In January 2017 the Historical Institutional Abuse Inquiry (HIAI) reported on the treatment of children in care in Northern Ireland. The Inquiry, chaired by Sir Anthony Hart, conducted its extensive task with considerable speed and reported on the day of President Donald Trump’s inauguration. The Inquiry shared something else with the then incumbent US president, a reluctance to process unwelcome information.

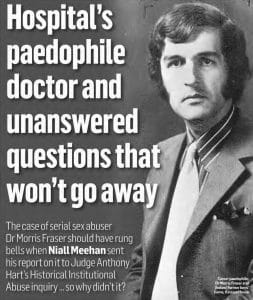

The Inquiry ignored evidence that from 1971- 73 an accused and then convicted serial child-abuser named Dr Morris Fraser continued to work with vulnerable institutionalised children. The HIAI also refused to examine how and why police protected the internationally-known child psychiatrist from exposure and from professional censure, for a year after he was found guilty of abuse.

The HIAI was asked to make recommendations and findings concerning institutional failings with regard to children in the care of the state and/or of its agencies. It was tasked also with indicating if failings were systemic. The HIAI failed to do so in the case of Morris Fraser.

This is more than merely a story of out-of-date attitudes and of the embarrassing proclivities of wayward medical folk. It concerns something officially rotten in the state of Northern Ireland in 1972, that a public inquiry in 2016 felt unable to scrutinise.

The HIAI Report, chapter 26, page 82, briefly considered and then dismissed discussion of Fraser’s work and of his official treatment. It found that:

“… the way the medical authorities and the police dealt with Dr Fraser after his [May 1972] conviction in London are not matters that fall within the Terms of Reference of this Inquiry and we have not considered them”

The finding was based on the Inquiry’s view that Fraser’s interaction with institutionalised children was peripheral to his main work with outpatient children. Volume seven of the HIAI Report dealt with Lissue Hospital’s in-patient child psychiatric unit, where abuse allegations were rife. Chapter 24, page 22, paragraph 84, stated:

“It is probable that Dr Morris Fraser worked at Lissue Hospital as a Senior Psychiatric Registrar in the course of his training”.

This is followed by error-strewn commentary on Fraser’s 1972 child-abuse conviction in the UK and, two years later, in the US. The HIAI stated that “Dr Fraser was convicted again of sexual offences against a child in New York in May 1973”. In fact, Fraser was convicted in June 1974 of abusing three boys, not one. He was merely arrested in May 1973. The complacent commentary concluded in paragraph 87 with:

“Dr Fraser continued to work elsewhere as a psychiatrist, though not with children, and he then took early retirement”.

In fact, the four-times convicted paedophile abused children and associated with abusers until he was persuaded to remove himself from the medical register in November 1995. Fraser made use of his medical status to groom children for his own use and for the benefit of other paedophiles. Paragraph 87 began, “there is no evidence of Dr Fraser’s work at Lissue…”.

These nothing-to-see-here findings were partially based on 13 April 2016 testimony from Dr William Nelson at HIAI hearings. He was the first director of the new Lissue children’s psychiatric unit, that opened in 1971. Under remarkably brief and light questioning, Dr Nelson suggested, from memory, that Fraser might have been at Lissue for “a short time”, but that his “main work” was over 10 miles away, at the Royal Victoria Hospital “in out-patients”.

There are two issues of concern.

The first involves documentary evidence, in the HIAI’s possession, querying Dr Nelson’s recollection of events over four decades earlier. The HIAI ignored the documentation. The second relates to how Dr Fraser came to perform clearly established duties in Lissue, even though he was simultaneously (unbeknown to colleagues) a convicted paedophile offender. I will deal with each issue in turn.

Some Background

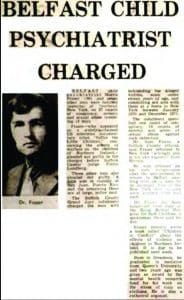

The reason for the HIAI’s curiosity about Fraser is because, on 17 May 1972 at Bow Street Magistrates’ Court Dr Fraser pleaded guilty to having sexually abused in London in August 1971, a 13 year-old Belfast boy. Fraser had brought three boys from Belfast to London, ostensibly on a scouting trip. Fraser was conditionally discharged with a £50 fine and was bound over for three years. His co-accused, Ian Bell, whose case was considered separately. Bell pleaded not guilty at Bow Street to abusing a 10-year-old, and went on to Crown Court, where he was convicted after changing his plea.

