Currently there is no affordable housing scheme, no intention to introduce one, no definition of what an affordable house is, and legislation underpinning the previous scheme (removed in 2011) has been rescinded.

Increasing house prices work well for many: they improve the profitability and feasibility of many projects; land values increase; bank balance sheets look healthier; the positions of those in negative equity and investors improve. However, in the absence of counter-balancing measures, affordability for households on modest incomes are negatively affected.

What is affordable housing?

Affordable housing schemes are typically aimed at helping lower-income households buy their own homes. They offer eligible first-time purchasers the chance to buy newly constructed dwellings at significantly less than market prices. We had such a scheme in Ireland. Under the Planning and Development Acts 2000- 2002, families were eligible to buy an affordable house provided under the Affordable Housing Initiative if 35% of their income was not sufficient to enable them to buy a house. The scheme was discontinued in 2011, with government housing policy now relying on the private sector for the delivery of affordable housing for sale or rent.

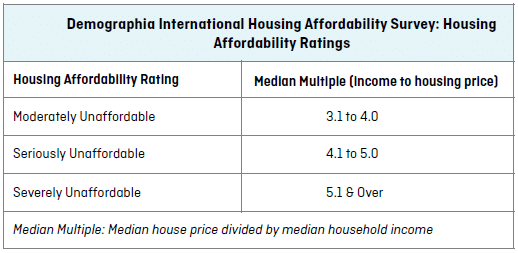

The ‘Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey’, now in its 13th year, covers 406 metropolitan housing markets in nine countries – Australia, Canada, China, Ireland, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, the UK and the US. Over 90 major metropolitan housing markets with populations of more than 1,000,000 are included. Affordability is defined as follows:

The Survey reported that: “Housing affordability continued to decline in Ireland’s only major metropolitan area market, Dublin, where the Median Multiple reached a seriously unaffordable 4.7 in 2016, up from 3.3 in 2011. Dublin could be headed toward the severe unaffordability reached during the housing bust in 2008”. So how did we end up in this position?

Government Housing Initiatives

High house prices have led to calls for the easing of supply-side restrictions such as opening up more land for development and speeding up the planning-approval process. Government policies have reduced costs to developers, thereby improving the feasibility of their proposals. They will also provide funding for localised infrastructure to further facilitate development in the private-new-homes sector (known as LIHAF).

There have been three main government initiatives aimed at improving affordability. So, how have these policies performed?

Development Contribution Rebate Scheme 2015

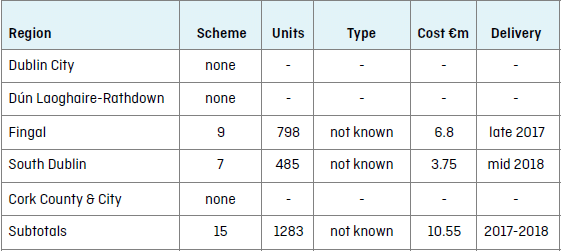

The Planning Rebate Scheme was introduced in November 2015 and aimed at enhancing the viability of construction of affordable housing in the areas of greatest need – Dublin and Cork. Developers could apply for a part refund of development levies (a fee paid per square metre of developed housing) in schemes where a minimum of 50 units would be sold for €300k or less per unit in Dublin (€250k in Cork) by December 2017. Uptake has been very low. It is unclear if any of these will be family units – the type of housing to be developed is not specified in applications and therefore some may be one-bed units or studios not suitable for families.

The numbers of expressions of interest that have been received for the scheme from 2014- 2017 to date are as follows:

Infrastructure Funding- LIHAF 2016

In September 2016 a Local Infrastructure Housing Activation Fund (LIHAF) was announced by former Minister Simon Coveney with the intention of addressing affordability and a perceived infrastructure deficit that was holding up completion of housing sites. It was expected that by 2022 almost 23,000 units would have been completed as a result of the deployment of LIHAF. A requirement of the receipt of LIHAF monies was that 40% of the housing developed was to be ‘affordable houses‘, offered for sale at ten-or-more percent below the market average (less than €300,000 in Dublin). By March 2017 LIHAF funding of up to €226m for infrastructure had been confirmed for 34 sites, without any legal agreement with developers and land-owners to provide affordable housing. The affordability criteria appear to have been abandoned though funding was allocated to sites in Dun Laoghaire-Rathdown and Dublin City. It is notable that there had been no expressions of interest from developers for the planning rebate scheme months earlier, meaning that officials already knew there was no chance of getting affordable houses below €300,000.

‘Repair and Leasing scheme’ 2016

This €32m fund was established in February 2017. In this scheme, a local authority or approved housing body would fund repairs to suitable houses in return for a lease of at least ten years. Despite a maximum grant allocation per unit of €40,000, just 7 houses have been signed nationally out of a target of 800 by the end of 2017, and none have yet been completed and handed over to a local authority. Between planning levies and building control regulations procedures introduced in 2014, up to half of the current grant allocation goes towards red-tape, statutory permissions and planning levies. In Ireland, building control permissions can take 100 days and cost €7,600 for a small change-of-use conversion. The equivalent building control procedures in the UK take one tenth of the time and cost £695.

No primary legislation is required to rationalise these ‘ad hoc’ regulatory processes in Ireland.

Is Part V Social Housing affordable?

Under current planning legislation, 10% of all schemes of ten or more units must be social housing for sale to local authorities at a discounted price, or on long-term lease terms at discounted rental levels: so-called ‘Part V’ social housing. As part of revised requirements introduced in 2016, developers must provide detailed cost breakdowns for the social housing element with planning applications.

The first residential planning application on Strategic Development Zone land in Cherrywood for 322 units was lodged recently. The Part V social housing submitted was offered to the council to purchase at €354,000 per unit. If this was a new home for sale in the private sector it would require a combined household income of €91,000 to purchase. In contrast, on 29 November 2016 in the Dáil, former Minister Coveney confirmed that the average building costs for conventional local-authority- directly-procured three-bed homes in Co Dublin was €205,250. The overall Cherrywood development site is nevertheless earmarked to receive more than €15m in LIHAF funding.

Conclusion

The Development Contribution Rebate Scheme has proved to be ineffective and may result in a small subsidy to a few hundred single person units in the Fingal and South Dublin County Council areas. Similarly the ‘Repair and Leasing scheme’ has not worked to date and no homes have been completed and handed over to local authorities. LIHAF infrastructure funding sounds impressive, but spread over the next five years it will most likely be administered by the next government not the current one. If LIHAF grants are passed on in full to purchasers this represents less than a 1% discount on sales price per dwelling – this is the equivalent of three weeks of current sales-price inflation. Discounted Part V privately provided social housing in South Dublin is now technically unaffordable, being 70% more expensive than local authority housing in similar suburban locations. Currently there is no affordable housing scheme, no intention by the Department of Housing to introduce one, no definition of what an affordable house is, and legislation underpinning the previous scheme (removed in 2011) has been rescinded. For typical families earning average salaries, options are very limited at present, and affordability will continue to deteriorate in this policy vacuum.

Maoilíosa (Mel) Reynolds is a Registered Architect and Certified Passive House Designer