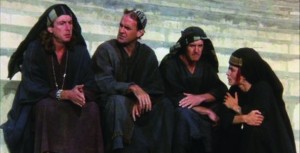

In August 1980 the Irish media began to carry reports of ‘The Life of Brian’ made by the Monty Python comedy team. Especially when Christ is being crucified for amusement, one person’s funny bone may be another person’s sore spot. When the sacred and the profane collide, fault-lines in society are revealed. Looking back at this curious case, we can learn a lot about how Irish society functioned a generation ago.

Showband priest Fr Brian D’Arcy warned: “Anybody who buys this and finds it funny must have something wrong with their mentality”

Brian was creating controversy in that bastion of liberalism, the United States, where it was first released. And where you have controversy, you have moral entrepreneurs. The Irish Times carried an AP wire story which made two important points: the film outraged religious leaders and it was thriving at the box office in New York. The Irish Times as well as the Irish Independent, and even the Anglo Celt, found space to inform their readers that the film had opened and closed – on the same day – at the Mall Cinema in Columbia, Maryland. This venue was not normally scrutinised by Ireland’s cultural commentators.

By January 1981 the Irish Independent’s front page blasted a story concerning not the film, but the album of the soundtrack, featuring dialogue from the film as well as the blasphemous if musically-limited tune ‘Always look on the bright side of life’. This miserable little ditty later featured in the closing ceremony of the London Olympic games, without any walkout, even from the religiously aware.

The Indo based its story on the words of ‘showband priest’ Fr Brian D’Arcy. It included his caution: “Anybody who buys this record and finds it funny must have something wrong with their mentality”. The newspaper sternly reminded its law-abiding readership that the Irish Constitution “bans the publication or utterance of blasphemous or indecent material”.

The Indo kept the story on the front page the next day; now transformed into a debate on pornography. Cometh the headline; cometh the politician. Into the fray entered Fine Gael’s Michael Keating who was cited calling for “an urgent examination of the extent to which the laws we have on censorship are competent”. His worry was that records and video tapes were not covered by legislation. By Thursday the story still had legs: Under the headline Govt looks at defects in porn laws, the paper reported how “a group of concerned housewives from Naas, Co. Kildare” had popped in to the Minister for Justice to persuade him “to correct defects in the law, and establish some censorship agency…”

The paper also reported that an authoritative-sounding ‘Christian’ group, “the Legal Consultative Council” was investigating methods by which they could make the unreleased ‘Life of Brian’ the subject of criminal proceedings. John Cleese flew – without his circus or any price-reducing competition on the route – to Ireland to defend the film on RTé’s Week Out programme. It is tempting to imagine him, Basil Fawlty-like thrashing a willow sapling against the desk screeching “It is not blasphemy, and even if it was, it’s bloody funny”.

Before the weekend, the Irish Independent had good news for middle Ireland. The soundtrack album was being withdrawn. Fearing the potential legal implications of handling an album that had sold ‘a few hundred copies’ without remark over a period of months, the compliant firm simply stopped selling it. Presumably the ‘concerned housewives from Naas’ could return to being unconcerned, and life would return to normal. Fr Brian D’Arcy was again quoted: the album is “a mockery of God’s word and is blasphemous”. Later Fr D’Arcy would himself brave the wrath of his church’s congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith with some God-depreciating views of his own, but that’s a detour. The Indo mentioned how the record’s distributor Solomon & Peres had received “complaints and threats” over the matter. The Irish Press noted Solomon & Peres had “been inundated with complaints about the nature of the record” and the Irish Times quoted a crestfallen spokesman who agreed that “a lot” of calls had been made, but noted that “only about three or four” appeared to have heard the record. The paper-of-record quoted a gnomic Fr D’Arcy on the resolution of this cultural skirmish: “I’m not one for censorship. It was entirely their [Solomon & Peres’] decision, and I would say they acted responsibly, but in the end the good taste of the public would have decided the issue”. The Times reported Solomon & Peres: “one woman actually threatened to burn down our premises unless we withdrew it”. It was later reported that the firm had received “a dose of threatening phone calls promising to beat up members of the staff – and worse”. Good taste, it appeared, was being reinforced by the availability of real physical clout.

One of the most incendiary aspects of the case is the equation of comedy with mental health problems. D’Arcy was not alone in declaring anyone enjoying the film or record as having “something wrong with their mentality”. The brothers of St John of God, charged with administering mental healthcare around Ireland also equated ‘The Life of Brian’ with pornography. Their magazine, Caritas, bemoaned an “endless stream of soft porn”, “much of it specifically aimed at children by large British corporations…damaging to the long-term mental and spiritual health of teenagers.” History does not record precisely what the magazine was referring to.

Understandably anxious to ground the story it had manufactured via its headlines in a global context, the Indo reported how a ‘Life of Brian’ book had been banned elsewhere. The South African Directorate of Publication had placed it in a list of prohibited works. Also included was a recent book by John McGahern.

Less God-fearingly, the London Evening News reprinted the Indo’s Brian-denouncing front page. In this era the populist English media didn’t like to pass up any opportunity to demean the Irish. Their headline read Begorrah, What a Life! We couldn’t even live in a country that banned records without being represented as thick.

Naturally when the film was scheduled for release it was banned by censor, Frank Hall. Another film, Richard Gere’s ‘American Gigolo’ was also forbidden. Appeals were lodged with the censors, and Gigolo was allowed in. But not Brian. Although it did go to the places where unsuitable cultural products end up: pubs and Universities. Fancy new video cassettes allowed publicans and College societies to exhibit films, albeit generally illegally and in contravention of copyright laws. And some commentators spoke up against the censorship. Both Ciaran Carty and Des Hickey in the Sunday Indo stood against the mob and sided with the film. In the same paper, playwright and columnist Hugh Leonard, while declaring himself no fan of the film, described Monty Python as “a grass snake, not the Biblical serpent”.

Yet one of the most salient opinion pieces of the time came from the unhysterical Meath Chronicle which wondered why ‘The Life of Brian’ was banned in Navan (except in one local pub) when the Lyric Cinema was projecting ‘The Blood Splattered Bride’. This Spanish exploitative bloody-nightdress-fest – with lesbian-vampire-action – drew an approving nod from the Irish censor. ‘The Blood Splattered Bride’ was also exhibited in Donegal’s luxury cinema on the weekend of March 19th and 20th before being replaced by a documentary on the life of the Pope.

And where was I, as the cultural battle raged in the kitchen, the minds of the depraved, the media, the church, the cinema and even the pub? Which side did I take? I faced a stark choice. Side with the Naas concerned housewives or with mental defectives. I took the cowardly option. I moved against both. But here’s the ethically-ingenious bit: I busied myself entrepreneurially providing home-made cassette copies of the album to eager schoolmates, so raising a flag for modernity while depriving heathen music-makers of a portion of their profits.

I thus advanced my finances in those frugal times without prejudicing my young soul and sure enough, within four years Monty Python and his godless flying spectacle were gone.