As the French courts prepare to prosecute Ian Bailey in absentia, there is growing speculation that gardaí targeted him for the murder of Sophie Toscan du Plantier in order to protect the real suspect.

The skies were still dark over the West Cork countryside when Martin O’Sullivan set off from his home in Goleen on a crisp morning two days before Christmas. It was just after 7.30am as he made his way to work along the quiet road to Durrus passing a winding boreen that leads to the white-washed home of Sophie Toscan du Plantier.

As he drove north towards Bantry, leaving the French filmmaker’s secluded farmhouse behind, a blue Ford shot up behind him at high speed. O’Sullivan was forced to slam on the brakes as the car overtook him on a dangerous bend and nearly ran him off the road. He noticed its headlights were on and the rear number plate was red. He believed it was a Fiesta.

Several hours later, shock and sadness replaced the festive mood throughout Ireland as news filtered through that the 39-year-old mother of one had been found murdered on the laneway leading to her holiday home overlooking the Atlantic in Toormore, Schull. It was December 23, 1996.

Du Plantier was found in a blood-soaked T-shirt, white leggings and a pair of laced-up boots. She had been bludgeoned to death with a rock and a concrete block. She put up a considerable fight but sustained more than 50 injuries to her head, face and body in the attack and was left almost unrecognisable. She had lacerations on her hands and arms. The then State pathologist John Harbison also believed she had been kicked or held down by the neck and wrist with a ‘Doc Marten’ boot, whose prints were also found on the laneway near her remains.

In the days that followed, Martin O’Sullivan gave a statement to gardaí about the suspicious car he had seen, telling them he was fairly certain it was not from the immediate locality. It was a critical sighting that occurred close to the time and location of the murder and could hold the key to unlocking the case. O’Sullivan expected gardaí to carry out an appeal asking for the public’s help in identifying the driver but they never did; nor did they perform door-to-door inquiries in the locality where the suspicious car had been seen. Why was this? Did they have a motive in protecting the identity of the driver?

It is just one of the countless unsettling incongruences in an investigation which many people in Cork and across Ireland now believe was mangled not by accident but by design. There is a growing sense that the persecution of English journalist Ian Bailey (61) by the gardaí, which has endured for 22 years and continues to this day, may have been motivated by something more sinister than the need to find a suspect to satisfy her family and the authorities in France. Speculation is rife that gardaí targeted Bailey because they already knew who the real killer was and were protecting him.

Allegations have emerged that a senior member of the force may have been responsible for Sophie Toscan du Plantier’s death. The officer at the centre of these claims, who is now deceased, was a notoriously violent person and a sexual predator infamous for having affairs with women, particularly foreigners. A married man who was strikingly handsome, he was a rampant alcoholic who is described as having abused his power whenever he could. One local portrayed him as being “crooked as a ram’s horn”.

He was known for rustling cattle and sheep from farmers who had committed minor offences and he was in a position to blackmail. He also drove a blue Ford car.

It is believed the officer may have come into contact with du Plantier because of her fears about drug-dealing in the countryside close to her. Some in the area claim he had a sexual encounter with the French woman, whose love-life was complicated and fraught, but that he was subsequently rejected by her.

The violent nature of the killing has always been indicative of a ‘crime of passion’ carried out by a scorned lover. The garda at the centre of these allegations was not involved in the investigation. On his deathbed, he was said to be a profoundly disturbed man. The shocking allegations against him however remain unproven.

