The author of this article, Des Dalton, was a member of Republican Sinn Féin for over thirty years, serving as President from 2009-2018. He resigned from Republican Sinn Féin in March 2021 following an interview he gave to the University of Liverpool’s Institute of Irish Studies Civic Space in which he stated that the ongoing armed actions of republican groups such as the CIRA and New IRA could not be justified in present circumstances and were counterproductive. He holds a BA Hon in English and History from Carlow College.

The 1962 IRA Ceasefire: Lessons for Today. By Des Dalton.

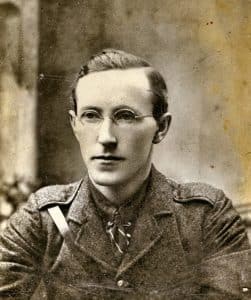

Sixty years ago, on February 26, 1962, the IRA announced the end of ‘Operation Harvest’, or as it has become known in popular parlance the ‘Border Campaign’.’ The statement, penned by the Chief of Staff of the IRA, Ruairí Ó Brádaigh, set out the reasons for ending the campaign. The thinking and conditions which informed the IRA leadership’s decision to end its campaign are not merely of historical interest but are relevant to Ireland of 2022.

Today there are a small section of traditional republicans, namely Republican Sinn Féin and Saoradh, who conflate the continuance of sporadic armed actions, however ineffectual and counterproductive, with keeping faith with traditional republican goals and ideals. They base much of their ideology on a reading of republican history that is deeply flawed.

Such an attitude and lack of historical understanding contrasts sharply with the IRA leadership of sixty years ago, who in announcing the end of their military campaign, did not signal any political retreat or compromise on the IRA’s core republican goals of securing a British withdrawal and the end of partition. For them the demarcation lines between the practical considerations of the means, and the principles and ideology of the end, were crystal clear. They were secure in their republican beliefs based on a sound historical understanding of the physical force republican tradition and their place in it.

The attitude of the IRA leadership in 1962 to the continuance of an armed campaign in unfavourable conditions was not unique. Similar discussions and analysis were grappled with and acted upon by IRA leaders such as Tom Barry, Frank Aiken and Liam Pilkington in 1923. It can be argued that in 1972 and 1975 Republican leaders such as Dáithí Ó Conaill and Billy McKee also proved capable of separating the means from the end in calling military cessations. In each case, adherence to core republican demands was reaffirmed while practical decisions on the efficacy of continuing an armed campaign were made coldly and logically.

The IRA launched its military campaign, which it labelled ‘Operation Harvest’ at midnight on the night of December 11/12, 1956, with a series of attacks across the Six Counties. From Torr Head in the far north of Antrim to Derry City, Magherafelt, Co Derry, Enniskillen, and other points around Lough Erne, Armagh attacks were carried out on a variety of targets from electricity powers stations, a courthouse, custom and B Special Huts, bridges and the British Army’s Gough barracks in Armagh, with varying degrees of effectiveness and success. Nevertheless, as J Bowyer Bell points out: “Ineffectual or not, the scale of the attacks, the presence of Cork men at Torr Head, and the possibility of further action had a sobering effect on the authorities at Belfast”.

By the end of 1961, despite a slight increase in attacks, mainly cratering of bridges, the cutting of the Dublin-Belfast rail line and the levelling of custom posts, it was increasingly evident the campaign was faltering, as Bowyer Bell noted “…the final spurt had still not reached a level beyond nuisance value”. All the measures of a functioning and effective republican movement were showing in the negative. The Garda Special Branch estimated IRA membership at 1,000, which according to Matt Treacy was “smaller than at any time since 1957.” Sinn Féin had a membership of approximately 5,000 members, with 336 cumainn. The movement’s paper the United Irishman, was printing 60,000 copies per month, half of the monthly print run in 1957. The number of active IRA volunteers had declined to about 50. The number of IRA operations had declined from a high of 341 in 1957 to 27 in 1959.In the October southern Irish general election Sinn Féin lost the four TDs it had seen elected in 1957, polling only 3% of the total poll, which had a profound effect on the morale of the remaining volunteers in the field.

