Ireland is known for its literature, but not for its science fiction. There is not a great number of Irish writers in the genre, but it is a puzzling fact that major international authors such as James White and Bob Shaw are barely known in their native Ireland. Science fiction often imagines alternative life-worlds, which give writers the chance to assess the present by composing thought experiments that explore the implications of a new technology, new social structures, or encounters with alien others. It might be a good idea, then, to look to Irish science fiction as a source of incisive critical comment on all aspects of Irish life.

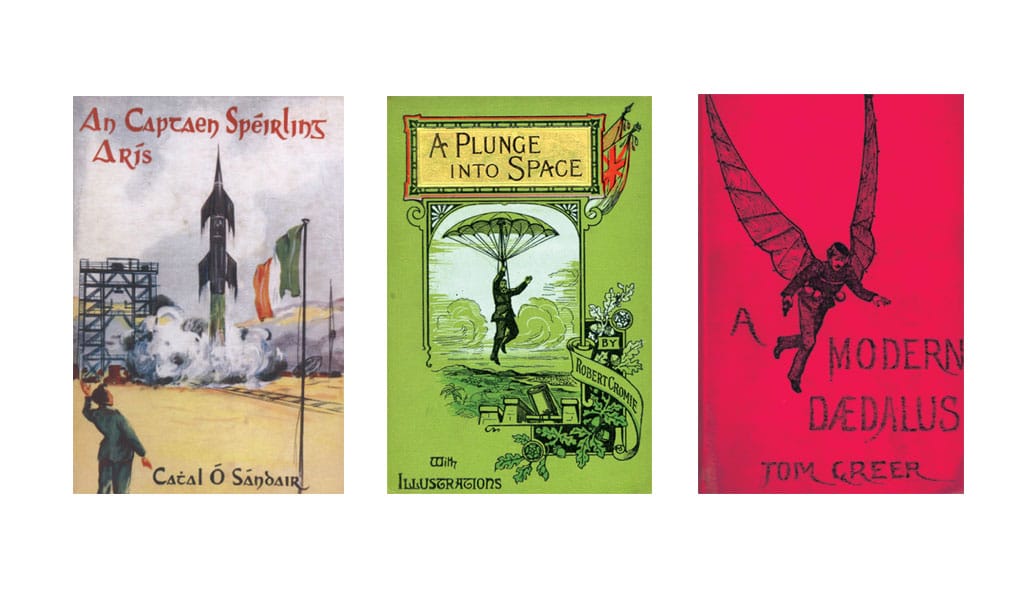

Fennell also uncovers science fiction in Irish. The four Captaen Spéirling novels by Cathal Ó Sándair were space-going adventures written in the early 1960s for children. Fennell points to the optimism engendered by an economic upturn in Ireland in the period as crucial for understanding the stories, with Spéirling described as “nothing more than a gaelgeoir Buck Rogers or Dan Dare”. Fennell also points to an imperialist theme throughout the Spéirling series, with the suggestion in the novels that Ireland’s history as a colony will ensure that aliens on any inhabited planets will be treated with the utmost respect when an Irish interplanetary imperialist project is established.

But O’Neill did have a passion for the science fiction of H.G. Wells. Upon publication of ‘Land Under England’, he sent the father of modern science fiction a copy of the book with a letter telling him that “‘Land Under England’ in so far as it has value, owes it to you more than to all other writers put together, because it is your works, the early ones as well as the later, that kindled my imagination to the point at which I felt that I wanted to create”.

‘Land Under England’ provides a fascinating inverse view of the newly independent Ireland. The novel details the adventures of a young Englishman who follows his father into a secret cavern beneath Hadrian’s Wall. His father’s obsession with the ancient Romans has led to the discovery of a hollow beneath the historic wall into which Roman civilisation has retreated. In their isolation, the Romans have evolved telepathic mind-control techniques in order to control their subjects and exist as a society of automatons. The novel is usually connected to the rise of fascism in Europe, but it also echoes events closer to home, in what Diarmaid Ferriter calls the “frenzied and paranoid” atmosphere of 1930s Ireland.

