| • An Bord Pleanála’s manifest ethical weakness in perspective •

The planning appeals board, An Bord Pleanála, has been brought into disrepute by its deputy chairperson’s property deals, by his criminal failed declarations of property interests and mishandled conflicts of interests, and by his receiverships. He must go.

System of Planning Appeals The 1963 Planning Act prescribed that planning appeals from local authorities would be decided by the Minister for Local Government.

An Bord Pleanála formed After years of unease with the corruptible system that resulted, An Bord Pleanála (ABP) was established in 1977 under the Local Government (Planning and Development) Act, 1976 and has ever since been responsible for the determination of appeals and certain other matters under the Planning and Development Acts 2000-2019, and of applications for strategic infrastructure development including major road and railway cases.

It is an independent, statutory, quasi-judicial body.

Change to system of appointment of ABP members Board members were directly appointed by the Minister until 1983 when the system was reformed following unease with appointments of acolytes, including his own constituency advisor, by corrupt Minister Ray Burke in the golden era of Fianna Fáil-led planning corruption.

The reforms established a new ‘arms’ length’ approach where members of the board, who take the decisions, are appointed by a committee chaired by the President of the High Court and selected by different interest groups. When I was chairman of An Taisce I was ex officio on the committee that appointed the chairman in 2002 and I can vouch for the thoroughness of the interview process. Mind you, the system does favour the Minister’s, or at least the Department’s, preferred candidate since the Department’s Secretary General is always a force on the committee, hosts the meetings and reads the rules.

The membership of the board, which is based in Marlborough St in Dublin 1, is determined by the Planning and Development Acts.

A Chairperson of the board holds office for seven years and can be re-appointed for a second or subsequent term of office. The Chairperson is appointed by the Government.

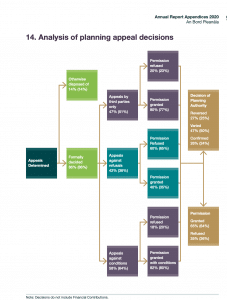

ABP’s performance In 2020, the board received a total of 2,753 cases. Planning appeals (1,956 cases) accounted for over 71% of all cases received in 2020, with two-thirds of all appeals relating to residential developments. Only 47% of all appeals are taken by third parties (i.e. not developers/applicants). The chart below shows that ABP overturns local authorities’ decisions in 27% of cases, varies them in 47% of cases and confirms them in 26% of cases. It grants permission in 65% of cases and refuses it in 35% of cases. Compliance with ABP’s 18-week-decision target continued in an upward trend from 39% in 2018 to 69% in 2019, and 76% in 2020. Legal challenges Between 2017 and 2020, the number of legal challenges brought against decisions of An Bord Pleanála increased by 74%. An Bord Pleanála’s rulings were successfully challenged in 63% of High Court cases in 2020, according to the planning body’s annual report.

There were 51 legal cases in 2020 and the board lost 32. ABP’s legal costs were €8.2m in 2020, more than twice the figure for 2019. The figure was similar in 2021. Legal costs scandalously account for almost half ABP’s public funding and 30 percent of its total budget.

In 19 cases the High Court quashed the planning permission while in 13 cases the board admitted to defects in its decision-making process.

Only 11 decisions were upheld while another eight were discontinued or withdrawn.

The Bord has a terrible track record with controversial SHD (Strategic Housing Development) – large-scale residential applications which bypass local authorities. However, the percentage of overall planning decisions that are subject of legal challenge annually remains very small (only 0.3% in 2020) and only 0.07% of decisions were overturned by the courts.

Financing ABP’s income in 2019 totalled €28 million. Just over €6 million, or 23%, was comprised of fee receipts. Grant funding issued from government amounted to €18.6 million in 2019. Expenditure on salaries and related costs amounted to €16.2 million, representing approximately two thirds of the board’s expenditure in 2019. It had 175.3 whole-time equivalent staff and nine board members.

Expenditure on legal fees amounted to €8.2 million. The balance of expenditure of €5.4 million related to premises and other operating expenses. The surplus for the year was €2.8 million.

