2017 marks 25 years since the start of the Bosnian war which followed the breakup of the formerly Communist Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. After Slovenia and Croatia seceded from Yugoslavia in 1991, the multi-ethnic Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina passed a 1992 referendum for independence. Nearly half of its citizens were Bosnian Muslims. Nearly a third were Orthodox Serbs and the rest mostly Croatian Catholics.

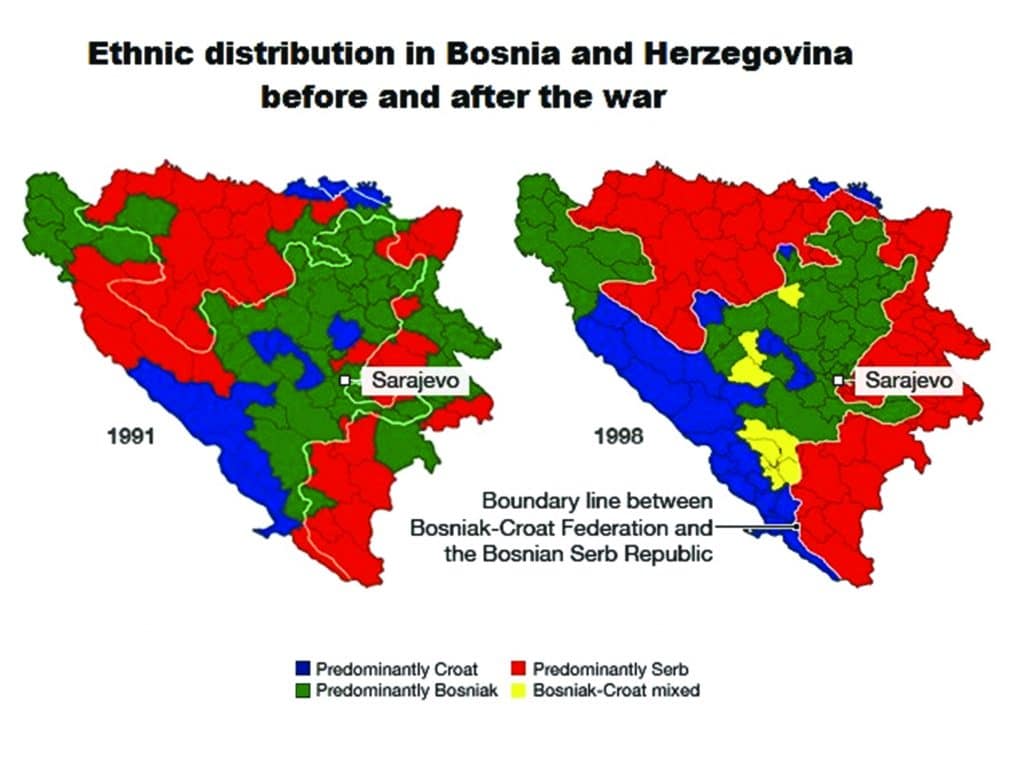

Independence was rejected by the political representatives of the Bosnian Serbs, who had boycotted the referendum though it gained international recognition. The Bosnian Serbs, led by roly-poly poet Radovan Karadžic and supported by the Serbian government of Slobodan Miloševic and the Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA), mobilised their forces inside Bosnia and Herzegovina to secure ethnic Serb territory. War and ethnic cleansing followed. Around 100,000 people were killed, 2.2 million people were displaced, and an estimated 12,000–20,000 women – mostly Bosnian Muslims – were raped. These were Crimes against Humanity. It was the worst conflict in Europe since World War II.

The concept of Crimes against Humanity had its apotheosis in the Nuremberg Tribunal, of which more later, but its inception may derive from the discourse in Sophocles ‘Antigone’ as to whether an immoral law is a law.

In that play, the Rosetta stone of modern natural law, the heroine Antigone observes to the harsh positivist King of Thebes Creon who will not allow her brother, who has fought against him, to be buried properly, allegedly violating the principles of the Natural Law that:

“Yes; for it was not Zeus that had published me that edict; not such are the laws set among men by the justice who neither dwells with the gods below; nor deemed I that thy decrees were of such force, that a mortal could override the unwritten and unfailing statutes of heaven. For their life is not of to-day or yesterday, but from all time, and no man knows when they were first put forth…”.

