Boiling water contaminated with THMs does not make it safe; it compounds the danger. Ireland is now in clear breach of EU law and permitting a growing risk to public health.

By Tony Lowes

Uisce Éireann is failing to warn the public about a dual risk: the health threat posed when consumers are told to boil water that is already contaminated with dangerous levels of Trihalomethanes (THMs). That’s the stark message from Friends of the Irish Environment (FIE), which has written to Uisce Éireann, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Minister for Climate, Energy and the Environment, and the Health Service Executive.

Boil water notices are being issued in areas where THM levels exceed safe limits and consumers are being advised to boil water without being told that this increases exposure to harmful chemicals

Our central concern is this: boil water notices are being issued in areas where THM levels exceed safe limits, and consumers are being advised to bring water to a “vigorous, rolling boil” without being told that this process increases exposure to harmful chemicals. Boiling water contaminated with THMs does not make it safe; it compounds the danger. Ireland is now in clear breach of EU law and a permitting a growing risk to public health.

Boiling water contaminated with THMs compounds the danger

According to the press release issued by FIE on 10 June 2025, “Ireland has failed in its obligation to provide clean and wholesome water as required by EU law and continues to supply a large number of households with water polluted with toxic chemicals.” This failure is backed up by data from the EPA, which shows that “the number of people served by ‘at risk’ public water supplies has increased again in 2023 to 561,000, up from 481,000. The increase is primarily due to detections of persistent Trihalomethanes [THM] and cryptosporidium.” One in twenty supplies failed to meet the THM standard in 2023 [1].

