It’s perhaps something of an understatement to say Eoghan Murphy is not exactly flavour of the month these days. Not only is he facing public ire over the homeless crisis, but some political pundits are even going as far as to claim he has been the worst Minister for Housing, Planning and Local Government in the past 20 years.

It’s perhaps something of an understatement to say Eoghan Murphy is not exactly flavour of the month these days. Not only is he facing public ire over the homeless crisis, but some political pundits are even going as far as to claim he has been the worst Minister for Housing, Planning and Local Government in the past 20 years.

It’s also certainly not an exaggeration to describe Village magazine as one of his most vocal detractors since he took over the portfolio in the summer of 2017. But regardless of whether or not you agree or disagree with his policies, it’s a measure of the man’s character that he readily agreed to sit down for this in-depth interview while other senior politicians in the firing line wouldn’t have even bothered picking up the phone.

If nothing else, he deserves credit for exuding grace under pressure.

Jason O’Toole: Were you always a Fine Gael-er?

Eoghan Murphy: No, I wasn’t. I don’t come from a Fine Gael family. We were interested in politics. We discussed it as a family. It wasn’t until I was 26 – and I was living and working abroad and things were starting to decline here – that I thought about coming home and getting involved in politics. I was working in policy in Vienna and I was writing speeches for the head of the organisation there. And as I thought about it, I met Enda Kenny by chance in London and he was quite influential in terms of persuading me to get involved in politics.

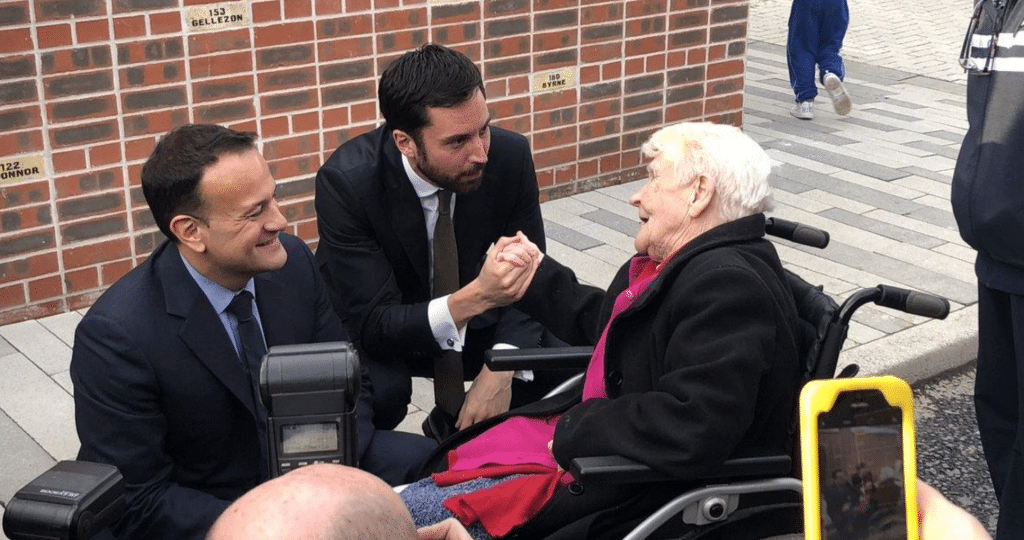

You’re now a close confidant of Kenny’s successor, Leo Varadkar.

Certainly, as we worked through the campaign planning, we developed a stronger rapport. He’s also big on honesty. If you’re honest with him, he will respond in kind. During the leadership campaign we became more personally close as you do when you’re working long hours directly with someone, but it’s difficult now with such busy jobs to find time to talk about things that aren’t work, but we try. He knows my family and there isn’t much he wouldn’t know about me. First and foremost, he’s the Taoiseach and I’m the Housing Minister, and we will step out of that relationship only on occasion. Like at Tom and Jen’s wedding recently. That was great fun, we were both just there as friends of the bride and groom and so we were able to relax a bit.

