By Ronán Lynch.

The vast sums accruing to the 1% present at least one problem for the most avaricious: how to hide their money. With vast amounts of wealth invested in property it may be the case that offshore accounts, tax evasion and property bubbles are not unconnected. The return to life of the Ansbacher investigation into offshore accounts held by senior Irish politicians and businesspeople from the 1970s to the mid-1990s reminds us how things used to be done. Some might argue that little has changed.

Under the new protected disclosure legislation, serving civil servant Gerry Ryan, who began investigating the Ansbacher accounts in 1997, has contacted the Public Accounts Committee to voice concerns that tax evasion among high-ranking politicians with offshore accounts was not properly investigated. Mary Lou McDonald said they were “household names” from Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael and the Progressive Democrats. Responding to the disclosure, the government said that the files had already been forwarded to the “relevant authorities” which apparently did not include the Gardaí, as Minister Richard Bruton finally forwarded the files to Gardaí on Monday 10 November. Ansbacher was closely associated with CRH, the giant Irish business which has connections across almost all political parties. In ‘A History of Scandal’, (Village Oct/Nov 2012), Michael Smith outlined a series of serious instances of failure of the “relevant authorities” to lay a finger on CRH; it materialised, for instance, that Justice Moriarty had £500,000 worth of shares in CRH that in his opinion precluded him from investigating the company. Now it emerges eminent progressive turned President of the High Court, Declan Costello, who investigated the bank’s Cayman operation as a High Court inspector in 2000 had a domestic Ansbacher (ie Guinness and Mahon) account though he had ‘forgotten’ it when denying it to Ryan. He resigned as inspector citing ill health, He died in 2011.

Ansbacher bank became a household name in Ireland from stories emerging from the McCracken Tribunal in 1997 as it uncovered a complex series of payments from Ben Dunne to Charles Haughey that eventually landed in Ansbacher bank, formerly the Cayman Islands branch of Guinness & Mahon Bank. The accounts were run by Haughey’s bagman Des Traynor and John Furze, an English-born banker who ran the Cayman Islands end of the venture. Furze’s career was straight out of a John le Carré novel. He was instrumental in establishing the offshore banking system in the Cayman Islands, arriving there in 1967 at the age of 25. When his name was first mentioned in the Irish Times in 1996, the paper wrote that it considered Furze to be a fictitious name. Another early Irish Times report on the island referred to John Grisham’s novel ‘The Firm’ for context. Yet by 1996, Des Traynor was already dead, and Furze had travelled to Ireland for the funeral and to remove paperwork from Traynor’s office at CRH. Furze died in July 1997 following heart surgery and by that stage he had destroyed much of the paperwork.

A full 200 customers of the bank were identified in a 2002 report but no prosecutions resulted. Revenue later cited a number of reasons for not bringing prosecutions, including the lack of original documentation, an inability to compel Cayman Island entities to release documents, and the elapse of more than 10 years in bringing cases. Despite the criminal-law inertia, by the end of 2012 the Revenue Commissioners had recovered more than €112 million in unpaid taxes and penalties, (an Irish solution to a Cayman Islands problem) but now it appears other names have been identified and efforts by Gerry Ryan to recover documents that may have aided a prosecution were stymied.