As is the case today, in 1972 police could either hide from, or present to, the public, an accused person and the crimes with which they were charged. In this case an internationally-known child psychiatrist was processed through a court late in the evening, after 9pm, without anyone noticing. Fraser started giving off signs of being an officially protected species of paedophile.

Inexplicably, Dr Fraser continued to see children in the Royal Victoria Hospital, and to enjoy a prominent newspaper, radio and television profile in Ireland, Britain and the US. That is because police did not tell the NI Hospitals Authority, Fraser’s employer, of his abuse conviction.

One year later, in May 1973 on the other side of the world, Fraser was stopped temporarily in his tracks. He was arrested in New York as part of an eight-man child abuse ring. Unlike Fraser’s effectively secret October 1971 arrest and May 1972 conviction, his 1973 New York arrest was covered in the US, followed by British and Irish, news media. In February 1974 in Suffolk County, NY, Fraser’s guilty plea, to abusing three boys, was reported briefly in the New York Times. Fraser was convicted in June 1974 and was again conditionally discharged. Disturbingly, the judge was not informed of Fraser’s 1972 London conviction. Fraser’s US conviction and subsequent deportation were ignored by news outlets. Fraser should have been, but was not then brought back before a UK court, having broken the terms of his May 1972 three-year ‘conditional’ discharge.

The HIAI ignored all of this because it said that Fraser worked with outpatient children and not with those institutionalised in Lissue Hospital’s psychiatric unit.

1. Fraser’s Work at Lissue

Let us consider Lissue, where the HIAI found “no evidence”of Fraser’s work.

In September 2016 the General Medical Council (GMC) gave the HIAI two July 1973 letters from Dr William Nelson on the subject of Morris Fraser. Nelson, Lissue’s then clinical director, detailed the role played by Dr Fraser at Lissue during 1972-73.

In its Report the HIAI ignored these letters and other highly relevant GMC material.

The HIAI Report instead drew conclusions about Fraser mainly from the same Dr Nelson’s 2016 recollections. There is no mention whatsoever in the HIAI Report of the 1973 Nelson letters provided by the GMC. The Inquiry preferred instead to rely on the frailty of memory.

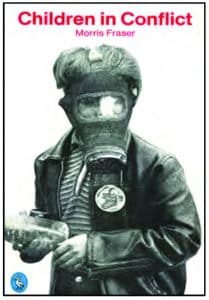

I would like, briefly, to outline some this GMC material. In mid-June 1973, 13 months after his London conviction, the GMC wrote to Dr Fraser and informed him that he was being charged with “serious professional misconduct”. At that stage Dr Fraser obtained supportive references from colleagues, including from the well-known psychiatrist and author, Anthony Storr. He received one too from Secker & Warburg managing director Tom Rosenthal. He had just published Fraser’s ‘Children in Conflict’, recently serialised by the Sunday Times. Rosenthal observed on 16 July 1973 that his “strong interest in psychoanalytical matters” gave him “rather more knowledge of the subject than the average layman”. He further advised the medical personnel evaluating Fraser’s behaviour:

“It is my considered view, and I speak also as the father of two young sons, that none of the events which have caused Dr Fraser to appear before the General Medical Council’s Disciplinary Committee would in any way affect his professional and clinical abilities, and I cannot really say more than were it necessary for me to seek psychiatric help for my own sons, I would be happy to place them in Dr Fraser’s care”.

Fraser’s immediate superior, Dr William Nelson, also provided a supportive letter on 6 July 1973, with a further elaboration on 11 July. In his initial letter Dr Nelson stated:

“Dr Fraser worked initially on an out-patient basis and then in the last year and a bit he worked in our 20-bed in-patient unit [in Lissue Hospital], where there are also 5 day patients…. In both the out-patient and the in-patient units Dr Fraser proved a very capable and conscientious doctor. In both situations he had to work with a number of other disciplines in child psychiatry, such as social workers, psychologists, occupational therapists and teachers.

In his most recent post as Senior Registrar at the in-patient unit, Dr Fraser was given responsibility for the medical management of the in-patient unit.”

This activity, including interaction with social care workers in deciding the fate of institutionalised children, brought Fraser squarely within the terms of reference of the HIA Inquiry.

Far from being a vague probability that Fraser was at Lissue for brief periods, “as part of his training”, Dr Nelson’s 1973 letter confirms that Lissue was where the by-then-convicted offender mainly worked for an extended period.

