My brother told me about a stag weekend he went to recently. The bus that was taking them to Galway hosted an online game where they bet on virtual horses. On arrival, the fellas announced that they had organised a poker night for the husband-to-be. The next day they went to the races. ‘Wow’, you might think, ‘gambling is a popular entertainment for young men today’. But how did gambling go from a furtive preoccupation of the older man to an apparently cheeky, funny, harmless entertainment for the young man?

Gambling has a long and varied history, but it was not until the early 1900s that it became a mass activity, with the development of licensed high-street betting shops. These then expanded from individual family bookmakers into some of the commercial high-street chains of the modern betting industry. Telephone betting began in the early 1990s and in 2001 the Irish bookmaker Paddy Power was the first to move into Internet betting, before becoming first mover on the Apple App Store in 2010. In the past decade, neurological marketing research, consumer profiling, single-click betting, geo-tracking mobile technology, virtual reality, and real-time ‘in-play betting’ have led to a seamless, intensively immersive and pervasive market.

Through this technology-driven marketing approach, gambling companies have achieved three objectives. First, they have fundamentally changed the public image of gambling by a marketing process known as normalisation. Second, they have diversified the range of ways in which people can gamble, expanding access to gambling touchpoints, increasing the range of what can be gambled on, and reducing the obstacles to gambling – a process we call the gamblification of life. And finally, they have waged an undeclared public relations war to ensure that successive governments don’t interfere with the soft-touch regulatory environment in which they thrive.

What has it led to? An estimated 40,000 people have a gambling addiction in the Republic of Ireland. Recently, the Economist magazine calculated the per capita gambling losses by country: Ireland ranks third in the world, and first when it comes to online losses (graph below). 80% of Irish people who bet on sports events have at least one online account. Ireland has grown leading international and internationalizing gambling brands such as Paddy Power, Boylesports and most recently Quinnbet, Sean Quinn’s online gambling company launched in August 2017.

In an experiment broadcast by BBC ‘Panorama’ last year, MRI imaging revealed that an addict’s brain exhibits the same neurological state whether it is anticipating a spinning roulette wheel, placing a bet, or in fact winning. This suggests that gamblers are addicted not as much to the end goal of winning as to the thrill of being involved in a betting experience.

This neurological evidence for gambling allows two things to happen that are advantageous to the industry: it gives better insight into how reward centres in the brain are stimulated, and it offers clues as to how to naturalise addiction and thus limit discussion of the role that marketing plays in creating gamblers. In our research on the gambling market in Ireland, it was striking that marketing managers in the industry would repeatedly talk about gambling addiction as a neurological dysfunction, specifically in the brain’s mesolimbic reward system, that about 10% of the population are predisposed to. Portraying the other 90% of gamblers as ‘problem-free’ is therefore a useful tactic in denying that gambling may be a condition that is caused, and even fostered, by the industry.

The new vulnerability

So who is the ‘problem gambler’? From a psychological perspective, there are two recognisable characteristics. First, the gambler has diminished control over the time or the money they spend, and second, their gambling results in negative consequences for them and/or for someone close to them. Contrary to our traditional view of gambling as older, working-class men in bookmakers, the majority of problem gamblers are young men, aged 18-24. Surprisingly perhaps, a higher level of academic education correlates with an increased risk of problem gambling. And perhaps unsurprisingly, 1 in 5 problem gamblers attempt suicide.

And, contrary to policy rhetoric that seeks to solve problems by pointing out that people merely ‘need to know the dangers’, evidence points to a very high level of addiction within the industry – proof that those with the most knowledge of the market are not immune to it. To compound matters, problem gamblers within the male demographic are least likely to admit they have a problem, and their behaviour is often not recognised by themselves or by others as problematic, but rather as normal young male behaviour. This cocktail of factors makes it especially difficult to reveal the scale of the problem that this market creates.

Funning Risk

Gambling brands position gambling as a harmless activity. This normalises its pervasiveness, frequency and intensity. Often, animations are used to appeal to young consumers, the tone is jocular, and there is never a reference to losing. The injunction to have fun is an especially important positioning tool that resonates with young men who are seen as more acceptable when they are jokey, laddish, and in good humour – an injunction which increasingly spills into other domains – we must be fun at work, we must be a fun dad, and so on. Alongside the fun archetype, the second most used archetype is that of the hipster, with major gambling brands encouraging the perception that gambling is a James Bondesque talent or skill which can be learned and developed, rather than a game of chance where the odds are stacked against you.

