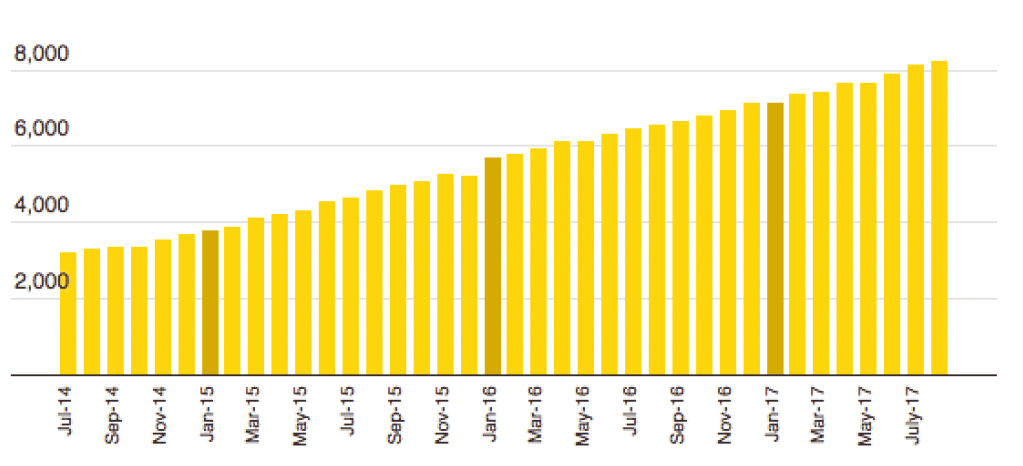

The latest figures from the Department of Housing show there are now 3,048 children (from 1,442 families) homeless in Ireland. That is a 282% increase on the number of children homeless in August 2014 (when there were 385 families and 796 children homeless). This level of increase in homelessness shows the complete failure of policies to address the crisis. It shames this government, previous governments and the entire nation that we are destroying the dignity of our most vulnerable citizens – our children – by leaving them without their most basic of needs, and fundamental human right – a secure home.

The research for our recently published report ‘Investing in the Right to a Home: Social Housing, HAPs and HUB S’, conducted in the context of a larger European Union Horizon2020-funded research project, Re-InVest, shows the reality of life in emergency homeless accommodation, including the new ‘Family Hubs’.

Using a human rights and capability framework we find these hotels and hubs restrict the capacity of the homeless families to live normal family lives and curtail functioning in their parenting, child development, education, employment and maintenance of family and social networks. Devastating impacts on family, adult and child well-being ensue.

Our research reveals that the structural causes of the crisis of family homelessness in Ireland are the shift away from the direct building of social housing by local authorities, and neoliberal policies that have marketised, privatised and financialised the delivery of both social and private housing.

These have transformed housing into a speculative commodity rather than a basic need and human right. Austerity dealt social housing a fatal blow – as the state went from building over 7000 local authority housing units in 1975 to just 65 in 2015. Delivery of social housing was shifted primarily to the private rental market in 2014 with the introduction of the Housing Assistance Payment – and then cemented in the government’s 2016 housing plan ‘Rebuilding Ireland’ – where private rental housing is to constitute 65% of planned new social housing.

In the short term, HAP is expected to provide 32,000 households with ‘social housing’ in 2017 and 2018. In contrast just 15% (21,300) of the 134,000 ‘new’ social housing units outlined in ‘Rebuilding Ireland’ will be new-builds by Local Authorities and Housing Associations.

From a cost perspective, direct-build social housing presents a far greater return on state investment than the private rental HAP approach. Our cost-benefit analysis (based on Mel Reynolds’ formula – see Village June 2017) shows that over a 30-year time-frame HAP will be €23.8bn more expensive than local authority provision. This €23.8bn could still fund the building of 132,495 permanent social housing units (at a cost of 180,000 per unit) over this period.

If the approach in ‘Rebuilding Ireland’ continues there could be in excess of 120,000 households in receipt of various state subsidies in the private rental sector by 2021, requiring state spending of approximately €1bn annually, most of which will be going to private landlords, including RE ITs and global investment funds. Providing these 120,000 social housing units through HAP will be €32.9bn more expensive than local authority provision over a thirty-year period.