43 years later, on 13 April 2016, the Inquiry Panel briefly asked the same Dr Nelson about Dr Fraser at Lissue. Dr Nelson said, “He may have been there for a short time. My recollection is that his main work was actually in outpatients”. When asked if he had taken steps to ascertain whether Dr Fraser had acted inappropriately, after abuse revelations came to light in May 1973, Dr Nelson told the HIA, “I didn’t ask or investigate”. Without further ado, the Inquiry then passed to other matters.

Given his supportive 6 and 11 July 1973 letters, written after Dr Fraser’s New York charges and after his London conviction was notified officially to the NI Hospitals Authority, Dr Nelson’s failure to ‘ask or investigate’ seems surprising. Apparently, the HIAI did not find it so.

Dr Nelson, who had a primary responsibility toward children in his care, furnished a second letter on 11 July 1973 for GMC consideration. In it he wrote:

“If the various bodies who look at Dr Fraser’s position decide that he should return to this child psychiatry setting, I myself would accept their decision and have him working back here”.

While it cannot be stated definitively, possibly Dr Nelson’s willingness to accept Dr Fraser “back here” assisted the GMC in reaching a decision in 1975, permitting Fraser to practice without restriction. Perhaps Tom Rosenthal’s quack psychiatry and his eagerness to sacrifice his sons to Fraser’s care assisted also.

The approaches adopted in 1973 display an insufficiently rigorous attitude toward child abuse and indicate important lessons to be learned. At least, they would do if the HIA Inquiry had properly considered them.

Dr Nelson’s April 2016 evidence to the Inquiry displayed understandable forgetfulness in terms of how long Dr Fraser worked at Lissue and his responsibilities there. Of concern is that in September 2016 the HIAI ignored definitive documentary evidence from 1973, outlined here.

That brings us to the second, related, point, also ignored by the HIAI Report. It reveals why Fraser continued to work with children after his abuse conviction. This is, by far, the greater failing.

2. RUC and Metropolitan Police Failings

How was it that a convicted child abuser was appointed to responsible positions in the care of vulnerable Lissue children in 1972 and 1973? Evidence suggests that police inaction, contrary to regulations, was responsible. It points also to deliberate police frustration of GMC attempts to bring Fraser to book.

Dr Nelson and his senior colleagues in the NI Hospitals Authority were not made officially aware of Fraser’s 17 May 1972 conviction in London (which, remember, was not reported in the news media) until one year later, eight days after Fraser’s sensational 3 May 1973 New York arrest. A ‘Certificate of Conviction’ was then dispatched to the Authority, according to an entry in the Bow Street Magistrates’ Court archive. It does not state who sent it.

The responsibility for officially reporting the May 1972 conviction was the police’s: in this case that of the Royal Ulster constabulary (RUC) and the London Metropolitan Police. In May 2016 DCS George Clarke of the Police service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) was given the task of supplying the HIAI with a commentary on a March 2016 26-page report I wrote on Fraser (KIN1812). In it Clarke observed:

“In 1972, prior to the disclosure of an offence to an employer, the Police (including the RUC) had to consider whether an offence ‘may reflect on a person’s suitability to continue in his profession or office’ (Section XVII, Home Office Consolidated Circular 1969). The police were also asked to judge in each case whether the public interest in disclosure justified departure from the general rule of confidentiality. The occupations covered seem focused around those administering state functions; the medical profession, teaching and the care sector (children only), justice professions (magistrates and solicitors) and transport provision (pilots and public service vehicle drivers)”.

Clearly, therefore, Fraser, a medical professional specialising in the care of vulnerable and institutionalised children, was a person whose child-abuse conviction should have been notified to his employer. There seems little doubt that this should have happened.

DCS Clarke’s commentary suggested that notification was a job for the Metropolitan Police. Though Fraser and the 13-year-old he abused were from Belfast, the offence took place in London. However, the initial complaint against Fraser was made in Belfast. The RUC investigated, arrested, and took Fraser’s statement. Clarke’s claim is in any case contradicted by the fact that the NI Police Authority sent a Certificate of Conviction about Fraser’s crime to the General Medical Council on 19 July 1972. In other words Northern Ireland police admitted a role in notifying relevant bodies of Fraser’s conviction. It seems logical that the NI Police Authority should have communicated locally with the NI Hospitals Authority about Fraser.

