See below : The Press Ombudsman has upheld part of a complaint that Village magazine breached the Code of Practice of the Press Council of Ireland. The complaint was made under Principle 1 (Truth and Accuracy) of the Code of Practice. Other parts of the complaint are not upheld.

Among the issues that have delayed the restoration of power-sharing government in the North is the failure of the DUP and the British government to honour previously-made agreements to deal with what are known as legacy issues. These include a promise to establish some form of historic truth commission to investigate the role of the British state and its security forces in the killing of hundreds of people during the conflict.

A documentary film, ‘No Stone Unturned’, examines the deaths of six Catholic men in the Heights bar in Loughinisland, County Down, in June 1994, just three months before the first IRA ceasefire in August 1994. The men were shot dead while watching the Republic of Ireland play Italy in the World Cup on 18 June, when two masked loyalists walked into the bar and one fired indiscriminately at the customers and staff.

Those murders were the subject of a 2016 report by the Police Ombudsman of Northern Ireland which found, following an earlier whitewash by the same office, evidence of Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) collusion in the protection of Loyalist paramilitary informants, who may have carried out the murders. While he found no evidence that the police knew in advance about the murder plot, the Ombudsman was heavily critical of how the RUC Special Branch handled informers, and failed robustly to disrupt the activities of UVF paramilitaries operating in south Down and to share intelligence with detectives investigating this UVF gang. He claimed there was a “hear no evil, see no evil, speak no evil” approach. The 160-page report by Dr Michael Maguire also found police informants at the most senior levels within loyalist paramilitary organisations were involved in the importation of guns and ammunition.

In the film, made by Oscar-winning director, Alex Gibney, three loyalists who were involved in the attack are identified, while it is claimed that the automatic rifle used was among a large consignment imported into the North with the knowledge of the RUC Special Branch and MI5 in the late 1980s.

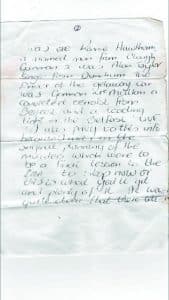

One of those named, Ronald Hawthorn, and his wife Hilary, were among those arrested following the massacre, but have never been charged, while another loyalist, Gorman McMullen, is named in the documentary as the getaway driver. A second attacker is also named and is believed to have left the North in the late 1990s and re-settled in England. The film claims that Hilary Hawthorn identified the gang members, including her husband, in two calls she made to an anonymous police phone line in the wake of the killings, and in an unsigned letter sent to a former SDLP councillor.

Her voice was recognised by police officers with whom Hilary Hawthorn worked in an RUC station, while in the anonymous letter she also claimed to have been involved in the planning of the attack. Ronald Hawthorn was arrested and questioned in August 1994, just weeks after the atrocity, while his wife was detained a year later. Neither was ever charged in connection with the killings. The documentary explains that Ronald Hawthorn was only named as ‘Person A’ by the Police Ombudsman, Dr Michael Maguire, who did not disclose the names of the three suspects, in a detailed and shocking report published in 2016. Another confidential and unpublished report prepared by Office of the Police Ombudsman of Northern Ireland (PONI) identified the suspects by name. It was subsequently sent anonymously by post to journalist Barry McCaffrey, who has spent years researching the Loughlinisland killings and who helped to make ‘No Stone Unturned’. The PSNI is currently investigating the leaking of this confidential document to McCaffrey.

The published PONI report by Dr Maguire sets out how the killings were carried out by the UVF which directed its members in Down and Antrim to organise attacks on nationalists following the killing of three of its members on the Shankill Road by the INLA in early June 1994. The Ombudsman concluded that there was collusion in the Loughinisland killings involving unnamed members of the RUC. He found that the VZ58 rifle used in the attack and subsequently used in a wide range of loyalist murders was part of a consignment imported from South Africa by police and MI5 informant, Brian Nelson, in late 1987 or early 1988.

Maguire wrote: “My conclusion is that the initial investigation into the murders at Loughinisland was characterised in too many instances by incompetence, indifference and neglect. This despite the assertions by the police that no stone would be left unturned to find the killers. My review of the police investigation has revealed significant failures in relation to the handling of suspects, exhibits, forensic strategy, crime scene management, house to house enquiries and investigative maintenance. The failure to conduct early intelligence-led arrests was particularly significant and seriously undermined the investigation into those responsible for the murders”.

During the attack, Maguire said, “one of the masked men crouched down, shouted ‘Fenian Bastards’ and opened fire indiscriminately with an automatic assault rifle. Both men then fled the scene in a waiting Triumph Acclaim car driven by an accomplice. The car was driven in the direction of Annacloy and found the next morning abandoned in a field on the Listooder Road between Crossgar and Ballynahinch. The car was destroyed while in possession of the police in 1995”.

The Ombudsman recorded how the families of the victims complained at the time that the vehicle should have been retained for potential future examination, especially in light of advances in forensic science. They state that police “wilfully destroyed” this exhibit, which they viewed as “wholly unsatisfactory and unreasonable”.

Dr Maguire said:

“In addition, investigative opportunities were undermined by the way in which information relating to those involved in the ownership chain of the car used in the Loughinisland attack was handled. The police also had intelligence that in August 1994 the murder suspects were warned – by a police officer – that they were going to be arrested. It is unacceptable that if such actions occurred, police failed to act on the information received and did not investigate this allegation further.

The investigation also identified the existence of intelligence sources within loyalist paramilitaries, who were not tasked effectively to obtain information on who committed the attack and to provide information that could further shape investigative action by the Murder Investigation Team. This was a ‘hear no evil, see no evil, speak no evil’ approach to the use of informants, which potentially frustrated the police investigation into the attack and restricted investigation opportunities and lines of inquiry.

