Government projections on how long a lockdown will last hijacked by pessimism not evidence, though readers will make their own minds up as to whether Ireland’s trajectory is more like those of China, Singapore or South Korea than those of Italy and Spain.

By Michael Smith.

It is obligatory to preface articles about Covid-19 with a disclaimer that the author is not an epidemiologist or virologist but this article is about the derivative complex issue of how long the current pandemic may last. In any event virology and epidemiology may not be the professional disciplines best equipped to dictate the appropriate political reactions to the findings of the science of Covid-19. Those reactions should ultimately comprise a balance of the science with an assessment of the social, economic, environmental, cultural and even (because measures should aim to avoid a backlash) political consequences of any decisions. Nobody is expert in all of these and the role in democracies is assigned to politicians in whom there is not generally much popular confidence. Flowing from this, the role of criticising their reactions will inevitably on occasion be filled by journalists not experts.

In Ireland politicians seem to be taking decisions that properly balance all the factors. We have, after all, become a sensible, cautious (who remembers all that change-imperative stuff from February?) body politic where even a discarded Taoiseach pretentiously deploying Churchill can sound reasonable to the point of international encomium. In the UK and the US on the other hand there is a sense that Science is not properly valued, and that the egos of their heads of government who tend to want flash solutions and downplay justifiable pessimism are interposing on the public interest.

So far the high ground here has been appropriated by those who claim we have not acted fast enough. But that is easy to say and most of what the doomers, animated formerly by China and now by horrors in Italy and Spain, recommended has been applied just a few days after they wanted it. Towards the end of whatever period of restrictions we face it is likely that discipline will break down as some people consider the social, economic, environmental and cultural consequences have been disproportionate. Delaying the imposition of draconian measures may have the effect of reducing that breakdown later on and better equipping us to pre-empt a possible second wave. It is of course a balance.

For this reason there has not until now necessarily been a moral deficit for those cautioning against closing society down as fast and as conclusively as possible in the interests of disease prevention. Of course there is a moral deficit for those who flout Science, which is to say those who offer ungrounded opinions on matters they do not understand. Or who understand, and party anyway.

Normally rules would not necessarily import moral imperative but dealing with Covid-19 requires social solidarity and, at least where the advice in favour of rules seems driven by a plausible perception of the common good, it would be a breach of the fragile social contract to flout it. An ancillary challenge is to decipher the advice, and being patient with opaqueness at the edges, as with advice on pubs (until recently), restaurants, public transport, car-sharing, discreet physically-distanced socialising and much more. For those who believe that society evokes obligations it is difficult to argue against following Irish government advice. On the other hand actually going beyond that advice, which purports to be comprehensive, seems unnecessary and – where it threatens proportionality – inadvisable.

So I would not advocate ignoring government advice.

Of course nobody should exaggerate the facts and prognostications. It is unhelpful for example that during the week the Guardian negligently reported “a generation has died” in Bergamo near Milan when in fact 1959 people out of the area’s 1.2m population had died. On 15 March the front-page headline in Ireland’s Business Post was ‘Irish health authorities predict 1.9m will fall ill with coronavirus [sic: in fact the disease is Covid-19]’. Official spokespeople agreed this was accurate. In fact it is not. It is a do-nothing prediction. The word should have been “may” not “will”.

Where I demur is on the crucial area of the nexus of case-projections and how long quasi-lockdowns will probably last. It seems to me that – on this and this alone – policy-makers in Ireland have been hijacked by pessimism not data. It is not that they are not aware of the data and the international research it is that they are deploying it on the basis of worst-case outcomes. Such caution is desirable insofar as it is dictating life-saving policies, but it may lead to inaccurate projections of the medium-term future. As a result they are not duly recognising two things:

- The consequences of the stringent measures we have now put in place and committed to putting in place soon

- The lessons of the epidemiological pattern in China.