Remarkably, in 1972 neither the NI nor the London police force sent a Certificate of Conviction to the Northern Ireland Hospitals Authority, though both sent one to the GMC. That is why Fraser continued to treat children as though nothing had happened. Equally remarkably, GMC documents highlighted that the RUC (in particular) spent the following year frustrating and significantly delaying the GMC’s investigation of Fraser. That is why the GMC took until June 1973 to call Fraser to a July 1973 disciplinary hearing. It was not due to the GMC only just becoming aware of Fraser’s activities, as a result of his May 1973 New York arrest (as had previously been thought). It was due to police frustration of GMC attempts to bring Fraser to book.

The RUC refused GMC agents access to “any of the persons involved”, including RUC personnel. A 2 April 1973 letter from the GMC’s legal adviser to the GMC stated:

“The position is that some time ago we instructed Agents in Belfast to assist us with the enquiries but these have been held up due to the lack of co-operation they have received from the Royal Ulster Constabulary there. We ourselves have spoken with the Chief Superintendent in Belfast but regrettably this has had no effect and it has therefore not been possible for our Agents to see either the Police Officers involved or the boy’s mother [name redacted]. Indeed we do not even know the address of this woman and all efforts so far to establish it have proved unsuccessful”.

‘Spinwatch’ Investigation, 31 March 2016

On 15 May the adviser followed up with:

“I regret to report that our agents in Belfast have met with no success in interviewing any of the persons involved in this matter.

The local Police are inclined to be rather uncooperative and for a considerable time refused even to acknowledge our Agent’s letters. They have refused to divulge the address of [name redacted] but the police have apparently interviewed [name redacted] and her son, and they have both indicated that they refuse to assist us or our agents in any way.

In the circumstances we are unable to take this matter any further”.

The RUC assertion that the mother of the abused child did not wish to speak to GMC agents, and the RUC’s refusal to pass on her address is suspicious. She would have been in a position to contradict a police narrative that considerably diminished the scope of Fraser’s crime. She might also have challenged a vicious smear that her 13-year-old son had “corrupted” the otherwise innocent Dr Fraser.

The refusal to send a Certificate of Conviction to Fraser’s employer was eventually rectified, one year late. It was sent to the NI Hospitals Authority in May 1973, one week after Fraser’s publicised New York arrest. In other words, there was a belated (though silent) recognition of a May 1972 failure to inform Fraser’s employer. That failing was covered up in May 1973. It is not as though Fraser was a forgotten about, unnoticed, unknown, doctor. He appeared regularly in newspapers and on radio and television speaking on the care of vulnerable children during the early days of the ‘Troubles’. He was a well-known medical celebrity. It was simply impossible for police to overlook Fraser’s existence.

Whether or not the responsibility for telling Fraser’s employer lay singly with the London police or jointly with the RUC, failure to send it meant that a seemingly blameless Dr William Nelson gave Fraser increased responsibility for the care of vulnerable children in Lissue Hospital’s child psychiatric unit during 1972 and 1973.

Had Fraser been publicly disgraced in or soon after May 1972, it is highly unlikely that he could have used his medical status to abuse US or other children up to May 1973. Responsibility for that serious state of affairs lay with police who effectively kept Fraser’s abuse secret.

The HIAI complained to the UK’s Independent Press Standard’s Organisation about the Belfast Telegraph article, and won on the basis that Fraser was beyond the HIAI’s terms of reference. As this article demonstrates the HIAI withheld evidence that Fraser’s official treatment was part of the Inquiry’s remit. The complaint was made under false pretenses.

The HIAI did not consider this police failure in relation to Fraser. In fact, in June 2016 the HIAI assured retired RUC officer Ronald Mack (who took Fraser’s 21 October 1971 statement of admission to abuse) that it was not investigating police failures in the Fraser case (KIN1777). The HIAI refused this information to me, when I asked for it in August 2016.

The HIAI’s decision was based on its clearly false assumption that Fraser had no role in the care of children institutionalised in Lissue Hospital, and that therefore Fraser’s official treatment was beyond the HIAI’s terms of reference.

Conclusion

Fraser had a role in the care of institutionalised children but the HIAI ignored evidence showing this.

Investigating Fraser’s official treatment was, therefore, within the Inquiry’s terms of reference, contrary to a finding in the HIAI’s report. The HIAI’s behaviour regarding Fraser was very strange indeed, as was its negative attitude to those alleging security-force involvement in the infamous Kincora Boys’ Home.

The information set out above has been communicated to the Stormont Executive Office in Belfast, which is preparing information for ministers on the outcome of the HIAI Inquiry. Necessary corrections to the final report of the HIAI have been requested. It has been sent also to the British Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, James Brokenshire.

Niall Meehan is head of the Griffith College Dublin Journalism and Media Faculty