Some tabloids recently took an interest in your personal life after you were photographed at TD Tom Neville’s wedding with your date. It must be very uncomfortable to open up a paper on a Sunday morning and see speculation about your love life?

I don’t pay any attention to it. My focus is on my job. When I get time to myself, which is rare, I like to spend it with friends and family, go for a run, that type of thing.

Is politics like a drug for you?

It’s not a drug for me, no. But it is a vocation. I didn’t expect that when I first became involved –that it would end up consuming all my time and energy. I didn’t think I could get any busier as junior Finance Minister but Housing is another level altogether. And it’s not just Housing – planning, local government, water, emergency weather management. It’s very personal for me because it’s been my daily life for more than two years now. And people don’t really make a distinction between you and your job –you just are the Housing Minister, Saturday night, Christmas Eve, whenever. That’s not a complaint. Even if people weren’t like that I don’t think it could be any other way for me. Elections and campaigns and that side of politics is different though, maybe a bit more like what you’re asking. I’m very into that. The strategy, the execution. Whenever I go places, be it Ardee or Ballina, I want to know what’s happening on the ground, how the party stands, who is up-and-coming, what’s the competition like. That’s the bloodsport side of politics and it’s kind of addictive, even though that’s not why I’m in it.

Would you like to be Taoiseach some day?

It would be a real honour certainly. But when I took this job I said it would likely be the most important one I would have in public life, and I believe that. That’s still my ambition. I don’t have one eye on another Department or on the leadership of my own party. I intend on fixing the crisis in housing – that’s my ambition.

When will we see an election?

I don’t know. I don’t think it will be until the middle of next year at the earliest. The Taoiseach’s been very clear that he doesn’t foresee the need for an election before the summer of 2020. I think Micheál Martin has almost agreed to that.

Do you think a Fine Gael/Fianna Fáil coalition could work?

I think the current coalition is working very well, y’know. We’ve had to handle some difficult situations – Brexit being one, which is ongoing –and we are doing that as a minority government when many thought minority government couldn’t work. I’ve huge time for Finian McGrath and all of my independent colleagues and the contribution they make to government is significant. If in the future coalition with Fianna Fáil had to work then it would and I’d go with that, but I think everyone’s focus is very much on doing the job now, and continuing as an effective government in to next year and possibly longer. Because obviously we still have a lot of work to do and plans to see through.

In the past, the so-called poisoned chalice for politicians used to be the Department of Health but it feels like it’s your Department these days.

I think anyone who might come into politics and look at a Department and see it as a poisoned chalice shouldn’t be in politics. I got into politics because I want to ultimately help people.

How do you respond to detractors who say you are not the right man for this portfolio because you come from a privileged background and are out of touch?

Well, that’s just a load of nonsense. But it’s also disappointing in a way because it’s a real Trump tactic that we are seeing more and more of in Ireland –make nonsense allegations about an opponent to distract from your own policy shortcomings. Absolutely criticise the policy, no problem. Let’s debate it. But the fact is the opposition have supported 99% of what we are doing, as have NGOs and others. We can’t do much without their approval because we are a minority government. If they want to change things they can: they are the majority, they have more votes. But they haven’t come up with significant or alternative policies –some tweaks to what we are doing, sure, which get taken on board because that’s our approach as a government. It has to be. If it wasn’t though I would still operate that way because I was one of the main advocates for political reform in the last Dáil; I believe in a collaborative legislative process. That gets better results for everyone. But on housing, the opposition haven’t proposed any major alternative proposals. Instead, they reduce the whole debate to name calling – and housing is just way too important for that.

So, you’re saying you’re up to the job?

Yes. And this government is up to the job.

You got into some considerable controversy over your description of co-living.

I put my foot in my mouth! Co-living isn’t the solution to the housing crisis, but nor is it the problem. It has a role but a very small role for a cohort of people. Our focus is building apartments and housing because that’s what we need to do for people living and working here.