Quality of decisions The current board is particularly pro-development. Partly this is driven by edicts, for example on height, density and small apartment sizes, which bind it. The board has always tended to apply local authority development plan standards more stringently than the local authorities themselves. This is because it is not subject to the parochial lobbyings of county councillors.

For a long time that led ABP to higher standards than those of local authorities. However, since the time of former Fine Gael housing minister Eoghan Murphy and his predecessor Labour’s Alan Kelly, in particular, national standards have been lower than those local authorities would like to apply, and the era of a stringent ABP pushing an official government agenda of sustainable development has passed.

Membership of board The Minister for Housing, Planning and Local Government appoints up to nine ordinary board members, including the deputy chairperson, plus the chairperson, making ten members (there is one current vacancy). Normally, board members are proposed by four groups of organisations representing professional, environmental, development, local government, rural and local development and general interests. Sometimes, one member of the board can be a civil servant appointed by the Minister. Ordinary board members normally hold office for five years and can be re-appointed for a second or subsequent term.

Its Chairperson is Dave Walsh who was appointed for the period of seven years in October, 2018. He had been Assistant Secretary in the Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government, with primary responsibility for planning policy, including development and delivery of the National Planning Framework, and housing market and rental policy, with a key focus on coordinated implementation of the Government’s Rebuilding Ireland Action Plan for Housing and Homelessness. A graduate of Trinity College with a BA in the Classics (Ancient Greek and Latin), He also has a Higher Diploma in Education (TCD) and an MSc in Economic Policy (TCD/IPA). As has been the case in the past with board chairs drawn from the Department, Walsh does not have qualifications in planning or architecture. But, like the planning regulator, Niall Cussen another Departmental native, he is infused from top to bottom with the Department’s views on what constitutes tolerable development.

Deputy Chairperson, Paul Hyde Paul Hyde (BSc. Arch, MA, MPlan, MRIAI) was appointed to the Board in May 2014. Simon Coveney, a schoolmate of Hyde at PBC Cork, who in 2007 declared a donation of €2,500 from Hyde’s father Stephen, appointed his friend to the Marine Institute board in June 2012. They yachted together having jointly owned a class 1 Dubois 36 sailing yacht, ‘Dark Angel’ that placed third in the IRC national championship in 2005.

Before ABP, Hyde had been managing partner of the Hyde Partnership, a multi-disciplinary design and planning practice. Sources told Village that he had a lot of experience in the sphere of domestic residences, though according to ABP’s website [the entries are largely written by board members], he also has a wide experience of administration and management as well as industry-specific experience including implementing master plans, complex commercial design projects and managing varied private and semi-public projects within the UK and Irish planning and construction sector.

He has more than 20 years professional experience including as practice manager, architect, planner, development consultant, project manager and advisor. He is a member of the RIAI and IPI professional institutes. He holds a Degree in Architecture (TCD), a Master’s Degree in Planning (UCC), a post-graduate diploma in Marine Spatial Planning (UU) and indeed a Yachtmaster Offshore certificate. Hyde attended Harvard Business School, according to ABP “in the area of effective corporate governance”, and completed a leadership programme at the Institute of Public Administration.

Fine Gael minister Phil Hogan appointed him to ABP in May 2014. In 2019 Eoghan Murphy promoted Hyde to deputy chairman of ABP, increasing his salary from €111,000 to €140,000.

He has special charge of SHDs, a contentious short-term stopgap for facilitating large-scale residential development – bypassing local authorities and the democratic input they import – that are now being wound down because the balance between controversy and efficacy they represent has been poor.

A database compiled by solicitors FP Logue shows that up to last year there had been 250 ‘fast-track’ SHD applications to ABP since 2016, with 71 per cent of them granted – a high proportion of which contravened local authorities’ development plans in some respect: usually height, density, open space or apartment-design quality. Of these 28 had been subject to judicial review by the High Court, with the board losing or conceding an iniquitous 85 per cent of the challenges. It is not a good record for Mr Hyde.