Indeed, after its publication, reviewers wondered whether its depiction of Roman automatons was a sly critique of Irish Taoiseach Éamon de Valera’s Fianna Fáil party, or his rivals in the fascist Blueshirts. In his role in the Department of Education, O’Neill was said to have been one of Archbishop McQuaid’s favourite civil servants, and O’Neill’s official writings on education and the church certainly bear this out. However, O’Neill’s final novel ‘The Black Shore’, published posthumously in 2000, reveals a more sardonic take on the relationship between church and State in Ireland, and perhaps adds a new dimension to the metaphorical significance of O’Neill’s Roman automatons.

Right, Slant Fanzine.

The bulk of Irish science-fiction literature has been produced by three Belfast writers: Bob Shaw and James White, who both wrote from the mid-twentieth century to its end, and Ian McDonald, whose career spans from 1989 to the present. Science fiction is a genre that tends to arrive with late modernity, so it is probably no surprise that a science-fiction tradition would take root in Belfast, given the history of industrialisation in the city. Bob Shaw and James White were friends who worked together at the Shorts aerospace company. White set up the Irish science-fiction group Irish Fandom in 1947 with his friend Walt Willis, with Shaw joining the group soon after. White and Willis met through the pages of the British speculative fiction magazine Fantasy, when White noticed a Belfast address in one of the letters to the editor and tracked Willis down. Irish Fandom was nominally a non-sectarian grouping, although White remained the only Catholic member throughout its existence. The group self-published the science-fiction fanzine Slant, which was printed using a hand-levered flatbed printing press. White made prints using woodcuts of rocket ships, astronauts and planets for the illustrations.

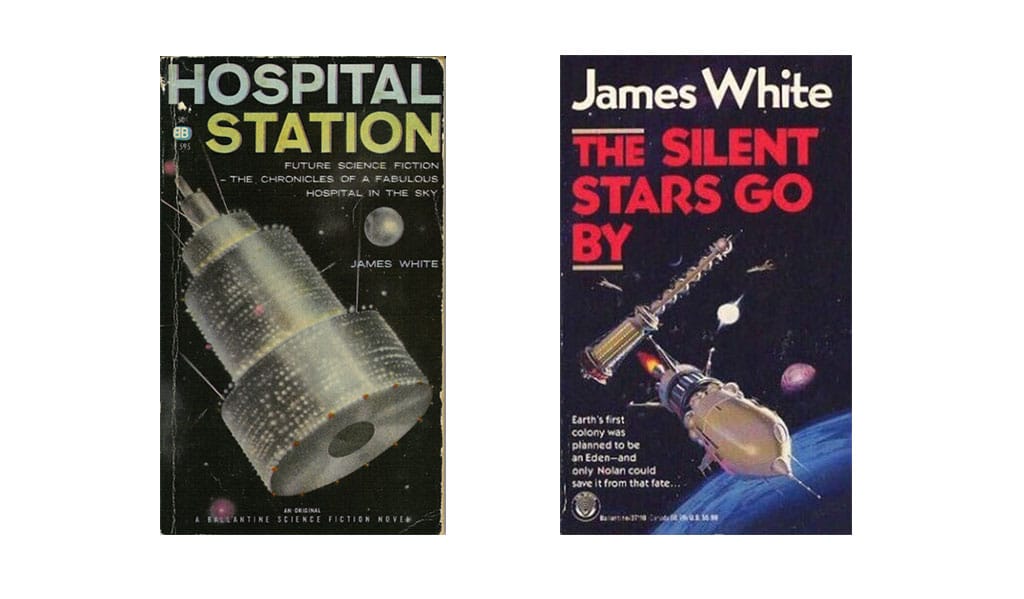

White saw his science fiction as an antidote to the violent and militaristic take on the genre that was internationally popular in the mid-twentieth century. His ‘Sector General’ stories depicted a vast space station that serves as a hospital for an assortment of alien species. These stories propose that the firmest foundation for contact between alien races is a medical encounter. Although White placed the first ‘Sector General’ story in New Worlds magazine in 1957, the context of the Troubles became increasingly relevant as the series carried on in numerous short stories and twelve novels, culminating in 1999’s ‘Double Contact’.