Sinn Féin now wants to ban co-living…

The debate around housing issues can get hijacked from time to time. It’s such an important issue and yet, occasionally, the opposition try to distract people from what’s really going on. Co-living is a good example of that. We will build 20,000 new homes and apartments this year – none of them co-living. Co-living will work for a very, very small cohort of people, none of them vulnerable, freeing up much needed accommodation elsewhere. And yet the Dáil will come back in three weeks time and already SinnFéin are laying the ground work to pull a stunt on it and try and ban it. We will spend all this time debating it when our focus should be on the essential issues around supply and tackling housing insecurity and affordability issues. Last year they came back after the summer break and put down a motion of no confidence in me, because I hadn’t solved the crisis in one year. This year they will try and ban co-living before it has even had a chance. It’s cheap PR stunt stuff and they continue with it despite the seriousness of the crisis and in spite of the fact that the electorate have flatly rejected this kind of approach. They lost in a big way in the locals and Europeans, particularly in areas where the housing challenge is most acute.

The homeless crisis seems to be getting progressively worse year on year. What’s being done about it?

It’s an incredibly complex challenge. What we’ve seen so far this year, as a result of a lot of the work that we have done, is some important progress. For example, for every two families that would’ve presented (themselves) to homeless services so far this year we found a home for one of those families immediately – they haven’t had to go into emergency accommodation. But for the last three months we’ve seen the number of families and children in emergency accommodation falling and there’s now less children and families in emergency accommodation than there was this time last year. We’ve also seen a reduction in people rough sleeping. But there’s still more than 10,000 people in emergency accommodation, which is unacceptable. Over the last three years we’ve helped more than 77,000 people into homes. But clearly we need to do more. One in four homes we built last year was for social housing – we haven’t done that in years. And that’s how you help people who are homeless – you build homes so they can go into those homes. Also, I set up an inter-agency group for homelessness to co-ordinate all of our actions at government level because it’s not just about housing and shelters – it’s also about social justice issues, it’s about health issues, it’s about immigration issues.

Have you ever found it hard emotionally, knowing there is so much misery behind all those stats on your desk about homelessness?

I think about, meet and speak to, people affected by the housing crisis every single day. It can be an incredibly emotional period in people’s lives and the buck stops with me. Yes, I do find that end of it difficult but it’s immaterial when you put it beside what those in crisis are living through. I do get invited to new homes when people are moving in and I’ve now met many, many people who have left emergency accommodation (and moved) into their own home. It’s emotional stuff. To hear their stories, to witness their lives changing, improving. And when I visit Emergency Accommodation it makes me even more determined to make sure that everybody gets the home they need. Like I said, we now have less families in emergency accommodation than this time last year. 10,000 families will get new social homes this year. But there’s still much more to do.

Can you see why people might think Fine Gael is practically on the side of developers who fund it and homeowners who vote for it (and are thriving economically on the high prices and high rents) and so practically and ideologically against the outsiders who have no housing but would be unlikely ever to vote for Fine Gael?

I don’t see that. I have said countless time since I first came into the job, in fact, that ideology was not going to stand in the way in terms of us delivering the solutions that people need. I’ve also said on a number of occasions that the market is not going to solve this crisis, it never has – only the government can. And that’s why we have set forward –and we’ve taken back responsibility for social housing, which other parties outsourced almost exclusively to the private sector – so that one in four of all the houses built last year was for social housing. We’ve also got the new land development agency, which is going to have a very important impact in terms of land pricing and land availability.

Also, if you look at what’s happening in other countries and you look at some of the thinking that used to prevail, the idea that if you just built more homes that would bridge the affordability gap – that’s not the case. We haven’t seen that in other cities. So, if we want to make sure that people can afford to live in our cities and our towns then the government has to step in with affordability measures like the Help to Buy scheme, like the Rebuilding Ireland home loan and now bringing forward public land for more affordable housing. So, from that point of view, that’s what Fine Gael in government is trying to do with the support of our independent partners as well. We believe in home ownership, that’s why it’s so important what we’re doing about affordability, we believe that social housing has to be at the core of what a government does in housing policies –that’s why we now have that one-in-four to one-in-five new homes being built is social housing. And we also understand and believe that people in renting need to have greater security as renters and greater affordability as well.