Hyde is one of the most pro-development members of the board. For example in March 2021, ABP rejected Dublin City Council’s proposals to permit only up to 25 storeys for a site embracing North Wall Quay in Docklands where developer Johnny Ronan was planning to build up to 45 storeys. In rejecting the council’s proposed amendments to the local SDZ planning scheme, Paul Hyde’s name was on a decision which said the board considered the Council’s proposed amendments “to be a missed opportunity” to go higher, on what is admittedly a capacious site. The decision’s reasoning said that the fundamental intention of government height guidelines was “not to introduce height for the sake of height, but to introduce and consider heights and densities as a means of accommodating greater residential accommodation within zoned land banks”. The open-ended vision of planning implicit in the statement doesn’t survive much intelligent parsing.

Hyde and the Law and Ethics Hyde also has scandalously broken the law, and ethics legislation.

Mr Hyde doesn’t seem to have appreciated the public interest in stringent planning standards or the need not to have his head turned by a private-development agenda.

The need for stringency and probity from ABP has been particularly dictated by its history outlined above, as well as by the systemic and endemic corruption of the planning process outlined at length by the Planning Tribunal. ABP plays an important role in the Irish body politic and in recent years has done so without ethical taint. However, it now faces allegations of wide-ranging impropriety from Mr Hyde.

According to a recent series of articles in online investigative magazine The Ditch:

• Land registry records attached indicate Mr Hyde is the owner of at least seven undeclared properties.

• Court and other records indicate receivers were appointed to dispose of three of these properties.

• Mr Hyde also has an undeclared 25 percent shareholding in H20, a property holdings company.

• Mr Hyde declared he had no interests in his 2021 and 2022 declarations of interest to ABP (submitted in accordance with section 147 of the Act).

• On 9 March 2022 Mr Hyde voted on an SHD application for a development in Blackpool, Cork. Part of the land of the applicant in that case is located less than 50 metres from the land owned by Mr Hyde’s company (H20 Property Holdings Ltd).

• Mr Hyde signed off on a controversial build-to-rent development on which his brother’s company had worked, carrying out the emergency services access report.

The Law He’s no longer a member of ABP · For a start, according to Section 106 (13) (d) of the Act: “A person shall cease to be an ordinary member [or Deputy Chairperson] of the Board if he or she— (ii) makes a composition or arrangement with creditors” i.e. agrees with creditors that they will take less than the amounts due to them in full satisfaction of their claim.

Mr Hyde has clearly experienced compromising difficulties with several property investments since his appointment to ABP.

• According to The Ditch, in April 2015 Promontoria Aran took over the Ulster Bank mortgage on land in Rathduff, County Cork, owned by Mr Hyde and three co-investors.

• In March 2017 the distressed loan buyer issued High Court proceedings against Hyde and his co-investors but the case was discontinued four months later. According to Cork County Council planning records, the property has since been bought from a receiver.

• Hyde had failed to make repayments on another Ulster Bank mortgage for a property he owned since 2007 in Douglas, County Cork. In October 2017 Promontoria Oyster appointed a receiver to sell the one-bed apartment.

• Hyde had rented the apartment for €950 a month as late as October 2016. In July 2021 it was sold at a distressed property auction for €121,000.

• Receivers were appointed to dispose of apartment 30 Pope’s Hill; 16 Watergold and the land at Rathduff. There are pending transactions on two of the folios.

• Since Mr Hyde on occasion diced with receivership and arrangements with creditors, he should have and must now, leave, indeed legally has already left, the board.

He’s committed crimes • Section 147 of the Act states at (1): “It shall be the duty of a person to whom this section applies to give to [ABP] a declaration in the prescribed form, signed by him or her and containing particulars of every interest of his or hers”. (2) A declaration under this section shall be given at least once a year. (3) (a) This section applies to the following persons: a member of the Board…”.

Section 147(3)(b) of the Act requires a board member to declare “any estate or interest which a person to whom this section applies has in any land…and “any business of dealing in or developing land in which such a person is engaged or employed and any such business carried on by a company or other body of which he or she, or any nominee of his or hers, is a member”.

Failure to comply with the foregoing is an offence under section 147(11) of the Act.