Of course advertising is a way of enticing existing gamblers to gamble more, but it’s also a mechanism to educate the next generation of gamblers in brand awareness and preference: gamblers develop problem behaviour most often during adolescence, when they are most exposed to televised sport. Advertising frequently demonstrates not only the fun of betting, but how to bet, as in the Bet365 advertisement shown here. Sponsorship is another mechanism of normalisation, particularly in sport. For example, in the 2015/16 season, five English Premier League Football Clubs were in partnerships with Betfair alone. In fact, 9 of the 20 clubs in the English Premier League display gambling sponsors on their jerseys. Simple parts of the football game’s ceremony like players shaking hands turn into split screens, to allow the gambling sponsor to dominate the message. There is a different pattern of infiltration in Irish soccer, where the FAI has blundered in the last two years by entering business arrangements with Ladbrokes and Trackchamp.

Celebrity endorsement is another powerful mechanism that is repeatedly proven to be an effective way of encouraging gambling. While the Advertising Standards Authority for Ireland website claims that marketing should not “contain endorsements by recognisable figures who would be regarded as heroes or heroines of the young”, instantly recognisable sports stars such as Liverpool manager Jürgen Klopp serve as ambassadors for gambling brands during live sporting events which children regularly watch.

While advertising, in the forms of sponsorship, celebrity endorsement, ‘fun’ billboards and PR stunts all lead to the gamblification of life, there are much more subtle ways that the betting mentality enters the mainstream. Match commentary and punditry are among the most important ways that gambling is normalised. To take only one of countless examples: in RTÉ’s coverage of the Champions League football on 15 February 2017, the pundit Eamon Dunphy commented, “The key was Koscielny, he is a leader, he is a good player and when Gabriel came on for him, I rushed to the phone and had a bet”.

Beyond Publicity

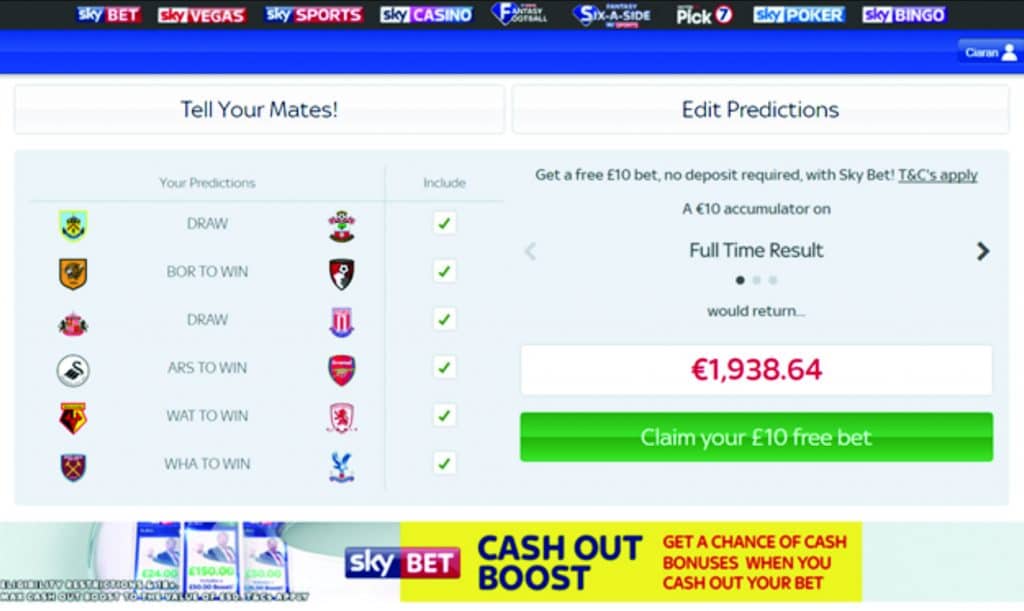

The gambling industry has proved highly innovative in its approach to interactive media. One example is ‘slippery slope’ technology, where companies create what are seemingly attractive deals and then proceed to complicate those deals to entrap consumers. Take for example Sky Sports Television which runs a weekly free predictions competition, known as ‘Super 6’, with a prize of £250,000 if you predict 6 correct scores. Upon predicting these scores the player receives an offer to place money on these results through a Sky Bet account. In the screen above, we see how the free prediction is then framed as a successful bet, and a free £10 bet is offered, blurring the line between a prediction game and an online gamble. These types of slippery slope technologies are a crucial mechanism to induce non-gamblers into gambling, and are very effective.

