By Sinéad Pentony

Remember the Spring Statement? Mainstream commentary reassured us that it was ‘prudent’, ‘getting the balance right’, providing ‘clarity’, ‘breaking with the policies of the past’ and ‘anchoring expectations in forecasts’. Some just suggested ‘nothing has changed’. Then silence. It was of course a political exercise but fundamental questions raised by the Spring Statement got little attention.

In terms of process the Spring Statement is a welcome development. The macro-economic goals are set out and the detail on how these goals will be achieved is the business of the October budget. Previously, this was done in reverse, with deals then being done with various interest groups, which were added up to become the macro-economic goals.

The Government’s “intention to examine the possibility of establishing of an Independent Budget Office” is also welcome. This Office would allow for independent costings of policy proposals from all political parties and Groups in the Oireachtas. The Office of Budget Responsibility in the UK and the Parliamentary Budget Officer in Canada are both good examples of how such an office can contribute to evidence-based debate on the budgetary choices about taxation and expenditure. It would have been reassuring to get something more than an “intention”, however, and it remains to be seen if it will materialise.

Most of the criticism focused on the ratio between taxation and expenditure measures. The forthcoming budget will see a modest expansion of €1.2bn to €1.5bn that will be split 50:50 between expenditure and taxation measures. More of the same can be expected in the following years if growth forecasts of 3-4% are realised. The underlying assumptions associated with the growth forecasts and the impact of external factors including low oil prices, a low-interest-rate environment and weak euro, the combination of which have reduced costs and increased competitiveness were also a focus for criticism.

However, it is the trickle-down model of development that should have been the focus for criticism. “Policies for Growth” is the dominant section. Six policies are identified as growth drivers including: a growth-friendly tax system; access to finance for SMEs; labour market policies; recouping the cost of the bank bailout; reducing the drag from public debt; and targeted sector specific intervention. Sound macro-economic policies are a pre-condition for sustained growth, employment and poverty alleviation. However, focusing exclusively on growth and assuming that its benefits will automatically trickle down to different segments of the population may undermine growth in the long run. This is one of the findings from new research from the OECD: ‘In it Together: Why Less Inequality Benefits All’.

The OECD research points to the importance of carefully assessing the potential consequences of pro-growth policies on inequality. It also indicates that policies aimed at helping to limit or, ideally, reverse the long-run rise in inequality would not only make societies less unfair, but also richer. The central argument in the report is that, beyond its serious impact on social cohesion, high and often growing inequality raises major economic concerns, not just for the low earners themselves but for the wider health and sustainability of our economies. Put simply: rising inequality is bad for long-term growth.

Addressing the multidimensional nature of inequality and its impacts on different segments of the population, therefore, matters for sustainable economic growth. Inequalities arise for income, educational attainment, health conditions and employment opportunities. All of these have become important determinants of growth and wellbeing. “Inclusive Growth” is a new approach to economic growth that aims to improve living standards and share the benefits of increased prosperity more evenly across social groups.

Fostering “Inclusive Growth” is an important part of a pro-growth agenda and the OECD research identifies four main policy areas where action is needed: women’s participation in economic life; employment promotion and good-quality jobs; skills and education; and tax-and-transfer systems for efficient redistribution.

First, though gender gaps in employment and earnings have declined, they remain large and there is a need for policies to eliminate the unequal treatment of men and women in the labour market. Policy solutions include affordable and high-quality childcare; changing the dearth of women in senior positions; measures aimed at reconciling work and family life; and measures aimed at reducing the concentration of women in jobs that are less valued and are paid less.

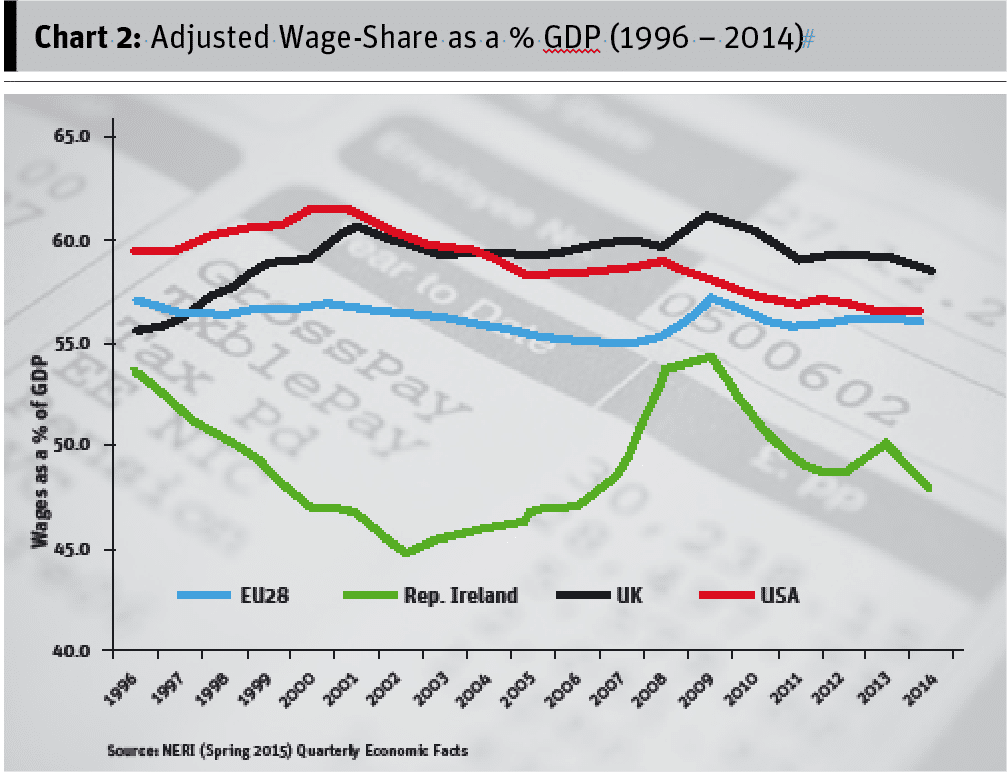

Second, there is a need for more inclusive labour-market policies which focus not only on the quantity but also on the quality of jobs. This requires a focus on earnings; job security; and the quality of the work environment. In Ireland, low pay is a significant issue in the labour market and is concentrated by gender and in certain sectors of the economy such retail and hospitality. The lowest earners lost proportionately more of their income over the five-year period 2008-2013 than all other income groups (see Chart 1).