We undertook a thorough analysis of ’Rebuilding Ireland’. The social housing aspect of the plan makes it clear that the government’s primary strategy for providing additional social housing is through the private rental sector, the HAP, with over 65% of social housing (87,000 units of the total 134,000) to come from the private rental sector over the 2016-2021 period.

In the short term, HAP is expected to provide 32,000 households with ‘social housing’ in 2017 and 2018. In contrast just 15% (21,300) of the 134,000 ‘new’ social housing units outlined in ‘Rebuilding Ireland’ will be new-builds by Local Authorities and Housing Associations.

Ireland has a long history of gendered forms of social violence inflicted on poor mothers and children who were made invisible, incarcerated and excluded from society. We caution that hubs may be a new form of institutionalisation of vulnerable women and children, and poor families.

We found that the headline social housing figures disguise the reality of an extremely low level of planned new build social housing and overdependence on the private market to provide social housing. Not only are such targets insufficient but they are also unlikely to be met because of the over reliance on the private market. In 2017, on the basis of Q1 construction figures of new 235 build social housing units it suggests the state will build around 1000 units in 2017 which is just a third of the ‘Rebuilding Ireland’ target.

The resulting low level of social housing indicates a lack of institutional and political will, as distinct from rhetoric. For example, in the four Dublin local authorities there are just 1000 units on-site and a further 1900 at various stages of procurement/planning. Over the coming the years that’s under 3000 new build units – not even enough to house all those who will become homeless and those currently in emergency accommodation. With waiting lists of 40,000 in the Greater Dublin Area it will be 40 years before the state houses those on the housing lists in greater Dublin area.

We argue that there is a real danger that family ‘hubs’ work as a form of ‘therapeutic incarceration’ both institutionalising and reducing the functioning capacity of families. Ireland has a long history of gendered forms of social violence inflicted on poor mothers and children who were made invisible, incarcerated and excluded from society. We caution that hubs may be a new form of institutionalisation of vulnerable women and children, and poor families (predominantly lone parent mothers; and working class, migrant and ethnic-minority women). Therefore, we recommend that families should not be left in hubs for longer than three months. They should be provided suitable social housing within that time and there should be a sunset clause for family hubs, to be closed by 2019.

We also highlight that at the core of the crisis is the absence of the right to housing for Irish citizens. The 2015 Constitutional Convention recommended that the right to housing should be enumerated in the constitution. A human rights approach to housing would lead to practical policy changes. For example, the state would provide access to adequate and secure housing for all citizens. There would be an adequate system for service users’ participation and consultation, and for redress and safe-guarding entitlements, but it would also provide an over-arching philosophical and value frame to guide housing policy to ensure that the right to housing is prioritised over other interests – such as property investors’ profits.

This housing crisis will continue for many years to come. Given the on-going mortgage arrears crisis, the private-rental crisis, and the lack of private supply, HAP, even with reconfiguration, is unlikely to provide a stable and secure home for these families.

It is our view that the homelessness crisis is not being given sufficient political priority and the wrong solutions are being put in place. Giving or lending money to developers through NAMA or otherwise is a nonsense that notably serves longstanding vested interests. We are destroying the lives and dignity of thousands of our most vulnerable citizens and children in particular.

Instead we consider the state must move away from failed private, market and speculative approaches to housing and implement an emergency housing plan based on four imperatives:

-

Put the right to housing as the guiding policy objective and hold a referendum to insert the right to housing in the Constitution

-

Change the Private Tenancies Act to provide tenant security from eviction

-

Increase state funding for housing to €2bn per annum to provide a state-led housebuilding programme of 30,000 social and affordable homes per annum – local authority construction of 10,000 houses; and various housing co-ops, a new housing agency, and associations building 20,000 affordable rental and purchase homes.

-

Redirect government-owned land for emergency social and affordable state-led house-building, rather than marketing and privatising it to developers in various Public-Private-Partner ships and ‘Lands Initiatives’.

The housing crisis, which is an emergency, and should be declared officially as such, has grown to affect a very large proportion of society and jeopardises our economic well-being. To avert the despair, it’s time for change.

Dr. Mary Murphy is a Senior Lecturer and Dr. Rory Hearne is a post doctoral researcher, at the Maynooth University Social Sciences Institute.