The constantly and consistently iterated headline figure of 15,000 projected cases at the end of the month, representing roughly one-third increases daily, which has been more or less registering as predicted since 16 March (though substantially less for the last three days; 906 cases, 4 deaths as of 22 March), turns out to be in the absence of the remedial measures – distancing, closures, that we have actually taken. A similar study by Imperial College London on the UK projected half a million deaths in Britain. The Imperial model’s clear message, though, was not this possible conflagration: it was how small the effects are of half-hearted strategies. Remedial measures, it accepted, would reduce the height of the epidemic’s peak by two-thirds and pushed it from May to June.

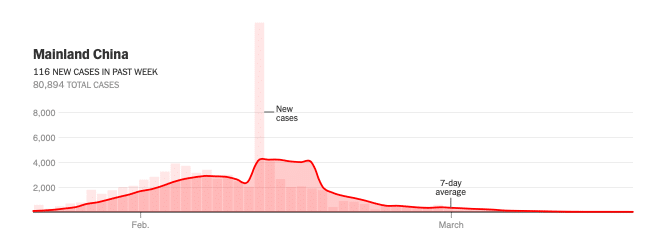

China took remedial measures. So what happened there to the ongoing one-third increases? Just a few weeks after introduction of draconian measures cases dropped. The first case of Covid-19 was detected on 17 November in Wuhan city; the first death was on 9 January; quarantine was imposed in Wuhan and the surrounding Hubei region on 23 January. Figures leapt from around 800 then to 80,000 in mid February but have stayed around that level up to now. By 29 February China was reporting only 427 new cases (its population is 350 times Ireland’s, remember) of which only four were outside Hubei province. By the next day the epicentral city of Wuhan was closing makeshift hospitals as numbers no longer required them.

Within nine weeks of the first death and within seven weeks of quarantine in Wuhan, China had suppressed local cases of the virus. Ireland’s first death was on 11 March and it imposed its restrictions, including pub closings, by 15 March. Nine weeks from 11 March is mid-May; seven weeks from 15 March is the beginning of May. Even a drop from 30% to 20% over the next four weeks would reduce cases by around 90% from 570,000 to 60,000. Is it possible Ireland will be in the position China finds itself in now, in the first half of May?

China, which is further down the line than any other country, seems to be manifesting Farr’s undercelebrated Law of Epidemics which states that epidemics tend to rise and fall in a roughly symmetrical pattern or bell-shaped curve. It is possible we may see its application in Ireland, though it does not allow for a second outbreak or viral mutation.

In China, there has been only one non-imported new infection in the four days since 18 March (https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/18/world/asia/china- coronavirus-zero-infections.html).

Cases remain at around 81,000 and deaths have been confined to 3261 out of a population of 1.6bn – a mortality rate of 0.00000203: the equivalent for a population Ireland’s size of ten deaths. Wuhan city was responsible for very roughly two thirds of China’s cases and deaths (around 49,000 cases and 2,169 deaths), even though it contains only one in every one hundred and twenty five of its population.

According to an article titled ‘Coronavirus: fireworks in Wuhan as checkpoints are taken down, other cities in China ease controls’ in the South China Morning Post of 21 March:

“Since Tuesday, Wuhan people living in residential compounds considered to be ‘epidemic-free’ for at least seven days have been allowed to leave their homes and move around within the compound”.

It also cautioned: “However, not everyone was cheering the development, with some of the city’s 11 million residents questioning how reliable the official data was”. Similarly, the Guardian of 23 March noted that China’s classification, unlike the WHO’s, “does not include asymptomatic infections in its final tally”.

The Sunday Times of 22 March notes that though China is clinging to its projection of 6% annual economic growth and that the vast majority of companies, including 95% of big businesses are back in business, only 40% of them are where they were before the crisis.

In any event the respite admittedly follows enforcement of measures that would be unacceptable in a democracy.