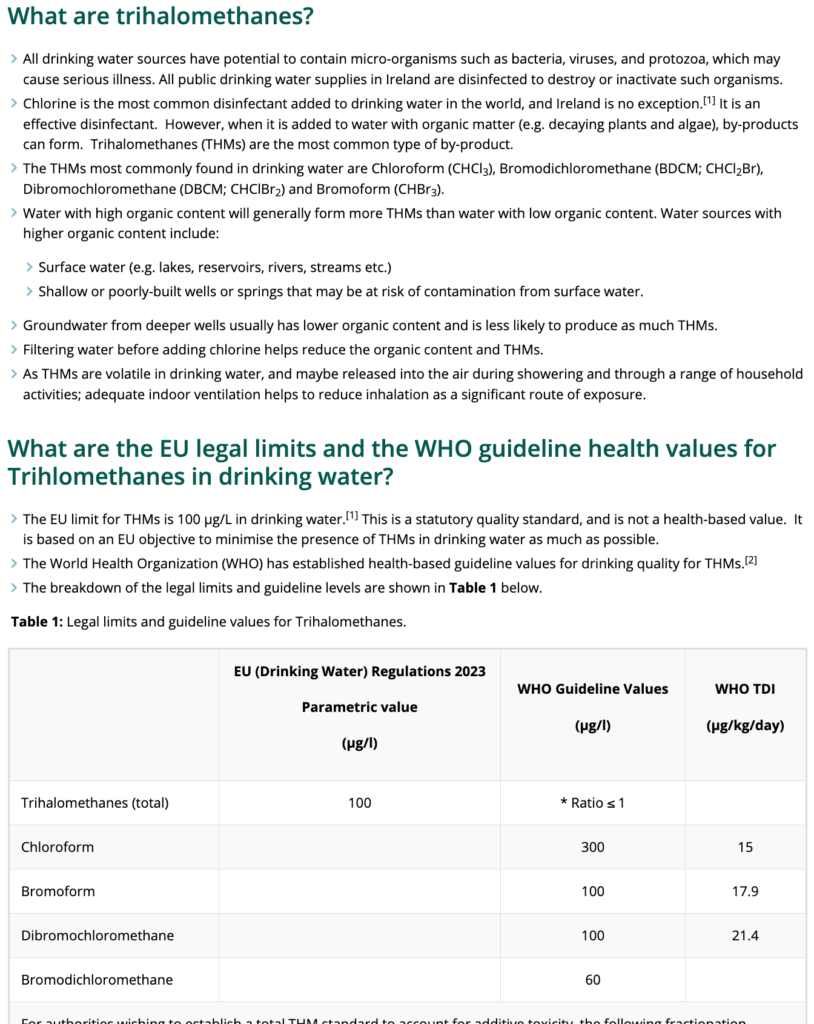

THMs are a group of more than 60 chemical by-products, including chloroform, created when chlorine added as a disinfectant reacts with organic materials in the water, such as peaty soil. Long-term exposure to elevated levels of THMs has been associated with increased risk of cancer, particularly bladder cancer, and adverse reproductive outcomes such as low birth weight and small-for-gestational-age infants [2, 3]. These risks are amplified in everyday domestic settings through activities such as showering and bathing, which increase both inhalation and dermal exposure to these chemicals.

While the HSE maintains that chlorine cannot be reduced without risking bacterial contamination, FIE argues that “the issue can, in fact, be addressed by simple charcoal filters” [4]. Despite this, no systematic provision or recommendation for such filters has been implemented in affected areas.

Issuing boil water notices for contaminated supplies without informing the public of these inhalation and dermal risks creates what FIE calls a “dual risk.” Tony Lowes explained that “boiling water with THM poses a significant long-term health hazard by releasing the toxic chemicals into the atmosphere with impacts including an increased risk of bladder cancer.”

Scientific research confirms these dangers. Studies show that blood concentrations of THMs can rise five- to fifteen-fold during showering, and bathing and hand dishwashing also significantly increase THM exposure. These results underscore that boiling contaminated water in enclosed environments can, paradoxically, elevate the health risk it is supposed to reduce [2].

Despite these known dangers, Uisce Éireann continues to advise a “vigorous, rolling boil” of water without qualification. The absence of transparent warnings on this compounding risk is a major failure in public health messaging and may expose the State to liability.

The problem is not hypothetical. The FIE press release details multiple affected water supplies. A brief boil water notice in Limerick affected 113,764 consumers. Persistent notices continue in:

- Whitegate (9,011 consumers)

- Galtee, Tipperary (11,379)

- Foynes/Shannon Estuary, Limerick (6,986)

- Barrow Supply, Kildare (80,592)

- Glashaboy, Cork (23,087)

According to the EPA’s Q4 2024 Drinking Water Remedial Action List, 11 of the supplies exceeding permitted THM levels still have no plans for action and are listed as “to be submitted by Uisce Éireann” [5].

FIE notes that this issue was first highlighted in 2016, when the group lodged a complaint with the EU regarding Carraroe, County Galway [7]. The resulting 2024 judgment from the European Court of Justice confirmed that Ireland had breached the Drinking Water Directive. FIE argues that the situation has worsened since that judgment.

That judgment, based on years of inaction, detailed how Ireland had failed to adequately monitor, report on, and address chemical contamination in its public water systems. It emphasised the principle of preventative action in EU environmental law, and highlighted how vulnerable communities were being left with unsafe water for years. The Court found that even when remedial action was planned, delays in implementation rendered Ireland non-compliant with its obligations.

In some cases, families living in affected areas report relying on bottled water for drinking and cooking for years, at personal expense. In rural areas especially, people on small group water schemes face barriers in accessing filters or alternative supplies. There is frustration, too, at the lack of public engagement. Citizens are rarely consulted on remedial plans, and communication about risks often comes only after media attention or pressure from environmental groups.

Comparatively, Ireland’s handling of THM contamination contrasts sharply with the approach taken in other EU member states. In Denmark, for example, water authorities routinely publish detailed chemical profiles of local water, including all THM levels, in public databases updated quarterly. In France, where THM issues were discovered in Brittany, local health authorities launched immediate door-to-door awareness campaigns and offered subsidies for household filters. In both cases, transparency and action reduced risk.

