By Sinéad Pentony

Health is life-defining. We all experience ill-health during our lives and need health services. Health inequalities are reflective of injustice and inequality in society. Austerity has exacerbated this injustice and deepened these inequalities in Ireland.

Three studies have recently been published which examine the impact of austerity on access to health services and the impact of geography on cancer survival rates. A common thread through the research studies is inequality – of access to health services and of health outcomes in cancer survival rates. Health inequalities refer to the differences in the experiences of health among different sections of the population. Although some people will live longer healthier lives due to genetic or hereditary factors, health inequalities refer to inequalities which are unnecessary, unjust and avoidable, and could be addressed through public policies.

The European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions research on ‘Access to Healthcare in Times of Crisis’ found that the economic crisis has had a negative impact across Europe on access to healthcare services not only because of budget cuts, but also because access to healthcare for households has been reduced when their disposable income has declined, creating new barriers to diminished health services. In Ireland, the ESRI budgetary analysis has previously illustrated the disproportionate effect of successive austerity budgets on low-income families, which are also particularly dependent on the public health system and therefore most affected by cuts in health services. The situation in Ireland thus presents a particularly acute case in the European context.

The funding of the Health Services Executive (HSE) was reduced by €3.3 billion (22%) over a four-year period, 2009-2013. Health staff levels have been cut by approximately 10% since the 2007 peak. The health system was able to ‘do more with less’ to a certain extent in the early years of the cutbacks. However, in more recent years it has been more a case of ‘doing less with less’. This is evidenced by the growing numbers of people on trolleys in emergency departments, increased waiting times for public appointments, and the removal of medical cards from significant numbers of people.

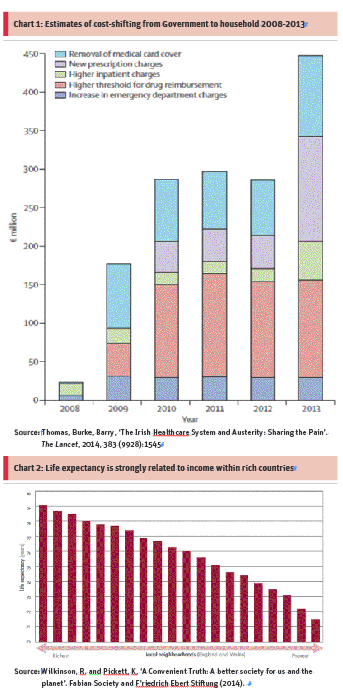

Alongside this there has been a growing trend towards cost-shifting by Government to individuals and families through the introduction of, or increase in, charges and thresholds for reimbursements (illustrated in Chart 1). In 2013, cost-shifting meant that on average every person in Ireland was paying about €100 in additional costs for care and prescribed drugs (Lancet, 2014). This cost-shifting further worsens the inequities in access to health services by low income families.

Budget 2015 included a slight improvement in Government funding for health, which was increased by just over €300 million. This brought the health budget up to €13.1 billion. While this modest augmentation is to be welcomed, Ireland has a growing and ageing population and the additional resources are likely to be eaten up by increased demand for existing services. This leaves little or no scope to extend and improve health services.

The latest OECD data show that Ireland’s total health spend was 8.9% of GDP in 2012. This was the second lowest in the EU (15), which had an average total spend on health of 9.9% of GDP.

This mix of public and private resourcing of health services has resulted in a dual system which means that health services can be assigned on the basis of medical resources (i.e. health insurance) and not medical need.

A funding model that supports a single-tier healthcare system capable of providing universal access is long overdue. The Government had planned to reform the funding of health services and address the inequities in the system through Universal Health Insurance (UHI). While it is questionable whether these goals could have been achieved through the model proposed by the Government, its planned introduction has now been shelved indefinitely. It appears that the Government has gone back to the drawing board in seeking to develop a sustainable funding model.

In the meantime, low-income individuals and families with limited means will continue to face barriers to access to health services, while others continue to skip the queue and receive treatment and care in a timely manner. For some reason it has been accepted that treating patients on the basis of their ability to pay instead of medical need is acceptable in Ireland. Perverse incentives are hard-wired into the health system and will only be addressed through root and branch reform.

The current system of healthcare is a contributing factor to the prevalence of health inequalities, and research projects from the National Cancer Registry (NCR) and NUI Maynooth clearly illustrate the effect this is having on cancer patients living in deprived communities. There have been many advances in the early diagnosis and effective treatment of cancer in recent years; however, these improvements do not always reach the population in the same way.

The NCR research shows that people living in deprived areas experience a poorer survival from cancer than those who live in more affluent parts of the country and it found that breast-cancer patients from the most deprived areas were about 30 per cent more likely to die from their cancer than patients from the least deprived areas.

Those from more deprived backgrounds were more likely to present late with advanced stage cancers and were more likely to present with symptoms rather than present on foot of screening. The research found death rates from cancer in some of the poorest parts of Dublin were more than twice as high as in more affluent areas.

The NUI Maynooth research found that some of these disparities are due to the difficulties getting access to healthcare for the poorest in society. In North Dublin, for example, there is one GP for every 2,500 people. Nationally the figure is 1:1,600. Issues relating to the provision of primary care services are not restricted to towns and cities. The village of Feckle in Co Clare has no GP and it made the national headlines recently when the community offered a rent-free surgery to any GP willing to move to the village.

The equitable provision of, and access to, health services is essential for the elimination of health inequalities. There has been some progress at policy level with the reduction of health inequalities established as one of four goals in the Government’s public-health strategy ‘Healthy Ireland’. However, there is no clear plan on how this goal is going to be achieved, no budget allocation and no targets.

The provision of, and access to health services, is only part of the solution. The main factors influencing health include environment (where we live), education, income and life opportunities. For real improvements in health and wellbeing we need a more equal society. Wilkinson and Pickett (2014) draw particular attention to the very close relationship between life expectancy and income within societies. This relationship is almost perfectly graded across society, as health improves with each step up the socio-economic scale (see Chart 2). This is the pattern of health inequalities which can be seen in almost any society when health is shown in relation to income, education or any other indicator of socioeconomic status.

Reducing and ultimately eliminating health inequalities therefore requires a more equal distribution of wealth, income and resources. This implies investment in public services (including health) and the development of a funding model tahat ensures public-health services are accessed on the basis of medical need. Health is a fundamental human right which can be protected as part of a wider set of economic, social and cultural rights in Irish law.

Enshrining these rights in Irish law would copperfasten their protection and contribute to a more just, inclusive and equal society. •