Although White was a self-declared pacifist, the vision expressed across the ‘Sector General’ novels is unlike the passive resistance of a Mahatma Gandhi or a Martin Luther King, which would have aligned with the burgeoning Civil Rights movement in the north. White’s pacifism was more of a top-down affair, with the Monitor Corps as the police force of the ‘Sector General’ universe guaranteeing peace with the threat of State violence. White’s standalone fiction is as interesting as his ‘Sector General’ stories, in particular his veiled Troubles commentaries ‘The Dream Millennium’ (1974) and ‘Underkill’ (1979). His final standalone novel ‘The Silent Stars Go By’ (1991) imagines a Hibernian Empire that has long since discovered steam power, which it uses to colonise a newly-discovered planet, with priests, bishops and cardinals dominating the mission.

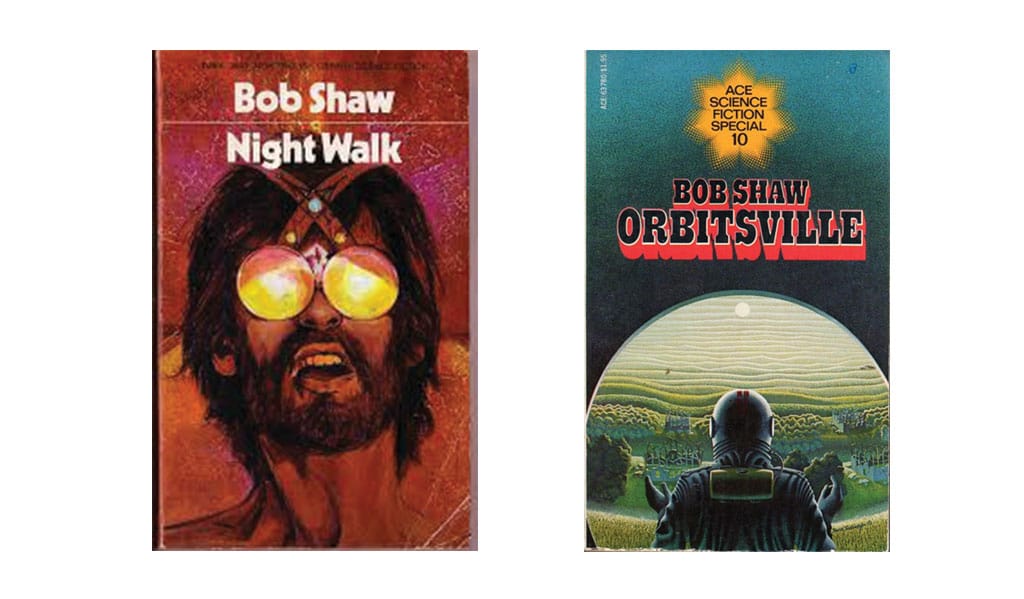

Bob Shaw is rather more cynical, his narratives undermining utopianism at every opportunity. His early fiction included ‘Light of Other Days’ (1966) and ‘Burden of Proof’ (1967), both of which were sold to the US science-fiction magazine Analog, overseen by the legendary editor John W. Campbell. The stories introduced the concept of slow glass, a substance that reduces the speed of light to an extent that events that take place in front of a sheet of slow glass are replayed later. The early ‘Slow Glass’ tales and the later novel ‘Other Days, Other Eyes’ (1972) propose many applications for the material: scenic views for urban dwellers, memorials of lost loved ones, spying, and crime detection. The latter is the theme of the story ‘Burden of Proof’, in which a judge waits to see whether the guilty verdict he gave in a murder case that sent the accused to the electric chair was correct, a pane of slow glass being present at the scene. Here and elsewhere, Shaw locates the tendencies in technology that undermine institutions and subvert our interpretations of history.

Shaw’s oeuvre covers a broad area of subgenres and themes within science fiction: time travel (‘The Two-Timers’, 1968), dystopia (‘The Shadow of Heaven’, 1969), anti-ageing technology (‘One Million Tomorrows’, 1970), nuclear cataclysm (‘Ground Zero Man’, 1971), and space opera (‘Orbitsville’, 1975, ‘Ship of Strangers’, 1978). His debut novel, ‘Night Walk’ (1967), touches most acutely on the sociopolitical climate of Belfast and the identities that flow around it. Depicting a future in which Earth has colonised other planets, the novel’s protagonist Tallon is a member of a group called the Block on the planet Emm Luther. The Block wishes to maintain a political link between Emm Luther and the home planet, engaging in acts of terrorism to further that cause. Tallon realises that the ‘flicker-transit’ technology with which space is explored has undermined the foundation of a planetary identity. He asks: ‘Why should a man choose one planet and say, this now I will put above all others? If he survived the psychic disembowelment of the flicker-transits and arrived on yet another miraculous green orb, why shouldn’t that be enough? Why carry with him the paraphernalia of political allegiances, doctrinal conflicts, imperialism, the Block?’.