If a gambling addiction is a disease, then online betting gives it three things it needs to thrive: anonymity, accessibility and 24-hour availability. Over the past decade, the crucial driver of the 18 to 24-year-old male market has been mobile technology. In fact, online betting has surpassed all other forms in participation rates. But it is the rise of the new innovation of ‘in-play betting’ that is a key factor in addictive betting and higher expected losses.

In contrast to traditional forms of gambling, where bets happen before a game or match takes place, in-play betting happens only after a match has started. Live odds-updates are flashed across the screen in real time, a technique that is raking in new participants to make impulse bets with easy accessibility to the online or app platform. Without allowing sufficient time to think and reflect, these bets result in more impulsive decisions, and many of the in-play bets tend to be larger with higher risk. According to our research, up to five different sports-betting companies take part in in-play advertising during 90-minute football matches.

Each gambling brand employs an army of social media marketers to produce an immersive, interactive experience. It is, after all, a central tenet of marketing theory to increase the efficiency between systems of production and systems of consumption. Online betting is easily accessible and can be done in isolation rather than at licensed gambling premises or at live events such as horse races. 93% of adolescents have directly experienced pop-up promotions from gambling organisations, subsequently seeing gambling promotions, irrespective of their age. Problem gamblers have been shown to find it increasingly difficult to avoid a relapse with this ease of access.

Addicts of drugs or alcohol do not have the same instant supply of harmful substances promoted on their smartphone in their pocket. Social media is now a vital part of the life of adolescents and this form of digital media is barely regulated, if at all. By 2015, 1.8 million people were using Facebook in Ireland daily, while 70% of Irish companies have a Facebook account. Consumers who engage with gambling companies on their social media, for any reason, are constantly offered free bets.

Public relations war and the privatisation of responsibility

There is growing interest in the industry in voicerecognition technology. An industry manager in a leading Irish gambling company we recently interviewed believes this could transform the betting experience as much as the introduction of the gambling app. While in Ireland, we have started to see the emergence of sports stars such as Davy Glennon speaking out about their personal stories of gambling addiction, and this is welcome, none condemn the industry and its marketing strategies.

Up to now, all social marketing campaigns promoting responsible gambling have tended to put the responsibility on the consumer, to gamble responsibly. This is because most anti-gambling charities are funded by the gambling industry, thus insuring that responsibility for addiction is kept at the level of personal responsibility. Online betting operators, such as Paddy Power, not only direct ‘problem’ gamblers to these agencies, but also charge a ‘Dormant Account Fee’ to customers who do not place bets over an extended period of time, as shown below, encouraging customers to bet regularly.

Policy Interventions

The 2015 Betting Act did little to improve things. Its only action on online gambling companies was an amendment requiring them to get a licence. Meanwhile the Gambling Control Bill of 2013, a more potentially effective piece of legislation, is gathering dust while tens of thousands of young people go bankrupt, devastate their families and on occasion attempt suicide because of gambling. The money spent on promoting gambling dwarfs government and NGO spending on mechanisms to create social awareness of problem gambling. Vast levels of exposure through televised sports have resulted in normalisation and acceptance of gambling, giving the industry credibility and endowing the activity with an air of harmlessness. Responding to gambling problems by simply banning television advertising might not be the answer, for two reasons. First, simply raising awareness of the problem, of any problem, that has been caused by marketing can create a boomerang effect: research has shown, for example, that young males find anti-gambling messages patronising and authoritarian. Second, as the gambling industry moves to dynamic promotions, in particular live in-play sports betting, regulation of messages becomes more difficult and is in danger of lagging behind industry innovation.

In light of the above, we advocate:

1. Creating an interactive gambling amendment bill, similar to the recent Bill in Australia, that bans in-play betting.

2. Obliging gambling companies to share their marketing research with non-partisan gambling charities and research agencies so they may better understand the psychology of online gamblers.

3. Banning gambling advertising during children’s television hours, including during live sporting events.

Norah Campbell is Assistant Professor of Marketing in Trinity Business School, Trinity College Dublin.

Ciaran Williams is a graduate of Trinity Business School, with research interests in business, marketing and technology.