Therefore Antigone asserts that the positivistic law of Creon is not a law as it is immoral; or perhaps that an immoral law is not a law; or that if a law so violates humanitarian principles it cannot be deemed a law. This, in my view, is the source of Crimes against Humanity.

Later for the Roman orator, statesman and part-time Natural Lawyer, Cicero, positive laws that contravened the natural law could be struck down. Cicero indicated that a legislature which determined that theft or adultery were lawful would be not be making laws, but rather acting as a band of robbers. From Cicero’s perspective, an unjust law is not a law: “Those who formulated wicked and unjust statutes for nations, thereby breaking their promises and agreements, put into effect anything but laws”.

Most famous of all early Christian lawyers, St Augustine of Hippo said “lex iniusta non est lex” (an unjust law is not a law). But still, immorality as such was not deemed a crime against humanity though the ground has been laid.

In jurisprudential terms the last century saw a considerable revival in natural law thinking. The World Wars, the horrors of the Holocaust, the aftermath of colonialism, the nuclear age, economic instability and scientific doubt all cumulatively led to the emergence of human rights from 1945 onwards which I think has morphed into a form of secular religion and all of it related to Crimes against Humanity.

A crucial juristic figure was the German Gustav Radbruch (1878-1949), both a law professor and a government minister during the Weimar Republic. It is often argued that his earlier writings were positivistic – based on the philosophical system that recognises only that which can be scientifically verified or which is capable of logical or mathematical proof, and therefore rejecting metaphysics, natural law and theism. In 1932 he was a relativist in terms of the question as to whether or not moral standards existed in law. He wrote that a judge had an obligation to uphold an unjust law. However, after the Second World War he changed his mind.

In his famous Radbruch’s Formula (Radbruchsche Formel) he argued that where statute law was incompatible with positivist law to an intolerable degree, and where it negated the principle of equality which is central to justice, it could be disregarded. In 1946 he wrote:

“[P]reference is given to the positive law, duly enacted and secured by state power, even where it is unjust and fails to benefit the people unless it conflicts with justice to so intolerable a level that a statute becomes in effect false law and must therefore yield to justice…where there is not even an attempt at justice. Where equality, the core of justice, is deliberately betrayed in positive law then the statute is not merely false law it lacks completely the very nature of law”.

Radbruch suggested that where there is intolerance and betrayal by government, the law ceases to be valid and must yield to justice. For Radbruch justice (Gerechtigkeit) was linked to human rights. Thus in Funf Minuten Rechtsphilosophie he argued for “justice as moral equality – applying the same measure to all or guaranteeing human rights to all”.

As legal philosopher HLA Hart indicates:

“His considered reflections led him to the doctrine that the fundamental principles of humanitarian morality were part of the very concept of Recht or legality and that no positive enactment or statute, however clearly it was expressed and however clearly it conformed with the formal criteria of validity of a legal system, could be valid if it contravened basic principles of morality”.

Radbruch had a broad conception of such fundamental laws. He contended that there was a law which was above statute: “However one may like to describe it: the law of God, the law of nature, the law of reason”. Such a law rendered invalid positive laws that did not conform to justice; he argued that Nazi laws did not “partake of the character of law at all; they were not just wrong law, but were not law of any kind”.

It is important to note that Radbruch’s view was followed in various German cases after the War and was part of the discourse that led to the Nuremberg war crimes tribunal.

Historically much later, in the 1992 cases of Streletz, Kessler and Krenz, former East German Border Guards guards were convicted of offences despite section 27/2 of the East German Border Act that indicated that the protection of the border outweighed the right to life. The German Supreme Court indicated that:

“[A] justification available at the time of the act can be disregarded due to its violation of superior law if it shows an evident and gross violation of basic principles of justice and humanity… The contradiction of the positive law to justice must be of such unbearable proportions that the law must yield to justice as incorrect law”.

The jurist Lon Fuller, in supporting Radbruch, argues that the German courts were correct in striking down the Nazi laws and that a legal system must have certain characteristics if it is to command the fidelity of a right-thinking person. Foremost among those characteristics is the inner morality of the law and, in addition,that the law provides coherence, logic and order.

