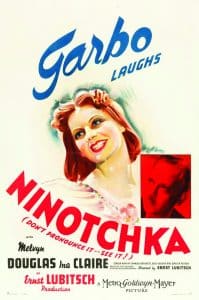

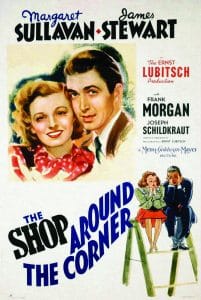

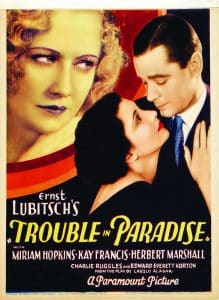

The last day of November this year marked the seventieth anniversary of the death of Ernst Lubitsch, whose greatest works, such as ‘Ninotchka’, ‘To Be or Not to Be’, ‘The Shop Around the Corner’ and ‘Heaven Can Wait’, are now widely unknown. Lubitsch himself, who started his career in silent movies in his native Germany and ended it as one of Hollywood’s most prestigious producer-director-writers, is certainly now an obscurity. But the list of stars who benefited from the once-famous ‘Lubitsch touch’ contains many familiar names: Greta Garbo, Betty Grable, Mary Pickford, Marlene Dietrich, Jack Benny, Maurice Chevalier.

That list deserves a little consideration, as it tells us something about the nature of celebrity. Regardless of the age of the reader, it is reasonable to think that most of the names there are familiar, and yet it is also reasonable to assume that very little specific is known about any of them. At best, most readers will have a fair idea of what Dietrich or Garbo looked like, but does anyone watch films with these actors in them, anymore?

The first centenary of cinema was celebrated around 1995, but in fact for the first 20 years or so, almost all moving pictures were non-fiction recordings of street life that were viewed as much as a funfair attraction as anything else. So really what we regard now as cinema, that hugely transformative, mass cultural development, has only just turned 100. In its short existence, it pumped out thousands of films that were consumed as intimately shared experiences, that drew millions of people into a vast simultaneous sensorium, the like of which was only dimly prefigured by mass newspapers and radio.

Because of this technological wonder, people from across the world were able to swoon for the same actor, who appeared to every single one of them in the same way. The star system was born, pre-eminently in Hollywood, but also in other national cinemas. That system carried on more or less intact right through cinema’s first 50 years or so, when there was relative scarcity of screen experiences for most people.

So for quite some time, viewers had to passively wait until a new film appeared, which they could then dutifully go and see. The widespread adoption of television in the 1960s and 1970s began to change things somewhat, but it was not until the spread of video in the early 1980s that viewers began to have any control over what they could watch.

Once the back catalogues started to come out in all the various formats that have cascaded since those developments, we left the era of scarcity behind. There was a brief period, perhaps 1980-2000, of what may be called an era of plenty. And now we are in the era of glut.

This goes some way towards explaining why those old Lubitsch films don’t get watched anymore. The dizzying array of offerings and hundreds of hours of content mean that there are very few simultaneously experienced screen moments anymore. They do still happen in the cinema itself, assuming nobody in the theatre has watched a ripped version in advance. And sports broadcasting still provides some shared moments, though of course recordable television has made it increasingly common for fans to save a match for viewing at their convenience, while trying to avoid the social media simultaneity of their friends reacting to the live results.

In short, there are no longer very many shared touchstones of screen culture, such as those Lubitsch films, which once would have been justifiably called ‘classics’ and now are in an uncertain zone between ‘obscure’ and ‘cult’.

The tense of the verbs that we use to talk about media have undergone a corresponding shift. No longer do children in the schoolyard or colleagues at work ask ‘Did you see Top of the Pops last night?’ Now we ask ‘Are you watching ‘Game of Thrones’?’, or ‘What season are you on now?’, or ‘Have you started watching ‘The Deuce’ yet?’. Viewing audiences, which for a brief 50 years or so were in a fixed lockstep of fandom, are now atomised and independent.

The realisation that we were all consuming precisely the same thing at precisely the same time was a great engine of social and artistic change. That weirdness of simultaneous experience is key to understanding Joyce’s ‘Ulysses’, for example. And it’s worth noting that the era of that book – set in 1904 and published in 1922 – spans those early years when the cinema as mass entertainment found its feet (with no help from Joyce’s own entrepreneurial efforts at the short-lived Volta cinema on Mary Street, now occupied by Penney’s).

The risk that somebody would ‘ruin the ending’ of a film we had not seen was always present, most especially in the domestic television-viewing space. What used to happen far more often was that several generations would watch the same thing together, with the older ones having seen it before. This retreading of the viewing tyres for the older viewer transformed the favoured films (James Bond, ‘The Wizard of Oz’, ‘Some Like it Hot’) into a ritualistic, and sometimes wearisome and despised, experience. But the palpable tension of different sets of viewers engaged in the same thing, with the emotional energy in the room passing as much among the different kinds of viewers as between the screen and the viewers, are mostly things of the past now.

The newer phrase is ‘spoiler alert’, and we hear it all the time because of the way that no two people experience the same media timeline, with the exception maybe of X-Factor style phastamagorias, although viewers spend much of their time checking their phones for what viewers elsewhere think about the show on their phones. With more screens in the average home than people, there is no pressure or compulsion to watch the same things, and films that require a modicum of commitment to get into them, aka black and white movies, are neglected by younger viewers. Indeed, even media and film students need some persuading to endure these screen artefacts, and when they do, the verdict is usually excoriating. Not infrequently, a great number of viewers born since 1990 struggle to find interest in anything that is older than themselves.

What chance does Lubitsch have? If there is one time of the year when Lubitsch might be graced with our attention, it’s Christmas. That’s because the coming season is the last redoubt of the once-dominant regime of TV schedules, a system of organising filmwatching that many older viewers still rely on year-round. And because Christmas is for many people the only time of year that we sit and watch something together, occasionally the older generation will prevail upon the younger and oblige them to watch a black and white.

Lubitsch’s movies are the perfect type of filler used in the Christmas TV schedules (they’re old, so they’re cheap, and they’re sentimental). You will not have the patience or time to watch them at any other time of the year, and this is the only season when you can fend off attempts to grab the remote with claims that ‘It’s a classic!’. Christmas was invented in its modern form as a kind of ready-made nostalgia package, and so it is that the things we miss, or think we miss, are themselves subject to change.

So check your Christmas TV schedule, find out when a Lubitsch movie is on, and force somebody to watch it.

Cormac Deane lectures in film and media at the Institute of Art, Design and Technology