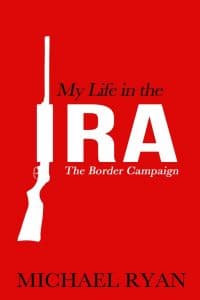

The introduction of Military Courts in November 1961, by the then Justice Minister, Charles J Haughey, is often perceived as the final nail in the coffin. In and of itself the introduction of increased draconian measures would not end the IRA’s campaign, but they certainly added significantly to an already growing list of problems. Then IRA Director of Operations, Mick Ryan, in his memoir, My Life in the IRA, says that even before the Military Courts were set up, the Army Council had decided to end the campaign “with minimum loss of prestige, men and ammunition”.

By the end of the year, Ó Brádaigh, his Adjutant General, Martin Shannon and Mick Ryan were the only members of the IRA’s GHQ still at large. When they met at the end of December their situation was bleak. According to Ryan “Police activity was intense, our billets had almost dried up, and the few that were still open to us were under regular surveillance. Free State intelligence had an almost complete breakdown of our structure or what was left of it.” Ryan estimated that by this point the arsenal of accessible and serviceable weapons numbered about twenty, with little or no transport or finance available. Ruairí Ó Brádaigh’s biographer, Robert W White states that it was Ó Brádaigh’s assessment at this point that “without a major operation the IRA would continue to decline, support would fragment into pockets, the organisation would have no real military capacity, and it would take years to recover, assuming that recovery was possible”. It is an assessment that could be applied, perhaps even more accurately, to the various armed republican groups still active in 2022, the Continuity and New IRAs, who are in a considerably weaker position than even that occupied by the IRA in 1962.

Mick Ryan records that such were the conditions under which they were endvouring to operate that even calling a meeting of the Army Council was a challenge. Following an abortive attempt in December, a meeting was eventually held in the west of Ireland on January 18, 1962. Present were Ruairí Ó Brádaigh, Seamus Costello, Denis McInerney, Paddy Fox, Redmond O’Sullivan, Tom Mitchell and Mick Ryan. The IRA’s Adjutant General, Martin Shannon was also in attendance. Just as starting the campaign had required a rigorous and considered examination of the objective conditions both on the ground and within the movement itself, so too did the decision to end the campaign. A decision was not made at the January meeting; Ryan states that it was believed that such a decision needed to be made by the twelve-member Army Executive. A second meeting of the Army Council was set for February 3. The Army Executive unanimously agreed to end the campaign and this decision was ratified by the Army Council. According to Tom Mitchell nobody spoke in favour of continuing the campaign and there was no vote. Afterwards, in the farmyard of the house where the meeting was held Mitchell spoke to Mick Ryan about the need for “another long process of reorganisation.” The prevailing attitude among leading republicans such as Ruairí Ó Brádaigh and Seán MacStiofáin was the Republican Movement was entering a period of reflection and reorganisation before moving on to the next phase of the struggle. In their view the IRA was far from dead.

On February 5, an order was issued to all IRA units instructing them to place their arms in secure dumps and to withdraw from the border. The date and issuing of a final ceasefire statement was delegated to GHQ. As Mick Ryan pointed out, this in effect meant Ó Brádaigh as “the only one capable of framing and writing such an important document.” Once drafted the statement was passed around the other members of the Army Council for their careful perusal. The final statement thus, was “a collaborative effort,” according to Robert White, representing the position of the Army Council and Army Executive.

The statement was released by the Irish Republican Publicity Bureau on the evening of February 26, 1962, under the nom de guerre “J. McGarrity”, used by the IRA since its last major reorganisation in 1948/49, a nod to the memory of the legendary Clan na Gael leader Joe McGarrity. The statement was addressed “To the People of Ireland.” The most common criticism of the statement was that it laid the blame for the failure of the campaign at the door of the Irish people themselves. This was based on the claim in the statement that “Foremost among the factors motivating this course of action has been the attitude of the general public whose minds have been deliberately distracted from the supreme issue facing the Irish people – the unity and freedom of Ireland.” Ó Brádaigh denied that this was the case, contending that this was a reference to the campaign by the Sean Lemass led Dublin Government to join the then European Common Market, with people being told that membership of the Common Market would make the border disappear. A sentence later in the same paragraph would seem to support Ó Brádaigh’s contention: “This calculated emphasis on secondary issues by those whose political future is bound up in the status quo and who control all the mass media of propaganda is now leading the people of the 26 Counties towards possible commitment in future wars.” A statement by the Sinn Féin Publicity Committee, carried in the United Irishman in the April, 1962 edition echoes this view: “To state that under Common Market conditions, the border will become ‘even more than ever now a patent and obvious absurdity’ is a deliberate and calculated attempt to mislead people into the completely erroneous belief that with Ireland’s membership of the Community the border and partition rule in Ireland will come to an end.”