Mr Hyde’s failure to declare at least seven undeclared properties and his 25 percent shareholding in H20 suggest he has committed a crime

• Section 148(1) provides that “Where a member of the Board has a pecuniary or other beneficial interest in, or which is material to, any appeal, contribution, question, determination or dispute which falls to be decided or determined by the Board under any enactment, he or she shall comply with the following requirements: (a) he or she shall disclose to the Board the nature of his or her interest; (b) he or she shall take no part in the discussion or consideration of the matter; (c) he or she shall not vote or otherwise act as a member of the Board in relation to the matter; (d) he or she shall neither influence nor seek to influence a decision of the Board as regards the matter”.

Failure to comply with the foregoing is an offence under section 148(10) of the Act. Mr Hyde acted criminally by flouting (a), (b), (c), and (d) above: by failing to disclose his interest, and voting and otherwise acting as a member of the board also suggest he has committed a crime.

• Mr Hyde failed to disclose to the Board the nature of his interest in the land at Blackpool, Cork, close to an SHD scheme considered by the board and appears to have voted and otherwise acted as a member of the board. This also suggests he committed a crime.

• Unfortunately Section149 (1) of the Act provides that “proceedings for an offence under section 147 or 148 shall not be instituted except by or with the consent of the Director of Public Prosecutions”. ABP should inform the Garda or DPP and so lead the prosecution of Mr Hyde, at least before the DPP takes over.

• Hyde’s brother When asked if was aware that a company directed by the deputy chairperson’s brother had worked on contested developments, ABP told The Ditch it “has no comment”. This of course tends to make ABP itself complicit. While this delinquency is not covered by the Act – which doesn’t cover conflicts of interest over brothers – it does appear to be covered the Code of Practice for the Governance of State Bodies 2016 which applies to its members and indeed by Ethics legislation and guidelines which extend to relations generally.

Complaint to ABP I have submitted a complaint about Mr Hyde to ABP, noting that he has committed criminal offences and is no longer a member of the board and inviting ABP to play a lead role in the prosecution.

Bord Pleanála standards On some level, ABP is aware of the high standards which govern it. According to its latest, 2020, annual report: “Corporate Governance in An Bord Pleanála follows the relevant requirements of the Code of Practice for the Governance of State Bodies 2016. An Bord Pleanála is committed to reviewing its governance policies and procedures on an on-going basis and obtaining up to date refresher training and guidance to assure continued compliance with best practice in this area. An Bord Pleanála has conducted a review of governance arrangements and procedures to ensure appropriate alignment with all relevant provisions of the 2016 Code. An Bord Pleanála is satisfied that it is in full compliance with all relevant/applicable code requirements”. The case of Mr Hyde shows it is not.

ABP says it comes within the scope of the Ethics in Public Office Acts 1995 and 2001 [which covers “any…body, organisation or group appointed by the Government or a Minister of the Government”] and says it has adopted procedures to comply with the Acts. Where required, according to the 2020 annual report, board members and staff have completed statements of interest in compliance with the provisions of the Acts. In the case of Mr Hyde he had not.

|

How ABP has dealt with similar issues in the past

Case 1: ABP member Conall Boland conflict of interest with RPS consultants, Donegal;

ABP ignores

It’s not the only time ABP has run into issues of conflicts of issues but its record is hardly

stringent. Two significant instances related to the Indaver Incinerator in Ringaskiddy.

But the first one I consider dates from 2011. Campaigners against a wastewater plant in

Donegal claimed there was a “conflict of interest” in a decision which granted permission

overruling an inspector’s recommended refusal. It noted An Bord Pleanála member

Conall Boland, formerly technical director of RPS Consultants, was a signatory to the

approval.

The campaigners said in a statement that Mr Boland should have “excused himself” when

the board decision was being taken, as his former employer, RPS, undertook a

hydrodynamic and water quality modelling study for principal consultants as part of the

scheme. ABP ignored the controversy which eventually went away.