Do you think there perhaps should be incentives for those people living in hotels in Dublin to relocate to other parts of country?

We are currently working on social housing reforms that will speak to that issue. First and foremost, though, if a family is in emergency accommodation in Dublin the best place for them to be, more than likely, is in the community, close to family, close to friends, where the kids are going to school. But there will be families –and I know this because we have met some –who would be open to relocating outside of Dublin. And that can be supported. We will be discussing that at cabinet level in September.

People on the social housing list can turn down the offer of a home three times. What about reducing this, to speed up the process?

There’s more than 70,000 people on our housing list waiting for a home. And that’s down about 20,000 over the last two-and-a-half years. And the difficulty is that when someone refuses a home it means the next person on the list has to wait that little bit longer. Now we’ve brought in some reforms like Choice Based Lettings, which is an easier way for people to navigate the systems themselves to find the right home for them. But one of the things that I have spoken about and I’ll be bringing it forward, with a series of sweeping proposals later in the year, is that where someone refuses a social housing home in their area of choice, if they do that twice, then they will go to the back of the queue, they will go to the bottom of the list, to allow other people waiting a chance to move into a home.

Why don’t you give the Airbnb regulation teeth so it might work?

I’ll talk about short-tem letting rather than talking about one particular company. What we have done in short-term letting goes further, I think, than any other city in the world today. We’ve effectively banned short-term letting in our cities and our large towns. And we’ve done that through the planning code because every local authority has a planning office and planning enforcement, and they’re best placed to act on this. There is more that we can do. We can regulate short-term letting from a tourism point of view, in terms of regulating the platform and the providers. That responsibility doesn’t fall to me, but it’s not as important as what we have done this year, which is to get those short-term lets back into long-term use. Now the law has only just changed as of the 1stof July: there’s going to be a bedding down period but it is going to bring homes back into use for people who are living and working here, and I think that’s important. Also, people can still rent out a room in their house, or even their entire house when they’re going on holidays themselves. So I think we struck the right balance, but we’ve been very ambitious in terms of effectively shutting down short-term lettings in our cities and large towns.

Could the National Planning Frame (NPF) be made stronger by use of terms in the legislation like, “The NPF SHALL BE IMPLEMENTED by local authorities” and giving third parties the right to enforce them in court?

So, what we’ve done with the NPF is we have put it on a statutory footing, which didn’t happen before. So, it is as strong in law as it gets. And we’ve also now got an office of a planning regulator, which is a recommendation from the Mahon Tribunal to make sure that the NPF is implemented at regional and local authority level. So, the protections in law around our plan are very robust.

Is there any evidence the NPF is working? For example, has there been any shift whatsoever to development in Limerick and Waterford or against one-off housing and Dublin, since it was introduced? And I’m looking for stats (not anecdotes) which are all that count for the serious-minded.

The National Planning Framework came into effect, I think, in February of last year. It’s a 20-year vision for how we should plan the future growth of the country. So, in one respect, it’s a little bit early to be looking for hard data, although there are a couple of things we can point to. So, for example, one of the funds under the National Planning Framework, one of the things we did for the first time was we matched our government funding with our planning –that hadn’t happened before. And one of those funding schemes is the Urban Regeneration (and Development) Fund to support regeneration. So, we allocated a significant amount of money at the end of last year for a number of projects and just recently, this week and last week, I was in place like Kilkenny and Wicklow where we where breaking ground on some of those projects.

But another thing which is interesting as well, if you look at planning permissions you’ll see that increase in planning permissions for one-off houses is in the single-digit growth. I think it’s less than 5 percent, but the increase in permissions for apartments is more than 50 percent. And so that would speak to a simple element of the National Planning Framework, which is more compact development in our urban areas.

But the other thing as well, just so you know, is you introduce the National Plan and then three regional assemblies make up the country in terms of the administration on the planning point, they then do their own regional plan that interpret the national plan and then every local authority has its own county and city plan. So, those regional plans are being finalised at the moment and when they are finalised things will start to move more quickly. But, like I said with my earlier point, we’re already seeing some evidence of it happening.