Ian McDonald is from the cyberpunk generation, and his fiction features hacking, artificial intelligence and the link between spirituality and computer technology. His best received work is perhaps the 2004 novel ‘River of Gods’, set in a technologically advanced future India coming to terms with the effects of nanotechology and artificial intelligence. McDonald researched ‘River of Gods’ by spending an extended period in India and extrapolating from what he observed, a process he repeated in Brazil for 2007’s ‘Brasyl’, which revolves around quantum computing, and in Turkey for 2010’s ‘The Dervish House’, which explores the religious exploitation of nanotechnology. His latest novels, ‘Luna: New Moon’ (2015) and ‘Luna: Wolf Moon’ (2017) feature intrigues between the Australian, Ghanaian, Brazilian, Chinese and Russian families involved in colonising and developing the moon.

Inset, ‘River of Gods’ and ‘King of Morning’

McDonald has also written three Irish science-fiction novels, where he indulges his decidedly postcolonial take on the past and future of Ireland. ‘King of Morning’ (1991) examines Celtic Twilight faeries through the prism of alien invasion, ‘Hearts, Hands and Voices’ (1992) restages the War of Independence with nanotechnology and body modification, and ‘Sacrifice of Fools’ (1996) plants androgynous aliens in the heart of industrial Belfast and imagines the reactions of the locals.

So, could it be suggested that there is such a thing as an Irish science-fiction tradition? Before answering, it’s important to remember how genres are themselves constructed, and for particular purposes. The creation of science fiction itself was one such feat of imagination. In 1926 Hugo Gernsback cobbled the genre together by republishing Poe, Wells and Verne in his Amazing Stories magazine, and soon writers were making their own contributions and similar pulp publications began to thrive. Gernsback’s purpose was to provoke a young audience to think scientifically.

If we were to propose an Irish science-fiction tradition with a contemporary continuity, we could point to Louise O’Neill’s ‘Only Ever Yours’ (2014), Kevin Barry’s ‘City of Bohane’ (2011), and Mike McCormack’s ‘Notes From a Coma’ (2005) as recent examples. In addition, there are other works that could be appraised through a science fiction lens. The science-fictional tendency of Samuel Beckett’s ‘Endgame’ (1957) has already been explored by the critic Carl Freedman, and Francis Stuart’s ‘Pigeon Irish’ (1932), ‘Faillandia’ (1985) and ‘The Abandoned Snail Shell’ (1987) are also texts that might reward assessment as examples of an Irish science-fiction sensibility, albeit a muted one.

What would be the benefit of arguing that there is such a subgenre as Irish science fiction? Well, possibly it would be a useful way to identify where critical thinking is happening in our society. Critical thinking is not the same thing as creativity or innovation, terms that have been swallowed up by post-2008 neoliberal recession discourse. Critical thinking is stymied when the ownership of media outlets (press, radio, TV, online, advertising) is owned and controlled by ever smaller cliques. It is also stymied by the ‘doing more with less’ ethos of public sector reform, which encourages groupthink and discourages independence in education, health and the public service generally. Science fiction is the ideal genre with which to critically reflect on the present and imagine alternative life-worlds. An Irish science fiction would be part of that project.

Richard Howard is a lecturer whose PhD research at Trinity College on Bob Shaw and James White was funded by the Irish Research Council.

This article was commissioned for Village Magazine by Field Day. Founded in 1980, Field Day is a publishing and theatre company dedicated to cultural critique. A Field Day podcast will be launched later in 2017.

This article was commissioned for Village Magazine by Field Day. Founded in 1980, Field Day is a publishing and theatre company dedicated to cultural critique. A Field Day podcast will be launched later in 2017.

www.fieldday.ie