We are now witness to a pervasive acceleration in the normally glacial processes of geopolitical rebalancing in the West. Behavioural economics is helpful in analysing it.

On his first full day in the White House, President Trump signed an executive order withdrawing the US from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the core international economic legacy of the Obama Administration. The TPP, alongside its Trans-Atlantic brother, the TTIP, both trade deals, is also the most public embodiment of the elite-driven obsession with promoting political globalisation under the guise of free trade.

Almost at the same time, a series of political opinion polls across the EU produced historically unprecedented results, showing a dramatic shift away from the mainstream Centre-Left political parties towards the populist parties of the more extreme Left and Right.

In the Netherlands the Labour Party, traditional mainstream leader of the Left, has fallen in popularity to eighth place. To put this into perspective, since the end of WWII, it has never fallen below second place in any general election.

Germany set September 24 as general election date, just as the German constitutional court ruled against banning the neo-Nazi National Democratic Party (NPD) from contesting elections. A milder and more successful version of NPD, the nationalist Alternative for Germany (AfD) is now represented in 10 of Germany’s 16 state parliaments and, with 13-15 percent support among the German electorate, is set to get into the federal Parliament, come the September election.

In Sweden, the centre-right opposition is gearing up for September 2018 elections. Sweden is currently led by a centre-left minority Government that is being challenged by the traditional centre-right opposition parties through an uneasy informal alliance with the far-right Sweden Democrats. The marriage – which is ideologically not quite made in heaven – is a necessary compromise for the traditional right, as the Sweden Democrats are quickly emerging in polls as the biggest political force of the right.

In Austria, the far-right Freedom Party (FPO), a member of the Europe of Nations and Freedom block of EU right-wing and far-right parties, is currently leading the polls with 33-34 percent support, while the Social Democratic SPÖ-S&D are languishing in second place with 27-28 percent support.

In Greece the most recent public opinion tallies put New Dawn at 33-36 percent, well ahead of Syriza with 20-22 percent.

What in January France’s Marine Le Pen called the “European Awakening” is now turning into a tide of popular discontent among the previously solidly centre-left and centre-right voters.

Welcome to the Age of ‘Fu&k You!’ voters.

It’s the Uncertainty, Stupid

In reality, despite all the mainstream media’s attempts to argue to the contrary, the rise of populism in the US and Europe is neither new, nor unexpected. And, as in the US, that rise is firmly anchored in behavioural economics. More precisely, it is grounded in the growing chasm between the rhetoric of free trade, free markets and economic empowerment presented by centrist politicians and technocrats, and the reality of a corporatist takeover of the Western democracies that has led to an unprecedented increase in socioeconomic uncertainty in the lives of ordinary men and women.

Consider the key signposts. For decades, behavioural economists have known that people make choices under conditions of uncertainty differently from when facing risk.

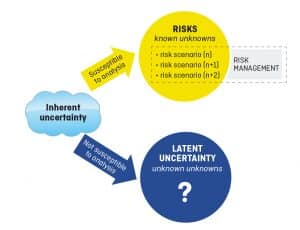

First, people are more prone to eschew uncertainty, as opposed to avoiding risk. In simple terms, this means that we tend to focus more intensively on the potential negative effects of choices made in an uncertain environment, than when we are facing the same decisions in the presence of mere risk. For those unaware of the differences, risk refers to a situation where the potential outcomes of a gamble may be uncertain, but are known or are governed by a known probability distribution. In contrast, uncertainty occurs when we do not know all possible outcomes of a gamble in advance and cannot assign a particular probability distribution to those we do know.

Second, the effect of uncertainty on our decisions is magnified by our past experiences. When losses have dominated our experience of past choices, future choices under conditions of uncertainty can lead to the acceptance of more risky gambles, while past wins tend to decrease our willingness to take risks.

Whether or not you trust the official growth and employment statistics coming out of the US and other Western economies today does not matter. The salient points are how much uncertainty does the current socio-economic system generate and whether the voters are aware of the changing nature of uncertainty. Here, we have helpful data: the Economic Policy Uncertainty Index, which measures the degree of policy uncertainty encountered in the national and international news media.

Between 1994 and 2008, Economic Policy Uncertainty in Europe, UK and the US tended to move within a similar and largely moderate range. In other words, with the exception of when the dot.com bubble burst in 2001-2002, there was little deep uncertainty about the direction of economic policies in the West. Even at the inception of the Global Financial Crisis, economic policy uncertainty was of relatively low concern for the news media.

The Seas of Policy Tranquillity were the golden area of pre-2009 economic statism: Social Partnerships-styled corporatist politics assured industrial peace in exchange for the financial bubbles- and debt-funded spread of prosperity. This tranquility was shattered around 2009-2010, when the European Sovereign Crises took hold.