Fuller, in the context of the ‘Inner Morality of Law’, argues that Nazi law did not have coherence and goodness and instances the use of retroactive legislation, such as the Rohm purge of 1934, which retroactively validated the murder of 70 people. Further, for Fuller, the Nazi laws were deeply immoral for a variety of procedural reasons. In particular; they were not published, they were vague and they could not be interpreted in a congruent fashion.

Fuller argues that, without an inner morality of law, no legal system exists and that the Nazi system lacked the essence of a legal system order and that a citizen only owes fidelity to the law and a corresponding duty to obey the law where the features that make up the inner morality are present.

Thus there is a jurisprudential hinterland to what in the Nuremberg court became Crimes against Humanity – genocide or the mass extermination of a race.

The Nuremberg court and The European Convention on Human Rights were set up with the idea that the cataclysms of the past must never happen again. However, they did. In Bosnia we saw the modern variant: ethnic cleansing. In 1992, the United Nations General Assembly deemed ethnic cleansing to be a form of genocide stating that it was:

“Gravely concerned about the deterioration of the situation in the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina owing to intensified aggressive acts by the Serbian and Montenegrin forces to acquire more territories by force, characterised by a consistent pattern of gross and systematic violations of human rights, a burgeoning refugee population resulting from mass expulsions of defenceless civilians from their homes and the existence in Serbian and Montenegrin controlled areas of concentration camps and detention centres, in pursuit of the abhorrent policy of ‘ethnic cleansing’, which is a form of genocide”.

In 2001, the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) judged that the 1995 Srebrenica massacre was genocide though the Court had no jurisdiction to determine whether it amounted to war crimes and Crimes against Humanity.

By seeking to eliminate a part of the Bosnian Muslims, the Bosnian Serb forces committed genocide. They targeted for extinction the 40,000 Bosnian Muslims living in Srebrenica, a group which was emblematic of the Bosnian Muslims in general. They stripped all the male Muslim prisoners, military and civilian, elderly and young, of their personal belongings and identification, and deliberately and methodically killed them solely on the basis of their identity.

Slobodan Miloševic, the former President of Serbia and of Yugoslavia, was the most senior political figure to stand trial at the ICTY. He was charged with having committed genocide. The indictment accused him of planning, preparing and executing the destruction of the Bosnian Muslim national, ethnical, racial or religious groups, as such, in named territories within Bosnia and Herzegovina.

He died during his trial, on 11 March 2006, and no verdict was returned. Radovan Karadžic a psychiatrist, was the villain on the ground. He co-founded the Serb Democratic Party in Bosnia and Herzegovina and served as the first President of Republika Srpska, the Serbian Republic declared the day Bosnia Herzegovina had declared independence by the Serbs’ assembly in session in Banja Luka, which lasted until 1996. He was a fugitive from 1996 until July 2008 after having been indicted for war crimes by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. On 24 March 2016, he was found guilty of genocide in Srebrenica, war crimes and Crimes against Humanity, 10 of the 11 charges in total, and sentenced to 40 years’ imprisonment. On 22 July 2016 he filed an appeal against his conviction.

I have spent the last week in Bosnia – in Mostar, Sarajevo and Srebrenica. Mostar still seems shell-shocked. 2000 people died there in the war. Many buildings are damaged and have not been reconstructed. A tank did for the sixteenth-century Stari Most bridge, which has been rebuilt. Srebrenica is an eery and declining tourist town, its mines and spa closed since the war.

Sarajevo, the capital, is a place of crossroads, multiculturalism and complexity. It is surrounded by hills from which the Bosnian Serbs encircled the town and viciously shelled it. The defenders could do little about this but there was armed to arm combat and a tunnel which I visited provided supply lines into the town. The tunnel of hope.

Perhaps it is a sign of hope that Bosnia in 2017 most people I spoke to shared the conventional current preoccupations about the onward and unchecked march of capitalism and conservatism; about xenophobia, militancy, environmental catastrophe and inequality.

Twenty-five years on, even after Crimes against Humanity, genocide and war crimes, in freedom and peace there is hope.

David Langwallner is a Professor of Law in the American University, Prague, and a practising barrister.