By contrast, in Ireland, even basic transparency is lacking. Information is often buried in technical documents or behind freedom of information requests. The EPA’s own remedial action list, while important, gives only high-level overviews with limited narrative. No map of affected zones has been made public, and boil water notices continue to be issued without reference to the chemical profile of the water involved.

Moreover, the State’s failure to act is all the more striking given the modest cost of available solutions. Activated carbon filtration at household or supply level is affordable and effective. So too are investments in source protection and natural filtration restoration, as recommended by multiple EPA reports. Yet for many years, political energy has focused on structural issues like water charging, while operational public health risks have been under-addressed.

The human cost is not abstract. Chronic exposure to THMs has been linked not only to bladder cancer but also to spontaneous abortions and other reproductive issues. These findings, detailed in EU-funded cohort studies, are particularly relevant for households with young children or people planning families. And still, official guidance to boil water remains unchanged.

FIE has written to the Chairman of Uisce Éireann, the Minister for the Environment, the HSE, and the EPA, warning that the State risks serious legal and financial consequences if it does not act swiftly and transparently. The group has called for the following steps:

- Immediate public health warnings in all boil water notices where THM levels are above the safe limit.

- Provision of activated carbon filters to affected households as a temporary but effective solution.

- Publication and implementation of detailed remediation plans for all non-compliant water supplies.

- Coordination among regulatory agencies, particularly the EPA and HSE, to ensure consistent guidance and accountability.

This crisis is not isolated. It is part of a pattern of failure in Ireland’s water infrastructure and governance. In 2015, Village Magazine published an article titled “Back to School” that detailed lead contamination in school drinking water. That story exposed bureaucratic delays, confusing chains of responsibility, and a lack of urgency—failures echoed in today’s THM crisis.

The difference in 2025 is the scale. The current issue affects not just children in specific schools, but hundreds of thousands of citizens in their homes. And it does not concern just one contaminant, but multiple routes of exposure: ingestion, inhalation, and skin contact.

We are not asking for miracles. The technologies exist. The data is public. The legal obligations are clear. What is missing is the political will to treat the issue with the seriousness it deserves. Even in small community water systems across Europe and North America, simple interventions—like public filters, warning signage, and water source upgrades—are routinely deployed. Why not here?

Unless the government takes immediate action to end the dangerous practice of issuing boil water notices for THM-contaminated supplies without appropriate warnings, Ireland will continue to violate EU law and jeopardise public health. The consequences will be legal, financial, and moral.

It is long past time to stop asking consumers to choose between bacterial contamination and chemical poisoning. Safe, clean drinking water is a right, not a privilege. The State must act like it.

Tony Lowes is a Director of Friends of the Irish Environment

References: [1] Environmental Protection Agency (2024). https://www.epa.ie/news-releases/news-releases-2024/while-water-quality-is-very-high-the-resilience-of-drinking-water-supplies-must-improve-and-will-require-sustained-investment-into-the-future-says-epa.php [2] Nuckols, J.R. et al. (2005). Environmental Health Perspectives. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.7141 [3] Grazuleviciene, R. et al. (2011). Environmental Health, 10, p.32. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069X-10-32 [4] HSE (2024). https://www.hse.ie/eng/health/hl/water/drinkingwater/trihalomethanes/ [5] EPA Drinking Water Remedial Action List Q4 of 2024. https://www.epa.ie/publications/compliance–enforcement/drinking-water/annual-drinking-water-reports/epa-drinking-water-remedial-action-list-q4-of-2024.php [6] FIE (2024). https://friendsoftheirishenvironment.org/news-archive/ireland-convicted-in-eu-court-over-unsafe-drinking-water-tainted-by-chemical-linked-to-cancer [7] FIE (2016). https://www.friendsoftheirishenvironment.org/press-releases/galway-boil-water-notice-creates-further-health-risks