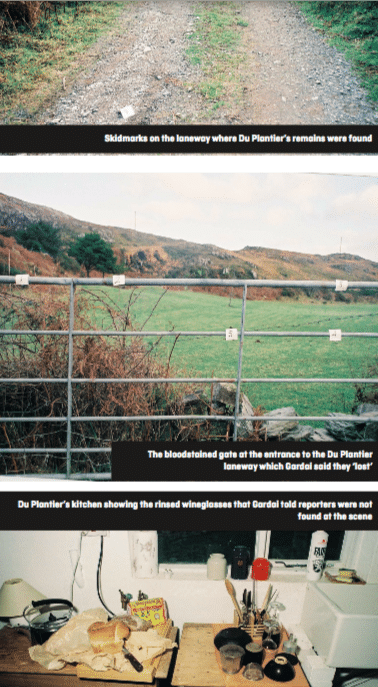

From the very start of their investigation, gardaí were keen to control the narrative of what might have happened to the French woman. For some reason, they dismissed suggestions that she had a guest in her home in the hours before the murder, rejecting rumours that two rinsed wine glasses had been found beside her kitchen sink. In his book about the case called ‘Death in December’, Michael Sheridan said the wine glass story was a myth. He was assisted in his research by the gardaí. But images from the crime scene disproved this claim and two wine glasses were indeed found draining in the kitchen. More suspicious still was the fact that no fingerprints were found on the glasses – at least according to gardaí.

Apart from their relentless targeting of Bailey, the destruction of vital evidence from the crime scene supports the theory that the investigation was deliberately botc

The gardaí have also never accounted for the ‘loss’ of witness statements and suspect files as well as of a document outlining why Bailey and his partner Jules Thomas were to be classified as suspects. A bottle of wine found at the crime scene is also believed to have disappeared as well as a small red hatchet kept inside the doorway of du Plantier’s home which her housekeeper Josie Hellen noticed was missing.

Fresh skid marks on the laneway where she was found suggest a visitor had arrived and left in a hurry but they do not appear to have been identified. Did they belong to the Ford seen speeding nearby shortly before her remains were found?

The brutality of the murder is reflected in images of the victim’s body which are horrifying. They also suggest the attack may have been prolonged and that she was chased to her death.

When training to become police officers, young recruits, including gardaí, are taught a fundamental principle of forensic science – a phrase formulated, ironically, by a man known as the ‘Sherlock Holmes of France’ Dr Edmond Locard. It is that every contact leaves a trace.

Given the number of injuries inflicted on du Plantier and the frenzied nature of the attack, it is inconceivable that the killer did not leave a single trace of hair, skin, blood, saliva or clothing at the scene yet gardaí claimed no such materials were ever found. The victim had a clump of hair in her tightly clenched hand, which they said was hers, another dubious assertion.

The timeline of events presented by officers is also questionable. They said that du Plantier’s remains were found by her neighbours Shirley Foster and Alfie Lyons (with whom she had a testy relationship) at the bottom of their shared lane at 10.10am. Gardaí arrived shortly afterwards at 10.38am. Scandalously, it was another 24 hours before pathologist John Harbison arrived to carry out the post mortem. Because the body was exposed to the elements for an entire day and night, a time of death could not be determined. However, Harbison’s autopsy noted that the remains of a recently ingested meal of fruit and nuts were found in du Plantier’s stomach. This is more indicative of breakfast than of an evening meal. An uncovered loaf of bread in the process of being sliced was also found in the kitchen.

While it appeared the victim had company the night before, there was nothing to suggest her guest stayed overnight. She had spoken to her husband Daniel before she went to sleep and had agreed to return to France for Christmas following some discussions on the matter.

Questions linger as to why du Plantier chose to come to Ireland on her own just five days before Christmas and was undecided as to whether she would return. Her marriage was an unhappy one but the idea that her husband ordered a hitman to kill her is unlikely as he seems to have been more focused on his next acquisition rather than worrying about his wife’s extramarital affairs. It was he who bought the isolated farmhouse for her in 1993 but rarely came with her when she visited.

Du Plantier was worried about drug-dealing going on in the nearby countryside and could have made some dangerous enemies as a result, individuals who may have been in the pockets of certain gardaí who had ‘dirt’ on them.