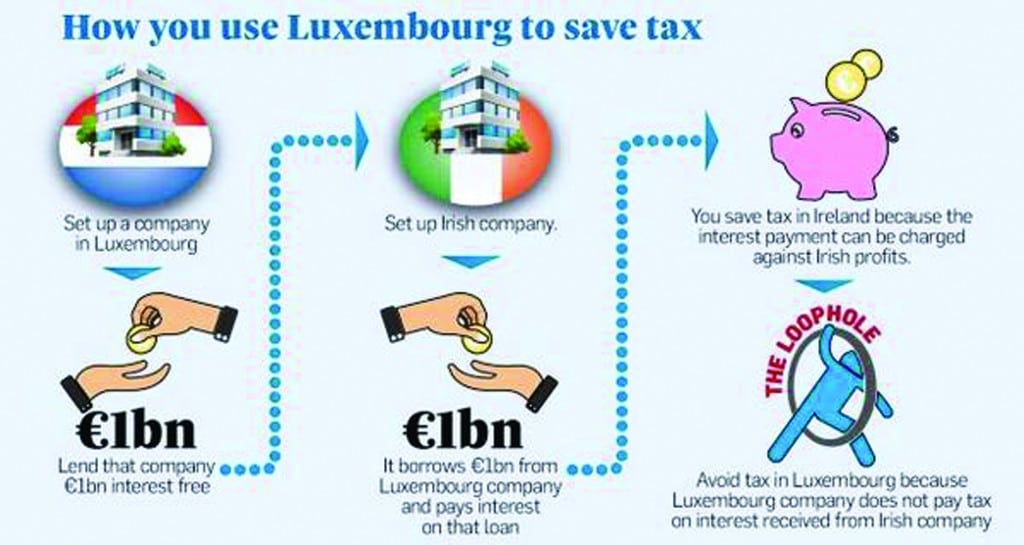

The return of Ansbacher reminds us of the scale of tax evasion and tax avoidance on a personal and corporate scale. The recent ‘Lux:eaks’ story involves PriceWaterhouseCooper, several of the world’s biggest corporations, and the now European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker, who was Prime Minister in Luxembourg for much of the relevant period from 2008 to 2010, and after a short period in apparent hiding he has now emerged to “take responsibility” for the “unethical” policy, and possibly spear Ireland’s Corporation Tax policy. Interestingly, when the story broke, the Cayman Compass news website promptly issued an editorial in support of Juncker.

The Cayman Islands, wealthiest of the Caribbean islands, ranks as the fourth largest tax haven in the world, with dourer Luxembourg seizing second place, according to the Tax Justice Network. The islands feature high in the 2013 ICIJ project Offshore Leaks which contains details of over 100,000 secret trusts and funds based in the Cook Islands, Singapore, the Cayman Islands and British Virgin Islands. The ICIJ developed the information into a searchable database, which is open for public use on its website www.icij.org. Ireland delivers 54 officers and master clients. John Ignatius Quinn, more infamous as Séan Quinn bankrupt former richest man in Ireland is among them along with 1614 offshore entities and 51 listed addresses. Interested readers are recommended to dive into the database, as the search programme visually displays the linked entities. As the ICIJ website points out, however, there are legitimate uses for offshore companies and trusts.

Among the main findings by the ICIJ about offshore accounts are that government officials and their families and associates have embraced the use of covert companies and bank accounts; the mega-rich use complex offshore structures to own property and other assets, and the world’s top banks are not adverse to providing their customers with secrecy-cloaked companies in offshore hideaways.

In the analysis of these unregulated capital flows, the ICIJ was moved to ask this question: where does the money end up being spent or invested? A story titled ‘Hidden in plain sight: New York just another island haven’ traces the flow of international money into New York’s highly priced apartments and condominiums. The story notes that New York property had traditionally been a place for Mafia families to invest their illicit profits, although they stuck to small, low-key properties which they rented out as bars or clubs. It noted that New York along withMiami, Dubai and London are the major world cities experiencing an influx of capital into real estate, with the owners often remaining hidden behind shell businesses. “Because many buyers go to great lengths to hide their interests in New York properties, it’s impossible to put a number on what proportion of buyers from overseas are laundering ill-gotten gains”, it says. “Many act in an above-board manner and use tax loopholes that are legal in their home countries. But it’s clear that New York’s public officials and its real estate industry embrace the wealthy and powerful without much thought to where their money comes from”. Over recent years, Irish residential and commercial property markets seem to have surrendered to the mercy of peripatetic international real estate investment trusts and individuals with deep pockets. Perhaps Dublin should be added to the list.

Ireland featured in another ‘leaks’ operation. In 2009, Wikileaks released a batch of diplomatic communications, now beautifully indexed at https://cablegatesearch.wikileaks.org/search.php, including what became known as the ‘Ireland Cables’, which showed that the US government had willing ‘confidential sources’ at the highest level of government, the civil service and the diplomatic service. They also showed that the US government wasn’t impressed with Irish governance. US ambassador Dan Rooney wrote to Washington that Irish elected officials were “an often unaccountable political class” that awarded themselves undue perks. Unless the government acted quickly, “Ireland’s tarnished reputation could blacken further”, he noted. •