It covered political patronage, the radical left, industrial disputes, housing campaigns, company closures and sprawling, corruptible Dublin – Brian Trench

Hibernia, for nearly thirty years, was a Catholic publication, one of many in Ireland in the mid-20th century. For its last twelve years, up to 1980, Hibernia was a secular, dissenting voice in Irish media and it is in this guise that it is most often recalled.

The magazine is also remembered as irritatingly difficult to define. In his recently-published history of Ireland in the 1970s, ‘Ambiguous Republic’, Diarmuid Ferriter relies as heavily on Hibernia for information and comment as on any other Irish media. But even as he acknowledges Hibernia’s distinctive contribution, he distances himself from its “strident tone” in relation to republicanism and Irish unity.

Hibernia has in its own time and since been described as “a cross between the Good Wine Guide and Republican News” (Conor Cruise O’Brien), “liberal and sometimes radical” (Vincent Browne, Sunday Independent), “irreverent”, “eclectic”, “crusading” and “investigative” (John Horgan, ‘Irish Media – a critical history’) and “much-loved” (Ranelagh Arts Festival programme, 2006).

All of these labels – and several more – fit at least part of what Hibernia represented from the late 1960s. Its business coverage was targeted at stock market players and its extensive books and arts coverage at the cultural elite, though these sections were also characterised by a restless unwillingness to take the relevant authorities at face value.

John Mulcahy became a regular contributor to Hibernia’s business pages in the mid-1960s. The monthly magazine had needed several injections of funds to keep it going and when editor Basil Clancy could no longer sustain the effort, Mulcahy bought the company.

He brought in young graduates as reporters and section editors, recruiting them more for their curiosity and their critical acumen than for their journalism skills. Many regular contributors, particularly on cultural topics, survived from Clancy’s Hibernia to Mulcahy’s. But as a fortnightly from October 1968, Hibernia sold itself more and more on its critical take on current affairs.

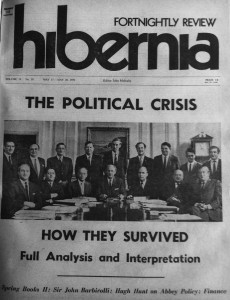

Uniquely for that time, Hibernia published multi-page investigations of social and political topics and provided a platform for a wide range of radical views. Through bold headlines and strong front-page graphics, Hibernia presented angles on the topics of the day largely ignored in other media. It constantly reminded its readers of the injustice inscribed into the Northern state and it decried many of the Republic’s responses to the deepening crisis.

Hibernia’s efforts in this regard and the sensitivities raised are illustrated by the edition of 24 September 1976, whose powerful front page bore the headline: The Strasbourg Report – the men behind the torture. Inside, a short statement was printed on otherwise blank facing pages that the magazine’s printer, The Irish Times, had advised that it would not print the material for those pages because they considered it defamatory.

Reporter Jack Holland had access to affidavits of prisoners mistreated by the RUC and he named individual police officers in the unprinted article. The thrust of his piece was supported by a subsequent judgment of the European Court of Human Rights. But the mainstream media in the Republic were not exploring the conflict in this detail.

Precisely because it was better-informed in this regard than the daily and Sunday newspapers, Hibernia also published critical accounts of republican-movement activities, notably the factional wars, and the blundering efforts of republicans to develop coherent political strategies.

Political patronage, the radical left, industrial disputes, housing campaigns and company closures all received more extensive coverage in Hibernia than elsewhere. Edition after edition, there were stories arising from the largely uncontrolled spread of Dublin city over most of the county. Twenty years before tribunals on the subject were mooted Hibernia reported flagrant conflicts of interest among councillors and hinted at corruption. It pursued named developers for illegal demolitions and many other planning-law breaches.

In 1978 Hibernia moved to weekly publication and production was taken in-house. It soon became evident that Hibernia could not carry the heavier overheads. By this time, In Dublin and Hot Press were competing for younger, culturally curious readers and Magill was doing longer-form political and investigative journalism in an attractive full-colour magazine format.

Dealing with frequent libel actions and threatened actions was an additional load and in 1980 Hibernia closed. John Mulcahy became editor and shareholder in the first version of the Sunday Tribune and the editorial and production staff moved over to the new paper. In the 1980s New Hibernia was published for a short period. But the media and political contexts had changed. Hibernia had run its course when it closed in 1980.

Brian Trench was a Hibernia journalist, 1973-78. He is contributing a chapter on Hibernia to a forthcoming book on 20th century Irish periodicals.