It is not clear how much less would have been achieved if the measures, graphically described by Wuhan author Fang Fang in her Quarantine Diary, had been just what were acceptable in a democracy in an emergency. This of course is key. No travel was allowed into Wuhan City even for humanitarian reasons – with predictable consequences. Car travel was prohibited. Only one person per household was allowed to leave home every three days to buy food. Ubiquitous building security monitored all movements. Two new hospitals were built in Wuhan.

Throughout China the government organised rapid and stringent contact-tracing, testing and self-isolation of suspected cases, and all of their first-degree contacts, using artificial intelligence and computer-based solutions. And even 1000 km away, in Inner Mongolia, mask-wearing was enforced by drones.

However, the measures were unnecessarily repressive. According to the Guardian: “Wuhan-style measures are not a requirement to contain the disease”. Chen Xi, an assistant professor at the Yale School of Public Health, told the newspaper that it “took the lockdown strategy because they covered up for so long that the scale of the crisis was beyond their capacity”.

So, readers will make their own minds up as to whether Ireland’s trajectory is more like those of China, Singapore or South Korea than those of Italy and Spain. My sense is that Ireland has in fact been quite diligent in enforcing reasonable social isolation. It benefits from good Community-rooted social solidarity. It has a young, informed population. It is a very rich country with a better health service than China’s. It will benefit from lessons learnt in, and equipment supplied by, China. It also may benefit from the oncoming change in the seasons, to summer.

Against these advantages must be weighed Ireland’s radically unprepared health service, inadequate contact-tracing and the possibility that government edicts are late or, more likely, under-observed.

Some idea of what good policy may bring in a (flawed) democracy is provided from Singapore which, having suffered SARS was impressively pre-prepared but also, like Wuhan in China, keeps anyone who tests positive in hospital, separated from friends and family. Singapore never went into lockdown though, due to something of a resurgence, it has just started implementing distancing measures. As of 22 March, with a population of 5.6 million it has had only 432 cases and two deaths.

South Korea too provides hope. It has not locked its citizens down or quarantined entire cities, but by free daily tests and clamping down on public events and closing schools has still levelled off new infections without subverting the principles of an open society. It has 8799 cases and 102 deaths and a population of 51.5 million.

For the obsessive, here is Tomas Pueyo’s chart of non-pharmaceutical interventions in the major countries.

So what are policy-makers saying about the trajectory for Ireland? Mostly they are offering prognoses for scenarios where we do nothing to prevent spread of the disease. On 16 March Taoiseach Leo Varadkar said: “We would expect that by the end of the month there would be maybe 15,000 people who would have tested positive for Covid-19…Definitely dealing with this for many months, whether it’s an issue next year or not I can’t say”.

Of course other countries are prognosticating even more pessimistically: A US federal government plan to combat Covid-19 warned policymakers last week that a pandemic “will last 18 months or longer”. The Governmental Robert koch Institute in Germany Teutonically envisages two years.

But this piece is about Ireland and whether the measures it is taking allow a reasonable expectation that we may follow China. This is not being addressed. When asked by Brendan O’Connor on RTE Radio on 15 March to contextualise China for Ireland, one of Ireland’s most vociferous medical opponents of the slow pace of reaction in Ireland dodged the question. The discourse has discounted China.

The difference this makes is in projections for a few months time. I am not going to second-guess our epidemiologists. But I will say that they should be offering projections that address the probable consequences of our fast remedial measures and the significance of the experience in China. What those projections should be I cannot say.

So, in summary (for Ireland at least):

- The government should follow the science

- Government policy and advice seems reasonable

- We should all follow government advice, while understanding that some of it requires clarification

- Government in Ireland seems, in its projections, to have excessively discounted the experience in China and the appropriately draconian measures Ireland has put in place

- It would be useful for politicians in calibrating projections if epidemiologists now underscored these two particular realities

- We should be sceptical about medium-term projections for Ireland including the case being made for cancellation of events planned for the summer

- We should all be humble in the face of a global tragedy and inevitable uncertainty.