Why focus on increasing heights rather than densities?

We’ve done both. I’ve lived abroad and when I came into the housing portfolio I thought there was a strong opportunity for us to increase heights in our city centres. But it’s not just about skyscrapers, it’s actually about increasing the shoulder height, having a kind of default height level of, say, six storeys because that’s the best way to build a liveable and sustainable city. And when you look at all the investments that we made in Dublin in terms of education, healthcare, transport, public transport, there’s still a lot more we can get out of the city in terms of higher buildings and higher densities. And that’s why one of the first things I wanted to was to remove the height caps, and they’re gone.

You want to allow for taller buildings as well because it lends itself to good design but also (it means) developments having more than one use, which we see in other cities whereby there might be offices and apartments in a building and a supermarkets and something else.

Do you agree that the changes in height are resulting in speculation and the prolonging of prime vacant city sites, as applicants go back to see if they can increase the value of sites?

I think it was important to release the height caps in our cities so that we could increase densities and heights, so that we could get more people living in a more compact way. One of our big ambitions, through the National Building Framework, is to improve quality of life – so less time commuting, less carbon emissions through travelling, a stronger sense of community and taking advantage of the investments and infrastructure we’ve already made –and to do that I had to lift the heights cap. And so it was important in terms of planning for the next 20/40/100 years for this country that I do that.

Why did you reduce size and sun-orientation standards for apartments?

I thought we could do more to make sure that urban living and apartment living was attractive. So, making sure that we had proper bike storage and storage for apartments was an important thing, but also increasing the number of apartments per elevator shaft, I thought we should do more there. And then when we looked at things like apartment size –because we’re seeing more demand for one-bed and two-bed apartments –to make sure that when you were building a block you could include more one-bed and two-beds as well. We have to make sure we’re building more and more apartments.

Why does the planning regulator advise not regulate?

Well, he is the regulator and he does regulate – but the ultimate responsibility should fall to the Minister. So, he can order a review of what’s happening in a planning office or a local authority, he can order a review of what’s happening to the implementation of the National Planning Framework, he can look at individual cases, and then he can advise me… And they publish their advices so that people can see that advice and where I act on the advice, or if I don’t act on the advice, I have to bring that before the Oireachtas and explain why. But I think it’s important now that we do have this regulator – that they have all the powers that they need but ultimately when these decisions are made that they’re made by an office holder in terms of someone who’s politically responsible to Dáil Éireann.

Why have you sat on the Gerry Convie file (about corruption in Donegal planning) for nearly two years?

That’s a very important file and there has been a process on-going internally in the department since I came into the brief. And I can’t speak about it any further until I’ve had an opportunity to brief my colleagues at cabinet on it.

What have you done to assert the interests of the public where they conflict with those of developers?

I was on the city council when I first got involved in politics. At the time, the approach to development was developer-led planning. So, local authorities would engage with developers, see what sites they owned, what their ideas were, and from that bring recommendations to the Council to make decisions. But the National Planning Framework will turn things on its head. We now have planning-led development. We have said where we want development to happen in the interest of the public in terms of improving the quality of life, in terms of more sustainable communities, and it’s now for the developer to follow those plans. We’ve taken a very important (step) –it’s almost like a paradigm shift in planning –to move away from developer-led planning to planning-led development.

Could your legacy in Dublin City be one of low standards and lumpy high-rise?

Well, actually everything that we’ve done in relation to not just social housing but housing more generally has been to improve standards. So, again, if you look at the changes that I brought about into the rental sector just earlier this year, these are changes that are going to help improve the standards of private rented accommodation. We have been over the last two years reforming the different technical guidelines that we have for builders to make sure that they are building now to the best possible standards. And in social housing we are moving to nearly Zero Energy Buildings. So, we’ve actually been increasing standards as we’ve been increasing the number of homes being built and the types of homes being built.

![]()