Case 2: ABP member Conall Boland conflict of interest with RPS consultants,

Cork; High Court finds objective bias

In March 2021, Judge David Barniville in the High Court ruled that the board’s

decision on Indaver’s Incinerator in Ringaskiddy, Co Cork had been tainted by

objective bias due to the prior involvement of the same member, Conall Boland,

then deputy chairman of the board, in work which he did in 2004 when employed by

RPS MCOS Consulting Engineers. Those consultants were engaged by Indaver to

make submissions on reviews to the relevant local authorities’ waste-management

plans.

The judge was satisfied the work done by Mr Boland had a “clear, rational and

cogent” connection with Indaver’s 2016 application to the board for permission

for the development.

Mr Boland was also the presenting member of the board in respect of the board’s

consideration of the planning application at issue.

The judge noted the local environmental group challenging the decision had made

clear it was not alleging actual bias against either Mr Boland or the board but was

making a case for objective bias, which was denied by the board and Mr Boland.

Having considered the evidence and the law, the judge was satisfied the environmental

group had established a reasonable objective observer would have a reasonable

apprehension the board might not be capable of considering and determining

Indaver’s 2016 planning application in an unbiased and impartial manner.

“The ultimate touchstone is that justice must not only be done but must manifestly

be seen to be done, he said. “It is essential that public confidence in the integrity of

the board’s procedures is maintained”.

A refusal to grant relief on this ground would, in the court’s view, “undermine that

critical public confidence”.

Before the Barniville decision in 2018, ABP had taken a notably open position on

potential conflicts affecting board members and Indaver.

Case 3: Two board members excluded but John Connolly’s multiple former

connections to Indaver somehow not deemed prejudicial by ABP chairperson, though he

excluded himself at the last minute

According to a report by Eoin English in the Irish Examiner (2 June, 2018), a memo

written by the then Chairwoman of An Bord Pleanala, Dr Mary Kelly, showed she was

satisfied that no members of the board who were involved had a conflict of interest in relation

to Indaver’s proposed incinerator at Ringaskiddy. In fact, she had gone so far as to exclude two

board members to ensure that there could be no perception of a conflict of interest or of any

form of bias.

Board member John Connolly, who remains a member in 2022, was not among those excluded

by Dr Kelly, the apparent implication being that she did not believe him to have either a genuine

or perceived conflict of interest in relation to the case.

For the 14 years before his appointment to the board in September 2017, Mr Connolly had been

a director of the Irish Waste Management Association (IWMA), a trade association and lobbying

group that included the applicant, Indaver.

Connolly, who was appointed to ABP on the nomination of IBEC, had also been the Chairman of

the Waste and Resource Management Working Group of an IBEC Committee that had written to

An Bord Pleanála in March 2016, just weeks prior to the oral hearing, lobbying in favour of the

Ringaskiddy incinerator.

Furthermore, the IBEC Committee in question, the Environmental Policy Committee, is chaired

by none other than Indaver’s Executive Chairman, John Ahern. Connolly remained on the

Committee with Ahern until his appointment to ABP.

Under An Bord Pleanála’s code of conduct Connolly was bound to disclose relationships that are

of relevance to the work of the Board but Dr Kelly stated that no acting board members had a

conflict of interest.

Connelly recused himself from the case on 3 May 2018, the day the Board met to decide whether to

grant planning permission and over two years after the oral hearing had taken place.

ABP was aware of Connelly’s work with the Irish Waste Management Association and his role

within the Environmental Policy Committee as details of both are included on the Board’s website.

It is unclear to what extent Connolly had access to the case files but from the available records it is

apparent that he, along with the other board members, was briefed on the case.

Vulnerability for ABP

The cases suggest an ethical vulnerability in ABP.

The case of Mr Paul Hyde suggests that vulnerability is enormous and needs to be staunched to avoid

fundamental reputational damage to ABP, an important agency of state in a sphere that, in Ireland,

particularly, resonates ethically.

Resignation

Mr Dave Walsh, chairperson of ABP, must act as an agent of the law and probity, insist on the resignation

(or more accurately recognition of terminated membership) of Mr Hyde and adopt a central role in his

prosecution.

If the issue is not dealt with properly Village will organise protests highlighting ABP’s regressive approach

to planning and the environment, its poor record on housing, affordable housing, balanced regional

development and – especially – this ethical taint.