Research from NERI (Quarterly Economic Observer, Spring 2015) shows that a quarter of employees earn less than the Living Wage threshold of €11.45 per hour and almost a third (30%) earn below the EU low-pay threshold of €12.20 per hour. The newly-estab

lished Low Pay Commission will have an important role to play in raising the wage floor. There also needs to be focus on illustrating the contribution of wage-led growth to greater equality and inclusive economic growth.

The quality of the work environment can be improved by strengthening the rights of workers through collective bargaining and the introduction of legislation on the right to collective bargaining. This will hopefully start the process of reversing the trend toward precarious low paid employment.

Thirdly, lack of investment in skills and education is a key transmission mechanism between inequality and growth. While there is always a gap in education outcomes between individuals with different socio-economic backgrounds, the gap widens when people in disadvantaged households struggle to get quality education. This implies large amounts of wasted potential and diminished chances of improving standards of living and quality of life. In particular, low-skilled temporary workers face substantial wage penalties, earnings instability and slower wage growth. This should be reversed.

The lack of investment in a comprehensive early-years education system and the impact of budget cuts to education in general over the last number of years are likely to have made it more difficult for people to use education as a route out of disadvantage. The OECD Skills Outlook 2015 found that Ireland was the fourth lowest out of 22 OECD countries for average numeracy and literacy proficiency among young people aged 16-29 years-old in 2012.

The fourth area of an effective policy strategy to balance more equality with economic growth relates to taxes and transfers. These policies constitute the most direct and powerful instrument to redistribute income and most countries make substantial use of income taxes and cash transfers to reduce income gaps. At the same time, the OECD has also found that public expenditure tends to lower inequality and increase economic growth.

The Government has signalled its intention to reduce taxation measures related to labour and marginally increase public expenditure in the Spring Statement. Ireland’s tax take in 2013 was 34.8% of GDP, compared to the EU average of 45.3%. Ireland’s public expenditure in the same period was 40.5% of GDP, compared to an EU average of 48.5%. While the tax base has been broadened, much more could be done to eliminate or scale back tax deductions, which tend to benefit high earners disproportionally, and to reassess the role of taxes on all forms of property and wealth, including the transfer of assets.

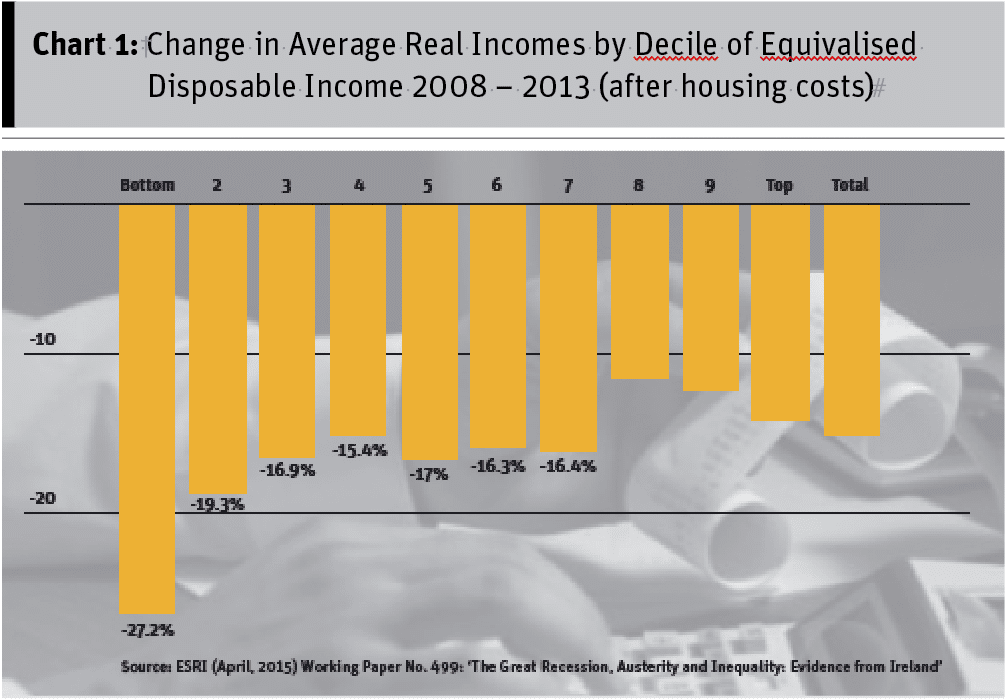

This is particularly important in Ireland, where the share of wages continues to decline as a proportion of our total income. In 2014, the wage share in Ireland was 48% of GDP, compared to the EU average of 56.3% (see Chart 2). Multinationals must also pay their fair share of tax. It appears that measures aimed at increasing transparency and international co-operation on tax rules to minimise “treaty shopping” will be introduced at EU level in due course.