Her remains were found at the bottom of the steep laneway running down from her property, her nightwear caught in brambles and a navy dressing gown by her side. This had either been torn off during the struggle or discarded by her to ease her escape. The door of her home was on the latch with the keys on the inside. Her boots were laced up indicating she willingly went outdoors. There was no sign of a disturbance in her home, apart from a splash of blood found on the outside of her front door and believed to be hers. Having been rejected the night before, did her mystery guest return the following morning in a drunken rage, lure her outdoors and chase her to her death?

For more than two decades, An Garda Síochána have proactively targeted Ian Bailey, spending millions in public money in the process but failing to produce a single shred of evidence against him. He was first arrested on suspicion of murder on his birthday in February 1997, and again in January 1998. Two years later, the DPP (Director of Public Prosecutions) issued a direction that Bailey should not be prosecuted due to the lack of available evidence.

Bailey, who was a reporter for the Sunday Tribune and the Daily Star at the time, was the first journalist on the scene on the day of the murder in December 1996. Being British and unlike the rest of the Irish media pack, he was somebody the gardaí were unable to control and, from the beginning, his stories took an independent look at the case.

In his work, he asked awkward questions about du Plantier’s complex love life and enquired why officers seemed to be making no progress in the case. This embarrassed and irked gardaí, who were used to being able to manage the media and the message. It also explains their animosity towards him and why they may have wanted to shut him down.

From then on, they engaged in a frenzied scheme to paint him as the chief suspect, spreading the word around West Cork that they had their man and falsely claiming his DNA had been found at the scene. After his first arrest in February 1997, Bailey claims he was told by a garda that even if they didn’t manage to pin it on him, he would be found dead sooner or later with a bullet in the back of his head.

One of the more deplorable tactics deployed to implicate him in the murder was the gardaí’s use of local drug-dealers to make false statements against him.

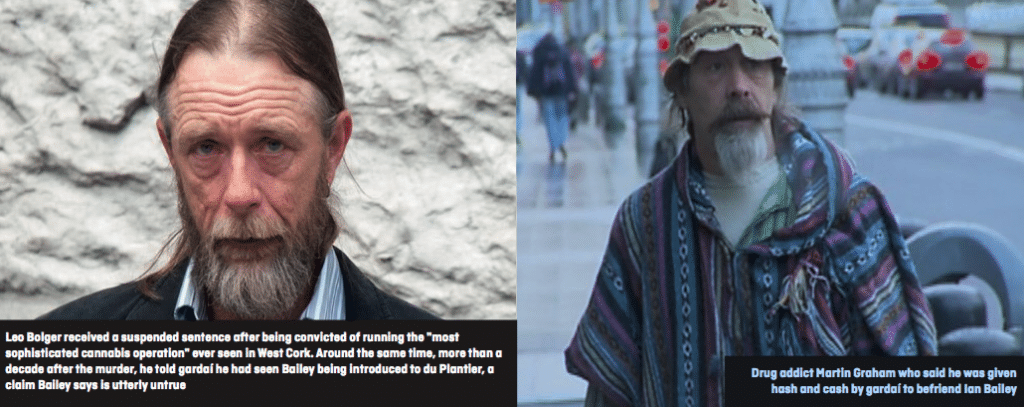

In 2010, Leo Bolger came before Judge Patrick J Moran in Cork Circuit Court charged with running a massive drug production plant near du Plantier’s home. During the hearing, a garda described his cannabis operation as the “most sophisticated” ever witnessed in West Cork. Bolger (45) had built a large bunker in an overgrown part of his land where he cultivated cannabis plants using advanced hydroponics, heating, watering and lighting systems that revolved around the plants to enhance cultivation. At the time, the street value of the plants was at least €150,000.

Bolger pleaded guilty to the offence, which carried a mandatory minimum sentence of 10 years and up to life imprisonment. However, the prosecuting garda informed the judge that the defendant had been assisting them with another case. To the consternation of the court and the defence team, Bolger was given a suspended sentence as the sympathetic judge stated he was “perhaps trying to survive in the magnificent peninsula of Dunmanus Bay”.