The statement condemned the “collaborationist role of successive 26-County Governments – acting under pressure from the British – from December 1956 has contributed material aid and comfort to the enemy.” The use of internment and other coercive actions such as house raids were also referenced. The statement also accused “professional politicians of the 26 County state” of misrepresenting the methods, aims and objectives of the IRA both at home and on the international stage.

The statement reiterated the IRA policy, in place since 1951, of “not taking aggressive military action within the 26-County area remains unaltered.” It ended on a note of defiance and with an eye to the future: “The Irish Republican Army renews its pledge of eternal hostility to the British Forces of Occupation in Ireland. It calls on the Irish people for increased support and looks forward with confidence – in co-operation with the other branches of the Republican Movement – to a period of consolidation, expansion and preparation for the final and victorious phase of the struggle for the full freedom of Ireland.”

Over the course of a five-year campaign the IRA had managed to carry out a significant guerrilla campaign, engaging in 600 operations. The New York Times estimated that the campaign had incurred $14 million in damages to the infrastructure of the Northern Irish state. It was also estimated that the Dublin and Belfast governments had spent $28 million in maintaining their respective police and military forces. Over the course of the campaign ten republicans had been killed, eight members of the IRA, one member of Sinn Féin, James Crossan and a republican sympathiser, Michael Watters. Six members of the RUC were killed, and 32 members of the British military and police wounded. At the end of the campaign there were 75 Republican prisoners, 43 in Crumlin Road Belfast, 29 in Mountjoy prison, Dublin, and three in prions in England, two of whom were serving life sentences. The Dublin Government released all republican prisoners less than two months after the ceasefire on Good Friday. The Stormont Government did not release their republican prisoners until September 1963. The life sentence prisoners in England were released in July 1962.

Wider reaction to the statement was mixed, the Dublin Government’s Minister for Justice, Charles J. Haughey welcomed the statement while also reaffirming that his government was not “prepared to tolerate the existence of unofficial organisations,” saying that they will “continue to use all the powers at their command to see than an end is put to all activities of this kind.” He expressed what he said were “the hopes of many in urging those concerned to turn their attention to constructive purpose. The nation can do with the services of all her citizens.” The Stormont Government were much more cautious. Speaking in Stormont, the Home Affairs Minister, Brian Faulkner, while welcoming the end of the IRA campaign noted “the terms of the statement however with their reference to ‘a period of consolidation, expansion and preparation of the final victorious phase of the struggle’ make my welcome subject to reservations.” The Irish Times, urged the Dublin Government to show caution in the release of republican prisoners “to ensure the reconciliation of its present prisoners with their new condition and to reduce the tension between Dublin and Belfast.”

Ironically the strongly unionist Belfast News Letter was more accurate than most in deciphering the true meaning of the statement, declaring that it represented “not an abandonment of the campaign but a strategic retreat, with the intention of fighting another day.”

This was the message that would be reiterated by leading republicans in the subsequent weeks and months. Tom Mitchell, speaking at the grave of one of the fallen heroes of the campaign, Fergal O’Hanlon, in Lathlurcan Cemetery in Monaghan on Easter Sunday told those assembled that: “Active resistance may have ceased for a while but only in order to strengthen the Movement. This is a time of preparation and not a time for rest.” While the Easter Statement from the leadership of the Republican Movement reassured the republican faithful that: “The Resistance Movement is intact and has already embarked on the work to be done in the new era.” These sentiments would be reiterated by the President of Sinn Féin, Tomás MacGiolla in his oration at the premier event in the republican calendar, the Wolfe Tone commemoration at Bodenstown, Co Kildare in June that year.

