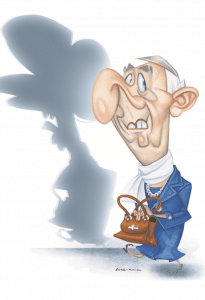

One thing you can’t fault Charlie McCreevy for is his consistency. The palpitations in the world economy might have exposed his allergy to financial regulation as reckless, yet McCreevy’s faith in unfettered capitalism remains undimmed.

Since taking up his post as the EU’s single market commissioner in 2004, McCreevy has repeatedly recited the mantra ‘less is more’. “For far too long the EU has been adopting rules at EU level, simply for the sake of having rules at that level”, he told a conference in Cape Town during 2007. “Once adopted the rules have been left to gather dust on the statute book. My approach is a different one. We should adopt fewer, better quality rules and then devote our energy to making sure they are properly enforced”.

Superficially, this appears like McCreevy has been trying to replace the Euro-twaddle of the Brussels elite with the plain-speaking of Kildare racecourses. The truth, however, is that he has gone to enormous lengths to shield some of the most dubious practices in modern finance from oversight.

During January, The Financial Times described McCreevy’s approach to hedge funds and private equity as “more nuanced” than those of his direct boss, European Commission president José Manuel Barroso. Leaving aside that this may be the first time the word ‘nuanced’ has been applied to anything advocated by McCreevy, the FT claim is untrue. McCreevy has maintained that hedge funds should be subject to no more than voluntary codes of conduct. He has, however, been pressurised by Barroso into drawing up plans for binding regulation so that they can be formally proposed ahead of the European Parliament elections in June. By arguing that hedge funds can manage themselves, McCreevy is out of sync with a growing body of international opinion.

Barack Obama’s nominee as Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner has signalled that he is in favour of mandatory registration and surveillance in this field. So, too, have Angela Merkel and Nicolas Sarkozy.

He has an extremist position and is a full believer in the casino style of capitalism that has now collapsed.

McCreevy has maintained that hedge funds play a largely positive role, ignoring how they helped trigger the sub-prime crisis in the US and how they have engaged in shortselling banks on this side of the Atlantic. “I think he is finding it very hard to accept that his beloved unregulated market has failed”, said Poul Nyrup Rasmussen, the former Danish prime minister and now a Socialist MEP. “He has certainly been trying to delay and where possible avoid regulation on hedge funds and private equity. I can’t say what lessons he has learned from the crisis but he does not seem to have changed his dislike of market regulation which is a pity because practically everyone else has realized that better regulation is unavoidable and necessary. I suspect we will encounter further efforts by him to put off regulation”.

Some clues as to why McCreevy remains so convinced of the virtues of hedge funds may lie in time in domestic Irish politics. Although hedge funds were banned in Germany until 2004 because their speculative activities were considered too risky, McCreevy had no qualms about welcoming them to Ireland as the country’s finance minister. And by the time their global value was estimated at $2.5 trillion last summer, the IFSC in Dublin stood alongside London and New York as one of the major onshore centres of hedge funds in the world. “Mr McCreevy behaves like a lobbyist for the hedge fund industry,” says Peter Wahl from World Economy, Ecology and Development (WEED), a German anti-poverty group. “He has an extremist position and is a full believer in the casino style of capitalism that has now collapsed”.

Once dubbed the most right-wing finance minister in Europe by Proinsias de Rossa, McCreevy has used his platform as a commissioner to identify with the chief architects of market fundamentalism. While his ideological preferences were never really in doubt, he nonetheless chose December 2005 as his ‘coming out’ month. He praised Margaret Thatcher for how she had “economically transformed” Britain. And he quoted Milton Friedman, intellectual guru to Ronald Reagan and Augusto Pinochet, to support his contention that tax competition between nations is healthy. Again, McCreevy finds himself marginalised in holding that view.

In December last year, a UN conference in the Qatari capital Doha recognised the kind of tax competition McCreevy favours as a major contributor to global poverty. Obama has also promised to crack down on tax havens. According to the World Bank up to $800 million in untaxed capital leaves poor countries or economies in transition each year, frequently because multinational firms have received tax breaks from the host countries. This dwarfs the $100 billion that such countries receive in annual development aid.

Accountancy firms have provided invaluable advice to companies about how they can conceal their profits and thereby evade tax. The four biggest firms with global reach – PricewaterhouseCoopers, KPMG, Ernst & Young and Deloitte – have all paid huge settlements in recent times after they were sued for breaching financial rules. Yet they have a staunch ally in McCreevy, himself an accountant by training, who has recommended that the four (joined together in the International Accounting Standards Board) should effectively set the rules that companies listed on the EU’s stock exchanges should follow.

This has thwarted moves to introduce the kind of international system that is needed to tackle tax evasion: one where every multinational firm has to state what profits it makes and what taxes it pays in every country where it operates. “Published accounts will always be like bikinis – much more interesting for what they conceal than for what they reveal”, McCreevy has said. “The view that more frequent reporting by companies increases transparency is one about which I am deeply sceptical”.

Despite speaking about opaque financial transactions in colourful and accessible terms, McCreevy has snuggled up to a largely unaccountable corporate elite. “The IASB is a private company,” said John Christensen from the Tax Justice Network. “By and large, it is manned by and controlled by the big four accounting firms and their clients. It doesn’t generally consult outside the four. McCreevy is very closely connected to the four, he comes out of that background. And he doesn’t buy into the idea that there is a legitimate interest in corporate information outside the investor community.

“There are not necessarily any financial conflicts of interests. But I’m afraid McCreevy is seen as representing the interests of the International Financial Services Centre in Dublin. Dublin is competing with other tax havens like the Isle of Man and Jersey. It is pushing lax regulation and McCreevy is seen as part of that problem of lax regulation”.

For his own sake, it’s probably just as well that McCreevy has ruled out seeking a second term in Brussels. Although the European Parliament rarely gives designated commissioners more than a verbal grilling at confirmation hearings, there is a widespread (if admittedly academic) feeling that his re-appointment would be strongly contested by left-leaning MEPs, many of whom regard him as the most objectionable member of the current Commission.

One of his most egregious displays of neoliberal arrogance came during a 2005 visit to Sweden. There, he publicly supported the Latvian construction company Laval over its demands that its operations in Sweden should not have to respect the country’s agreements on pay and working conditions.

His re-appointment would be strongly contested by left-leaning MEPs, many of whom regard him as the most objectionable member of the current Commission.

McCreevy subsequently described it as “extraordinary” that he should have to face questions in the Parliament, when he was simply upholding the primacy of competition over such pesky issues as worker’s rights. But he was not sufficiently chastened by that experience to avoid taking Germany to task last year over a minimum wage in the postal sector of €9.80 per hour. His formal complaint was triggered by the disgruntlement of the Dutch firm TNT which wanted to avail of the liberalisation of Europe’s mail services – something McCreevy has been championing – to encroach into the German market but felt the wages it would have to pay were excessive.

In the 1980s and ‘90s, McCreevy disparaged those who stood up for the disadvantaged by claiming they belonged to the “poverty industry”. Nowadays, he dismisses his critics as “pro-regulation junkies”. His put-downs can still be amusing. But the way he clings to ideological precepts that are as dangerous as they are outmoded has gone way beyond a joke.

David Cronin