Bolger had in fact been ‘assisting’ gardaí in their case against Bailey. Bolger, who had done odd jobs for du Plantier from time to time, claimed he was present at the property one day in 1993 when he saw her nearest neighbour Alfie Lyons introducing her to Bailey. Remarkably, Bolger only revealed this some 14 years after the murder.

Alfie Lyons, also alleged to be a cannabis user, made a similar claim to gardaí about Bailey in the weeks after the murder. Bailey accepts he was present in Lyons’ garden about 18 months before the murder and that du Plantier was pointed out to him in the distance by Lyons, but he has consistently denied ever meeting or being introduced to her.

The most explosive document produced about the du Plantier case in the last two decades is a report written by the office of the DPP in November 2001. It was scathing in its assessment of the Garda investigation and expressed grave reservations about the veracity of statements taken from certain witnesses. It was withheld from Bailey for almost a decade.

Among the litany of highly suspect witnesses referred to was Marie Farrell, a Longford-born mother of five who said she was coerced by gardaí into making a statement wrongly identifying Bailey as the man she claimed to have seen at Kealfadda Bridge in the early hours of the morning of the killing. The DPP pointed out that this bridge, which is on a main road about two kilometres from the du Plantier home, was not on the way to or from it in the context of Bailey’s property.

Farrell said she had been in a car that night with a man who was not her husband. In 2005, she retracted her statement, saying gardaí had blackmailed her into making a statement against Bailey in return for not telling her husband about the man she was with. She said they had doggedly pursued her to make false allegations against Bailey and provided her with a Garda mobile phone for discussing the case. It is also alleged that in 2006, a senior officer queried as to whether Garda funds could be used to pay for fines, including speeding fines, owed by Farrell.

Martin Graham, a destitute ex British soldier, convicted criminal and drug user living in West Cork, was also recruited by gardaí to implicate Bailey by befriending him and trying to ‘soften’ him up. In return, Graham said he was given significant quantities of cannabis in a Garda evidence bag, poitín and cash. Officers also offered to buy him clothes and said du Plantier’s family would be very grateful for a favourable statement that would link Bailey to the murder.

Senior gardaí put relentless pressure on Graham. He claimed on one occasion Detective Jim Fitzgerald, who also ‘managed’ Marie Farrell, took him to the pu

Pressure was also put on the State Solicitor for West Cork, Malachy Boohig. He was requested by senior gardaí to ask the then Fianna Fáil Justice Minister John O’Donoghue, a former classmate at UCC, to get the DPP to prosecute Bailey because there was “more than sufficient evidence to do so”.

Boohig declined, saying such a step would be entirely inappropriate. He subsequently told the then DPP Eamonn Barnes of the “improper approach” made to him by senior officers.

The DPP’s comprehensive report vindicated Ian Bailey and concluded the gardaí had no credible evidence to implicate him in the crime, and that a prosecution was not warranted. It noted that when the gardaí had first started to target Bailey in the days after the murder, he had willingly offered his fingerprints and blood for analysis even though he was under no legal obligation to do so at that point. The DPP also stated that being a crime reporter and aware of the nature of forensic evidence, Bailey would have known that the assailant must have left traces of blood, skin, clothing fibres or hair at the scene so to offer his own DNA at that point tended to indicate his innocence.

The DPP’s report found that the arrest and detention of Bailey’s long-term partner Jules Thomas for the murder was unlawful and that she was arrested in order to obtain information which could be used against Bailey. During her interviews, she was wrongly told by gardaí that Bailey had confessed to the murder.

In their panic to have Bailey prosecuted, gardaí spread fear about him throughout the locality and urged the DPP that it was of the “utmost importance” that he be charged immediately as “there is every possibility he will kill again”. They also said witnesses living close to him were in imminent danger and that the only way to prevent a further attack or killing was to take Bailey into custody.

Local people were made to feel that if they showed any support for him they would incur the disapproval of the Garda. The force also used the media to spread lies about their ‘suspect’ and many reporters willingly obliged without asking any questions. Hundreds of communications between journalists and gardaí were unearthed during Bailey’s civil action against the State. The press and photographers were tipped off about his arrival at Bandon Garda station after his first arrest. The PR campaign against Bailey was a success as many Irish people formed an impression in their mind that he must have been responsible.