I have found that Special Branch held intelligence that paramilitary informants were involved in a range of activities, including command and control of loyalist paramilitaries; the procurement, importation and distribution of weapons; murder; and conspiracy to murder. They have not been subject to any meaningful criminal investigation.

It is of particular concern that Special Branch continued to engage in a relationship with sources they identified in intelligence reporting as likely to have been involved at some level in the Loughinisland atrocity. If these individuals were culpable in the murders they took every opportunity to distance themselves by attributing various roles in the attack to other members of the UVF. The continued use of some informants who themselves were implicated in serious and ongoing criminality is extremely concerning”.

Among those killed in the Heights bar attack was Adrian Rogan, whose daughter Emma was elected earlier this year as a Sinn Féin MLA for south Down and who was due to celebrate her eight birthday just weeks after her father was killed. Following a private viewing in Belfast before the documentary went on general release, Emma Rogan said that it clearly vindicated the long-held view of the family and local nationalist community that “the truth about these murders was being covered up by the very people, the RUC, that were supposed to protect us.”. She called “for justice and accountability from those in authority”.

During the negotiations that produced the Stormont House Agreement in December 2014 the British government agreed to establish a mechanism to deal with these and other outstanding legacy issues but little or no advance has been made on the commitment. The Loughlinisland attack is not the only one about which the families of those killed or injured are seeking the truth. It is an issue that concerns many thousands of people who have been affected by State-related killings during the conflict. There are many in the unionist and loyalist communities who are equally frustrated at their inability to establish the circumstances surrounding the deaths of their loved ones caused by republicans or by police informers within the loyalist organisations.

The most high-profile case in this regard collapsed last month when the North’s Public Prosecution Service decided not to proceed with a trial against a number of UVF members named by ‘assisting offender’, Garry Haggarty, who has previously admitted to involvement in five murders of Catholics and others, and in attempted murders and conspiracies to murder. He was preparing to give evidence for the State against former UVF accomplices based in the Mount Vernon area of north Belfast.

The failure to deal with the legacy issues through a properly established truth commission is contributing to the delay in restoring the political institutions. The refusal by the DUP to accept an Irish Language Act and the twin problems of Brexit and the deal by the party to keep the Tory government in power are compounding the difficulties in re-establishing a sustainable power-sharing executive. Meanwhile ‘No Stone Unturned’ has been long-listed for an Oscar film award.

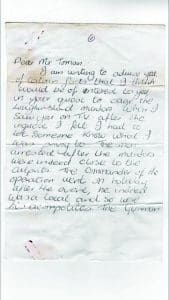

A Man and Village Magazine

The Press Ombudsman has upheld part of a complaint that Village magazine breached the Code of Practice of the Press Council of Ireland. The complaint was made under Principle 1 (Truth and Accuracy) of the Code of Practice. Other parts of the complaint are not upheld.

Village magazine published an article about a recent film documentary on a notorious crime of multiple murders which took place in Northern Ireland some decades earlier. The headline on the article stated that the documentary had named people who had carried out the killings.

The complainant wrote to the editor stating that the headline to the article, and a number of other statements in the article, breached Principle 1 (Truth and Accuracy) of the Code of Practice. He complained that the article presented comment and unconfirmed reports as fact, in breach of Principle 2 (Distinguishing Fact and Comment), and that publication of the name of the village in which he lived breached Principle 5 (Privacy).

The editor stood over the article. He said that the heading merely acknowledged the tragic fact of the murders and was not sensationalist, and that the confounding of fact and opinion alleged by the complainant seemed to be in the documentary rather than in the factual reporting of it. He said he was happy to remove the name of the village from the article, and to correct another reference to the complainant in the article. He also offered to meet in confidence with the complainant and offered to publish a piece by him outlining his concerns and position.

The complainant was not happy with the editor’s response and submitted his complaint to the Office of the Press Ombudsman.

The editor of Village again defended the publication of the article. He stated that he was guided by the credibility and fact-finding expertise of the Northern Ireland Police Ombudsman’s Office reports, and by the reputation of the documentary maker and the “forensic tendency of this particular documentary”. The editor said that he had now removed from the online edition of the magazine the name of the village where the complainant lived and a reference to a business which the article said he operated. He said that at all times he had tried to give the complainant a chance to explain himself in the teeth of grave allegations, and twice informed him that he was willing to publish a piece from him.

As the complaint could not be resolved by conciliation it was forwarded to the Press Ombudsman for a decision. I am upholding this complaint only in relation to the heading of the article. The heading breached Principle 1 of the Code as it stated as fact that the people named in the documentary had carried out the killings, while the documentary referred to people who were suspected of having carried out the killings. This distinction is important as no one has ever been charged or convicted of the killings.

Other parts of the complaint are not upheld. As the article only reported on the contents of the documentary and did not present the contents as fact, the article did not breach Principle 2 of the Code. There is also no breach of Principle 5 of the Code. The complainant objected to the inclusion in the article of the name of his village. Having named the complainant in the article it was not unreasonable to include the name of his village. This would overcome the danger that other people living in Northern Ireland with the same name as the complainant might be thought to have been identified by the documentary maker as having been involved in the killings.

Note: the complainant is not named in the decision as he requested anonymity under data protection legislation. The Magazine appealed against the decision of the Press Ombudsman to the Press Council of Ireland.

Decision of the Press Council

At its meeting on 24 May 2018, The Council determined that the appeal submitted by the magazine was not admissible, as the appeal did not provide sufficient evidence under any of the three grounds for appeal. The Decision of the Press Ombudsman therefore stands.

Frank Connolly