This was not the first time that a republican leadership had wrestled with a similar dilemma. Following the death of IRA Chief of Staff, Liam Lynch in April 1923, the Army Executive, Army Council and Republican Government were faced with demoralisation and the steady erosion of people and materials as the Free State Government asserted its supremacy. Led by the new Chief of Staff, Frank Aiken, legendary IRA leaders such as Tom Barry and Liam Pilkington came to the conclusion that a continuance of the military campaign against the Free Sate would lead to the complete disintegration of the Republican forces in the field and set back any opportunity to reorganise by years. On May 24, 1923, Frank Aiken issued an order to “Dump Arms” declaring “the arms with which we have fought the enemies of our country are to be dumped. The foreign and domestic enemies of the Republic have for the moment prevailed.” Two days later, the President of the now underground Republican Government, Éamon de Valera issued a proclamation addressed to “Soldiers of Liberty! Legion of the rearguard,” which stated that “Further sacrifices on your part would now be in vain, and continuance of the struggle in arms unwise in the national interest. Military victory must be allowed to rest for the moment with those who have destroyed the Republic.” The historian Michael Hopkinson succinctly summed up the position of republicans at the end of the civil war: “No ground had been conceded on the constitutional and political issues which had caused the conflict. The Civil War, therefore, ended without any negotiated peace, and in many respects the Twenty-Six Counties remained on a war footing.” Hopkinson’s assessment of the IRA’s position in 1923 could as easily be applied to the IRA in 1962.

Sixty years on from the 1962 Ceasefire it is timely to reflect on what if any relevance it has for the Ireland of today. I believe that it carries a relevance for those seeking an understanding of the ideology of traditional Irish Republicanism. Maintaining an armed campaign or carrying out sporadic armed actions without any end clearly defined goal or overall strategic thinking or leadership is not a principle but on the contrary serves only to damage the long-term attainment of core republican objectives. In an interview for Marisa McGlinchey’s recent article ‘The unfinished revolution of “dissident” Irish republicans: divergent views in a fragmented base’, former H Block Hunger Striker Tommy McKearney argues that the use of force is simply a ” political option […] but if republicanism is equated just simply with the use of force, then it makes it a fetish”.

The practical question around the utility of an armed campaign was met head on by previous republican leaders, none of whom could never be accused of having ‘sold out’ on traditional goals such as Tom Barry, Liam Pilkington, Mary MacSwiney, Ruairí Ó Brádaigh, Denis McInerney, Paddy Fox etc. These were men and women who would remain faithful to the ideal of a 32-County Irish Republic throughout the course of their lives. But as republican leaders they also recognised that they had a solemn responsibility for the lives and liberties of, not only those who had placed their trust in them as leaders, but for the Irish people as a whole.

When the British Government indicated in December 1974 that it wished to “establish structures for a British withdrawal from Ireland”, leaders such as Ruairí Ó Brádaigh and Billy McKee knew what was expected of them. According to Ó Brádaigh “It was a feeling of responsibility that people had to make the most of this. If there was a way out of this centuries old conflict. If there was a way of getting British withdrawal in whatever manner.” No backward steps were taken on fundamental republican principles, instead each of those leaderships displayed an ability to rationally analyse and access the situation and act accordingly.

Drifting from one haphazard armed action to another, while people go to jail for long periods of time and lives are endangered or lost, displays neither leadership nor principle. As Marisa McGlinchey pointed out in an article in 2021, even making these points, or posing these questions, often results in accusations of sell-out. The armed republican groups of today would do well to reflect on the lessons to be drawn from 1962.

Sources:

Bowyer Bell, The Secret Army: The IRA,

Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green: The Irish Civil War,

Michael Ryan, My Life in the IRA: The Border Campaign,

Matt Treacy, The IRA, 1956-69: Rethinking the Republic,

Robert W. White, Ruairí Ó Brádaigh: The Life and Politics of an Irish Revolutionary,

Carlton Younger, Ireland’s Civil War,

Marisa McGlinchey (2021) The unfinished revolution of ‘dissident’ Irish republicans: divergent views in a fragmented base, Small Wars & Insurgencies, 32:4-5, 714-746, DOI: 10.1080/09592318.2021.1930368

The United Irishman, May 1962,

Belfast Telegraph, February 27, 1962,

Belfast News Letter, February 27, 1962,

The Irish Times, February 27, 1962

![]()