Du Plantier’s family have also been subjected to a stream of propaganda about Ian Bailey to the point that they too became convinced he was the killer. The officer in charge of liaising with France in the early stages was disgraced former commissioner Martin Callinan, whose career would eventually be brought to an end by the case, in 2014.

The bizarre circumstances leading up to his resignation were fuelled by the discovery in 2013 of tapes of phone conversations unlawfully recorded at Bandon Garda Station, where the du Plantier investigation was headquartered. These included 36 conversations between gardaí and Marie Farrell, and about 18 recordings of conversations with Martin Graham. They only came to light as a result of a discovery order by Ian Bailey’s legal team.

In March 2014, on the day the Government revealed the existence of the secret recordings, Callinan resigned with immediate effect. It subsequently emerged that he had sought permission to destroy the tapes but the then Attorney General Máire Whelan ordered him not to. On the day before Callinan’s resignation, she informed the Taoiseach Enda Kenny of her belief that gardaí had been involved in widespread illegal activity.

This led to the establishment of the Fennelly Commission. It concluded that gardaí were prepared to “contemplate altering, modifying or suppressing evidence” that undermined their claim that Bailey was responsible.

Máire Whelan originally told the Commission that the phone-tapping scandal involved “a complete violation of the law” by gardaí and was a “total disregard” for the rights of citizens. But a spectacular U-turn followed when she changed her story and said she had exaggerated the facts and regretted her trenchant language.

In the eyes of a scandal-weary public, what looked like payback time materialised last year when Whelan was appointed as a judge to the Court of Appeal. The development caused uproar in the Dáil. Proper procedures had been ignored and it emerged that she had not even applied for the position.

The Government was accused of rank cronyism by the opposition. Fianna Fáil said the law had been “circumvented” and that there would be consequences for their ‘confidence and supply’ agreement with Fine Gael. Their claim of outrage is just one of many that came to nothing more than that.

Whelan’s promotion coincided with Leo Varadkar’s first week in office as Taoiseach. The cabinet must have known that the controversial appointment risked the stability of the Government yet they went ahead with it. Was this because Whelan had done them a favour by toning down her original claims about Garda criminality? Could it have been because she became aware of the unlawful measures gardaí had taken to implicate Bailey in a crime he did not commit?

Whelan is not the only member of the legal profession to have benefited from the Garda campaign to frame Bailey. Five judges who ruled in favour of the State against him were also swiftly promoted.

The Garda Ombudsman (GSOC) has spent an inexplicable six years investigating Bailey’s complaint of corruption and misconduct to it. GSOC head Judge Mary Ellen Ring has yet to publish her report – one of numerous reprehensible delays involving her office.

The authorities in France are forging ahead with their prosecution of Bailey, despite a ruling by the Irish Supreme Court that he should not be extradited. Before the end of the year, a Parisian court will try him in absentia relying on fake Garda ‘evidence’ which was demolished by the DPP here years ago. In a case which makes a farce of both the Irish and French justice systems, the decision of the court is likely to go against Bailey.

It will be yet another sorry chapter in this sordid tale of corruption and cover-up which has denied Sophie du Plantier and her family justice while destroying the life of an innocent man and his partner. But it is unlikely to be the final one.

It is now dawning on the people of West Cork that they have been duped by the gardaí and the mainstream media about the case for more than two decades.

They are starting to ask why the force were so desperate to set up a man who clearly had nothing to do with the crime. Why did the gardaí instil terror throughout Cork about him?

Why did they threaten so many gullible witnesses to make statements against him? Why did they claim not to find DNA belonging to the real suspect when he must have left a trace? Why did they ‘lose’ so much evidence, including a large iron gate? Many people are reaching the same conclusion: that it must have been done to shield the real killer who was clearly somebody they needed to protect.