As shown in the chart above, since then economic policy uncertainty took hold in Europe and the UK. In 2016, this crisis became systemic: following the Brexit vote, the UK’s economic Policy Uncertainty Index ended 2016 with an average annual reading of 562 – an all-time high and dramatically up on the 324 reading for the peak of the European Crisis period in 2012. In Europe, EPU also posted its record reading at 288, up on the previous all-time record of 222 in 2012. Even with its November 2016 election, the US EPU averaged 167 in 2016, still below the 180 readings recorded in 2011 and 2012 and below 2001 reading of 173. However, US EPU is now also firmly on an upward trend.

This record-busting uncertainty follows a decade-long (and, in the case of economies like Italy, decades-long) near-zero growth environment for middle class incomes, and a jaw-busting redistribution of wealth and income in favour of the capital-rich elites.

In simple terms, for an average voter in the West, today’s decisions take place in the environment of historically high uncertainty and continuously cumulating past losses of wealth and income. Behavioural economics tells us that the voters are likely to back increasingly riskier alternatives amongst those on offer, while (to-date) winning elites are more prone to defend the status quo, avoiding taking risks. Sounds familiar? Just think Hillary Rodham Clinton v Donald John Trump.

In the Long Run Betrayal Costs, dearly

But there is an added behavioural insight into the developing trend.

Almost 14 years ago, two behavioural economists, Jonathan J Koehler, and Andrew D Gershof, defined another behavioural phenomenon, known as betrayal aversion. Specifically, the authors stated that: “A form of betrayal occurs when agents of protection cause the very harm that they are entrusted to guard against”. The authors then showed, experimentally, that people respond differently to various acts of betrayal of trust depending on who acts as an agent of betrayal. Specifically, people react “more strongly …to acts of betrayal than to identical bad acts that do not violate a duty or promise to protect”. How differently? “Apparently, people are willing to incur greater risks of the very harm they seek protection from to avoid the mere possibility of betrayal”.

In every election, voters vest their trust in a candidate for office on the basis of the candidate’s policies platform and promises. They do so to maximise their own well-being or to avoid harm from alternative candidates’ policies. The basic relationship between the voters and the candidate is emotionally-framed. Worse, the relationship of trust induces the feeling of betrayal if the candidate does not deliver on her or his promises. Finally past experience of betrayal, quite rationally, induces a betrayal aversion reaction: at some point in time, voters will throw their support for a candidate who offers less in terms of her or his platform quality in order to avoid being betrayed by a smarter candidate. All in, betrayal aversion will drive voters to prefer a poorer quality candidate.

President Obama’s failure to deliver on his promise of hope, so widely embraced by the US voters in 2008 and subsequently in 2012 was nothing less than a betrayal for a large number of the American voters. This betrayal was made more acute by the emotional nature of the Obama campaigns. And, in the 2016 election, of the two main candidates contesting support from the swing and marginalised voters, one – Hillary Clinton – stood for the continuation of the Obama legacy, the other – Donald Trump – stood for its repudiation. In the end, Clinton lost precisely because, being the candidate of the betraying agency of the status quo, she offered a more developed, lower-risk-policies platform.

This stunning conclusion has been worked out theoretically and supported empirically by two researchers from Harvard University: Rafael Di Tella and Julio Rotemberg in their December 2016 NBER paper. The authors argue that voters’ preference for populism is the form of “rejection of “disloyal” leaders”. To do this, the authors add an “assumption that people are worse off when they experience low income as a result of leader betrayal”, than when such a loss of income “is the result of bad luck”. It was not the ‘deplorables’ of Trump’s camp but the middle class marginal voters betrayed by Obama who swung the electoral college in favour of a populist.

Learning Before it is Too Late

This all brings us to the lessons that European leaders must learn before the next round of the general and European elections: to avoid a replay of the US presidential contest, Europe desperately needs to break the vicious cycle of voters’ betrayal at national and EU levels. It also needs to drastically stem the rising tide of policy uncertainty.

I believe both objectives can only be achieved by grounding the EU in the reality of what has been happening on the ground, in the member states, and putting a full stop to the relentless march of the European technocracy toward greater political integration and continued advancement of the economic status quo. The death call for TTIP coming from Washington is as good an opportunity to do this as Europe will ever get. Instead of continuing to insist that the state-corporate consensus (exemplified by TTIP) is the path toward a better future for European citizens, Brussels, Frankfurt and national governments across the EU should focus on scaling-back European institutions to their original core functions: supporting freedom of trade, free capital mobility and freedom of movement for the block’s citizens. The energy saved would allow concentration of scarce political and economic resources on strengthening commitments to these basic principles of the Union. But it also could allow European states to focus on the need to develop new policies to advance their citizens’ interests – a reorientation that is necessary for the reconstruction of voters’ political trust.

By Constantin Gurdgiev