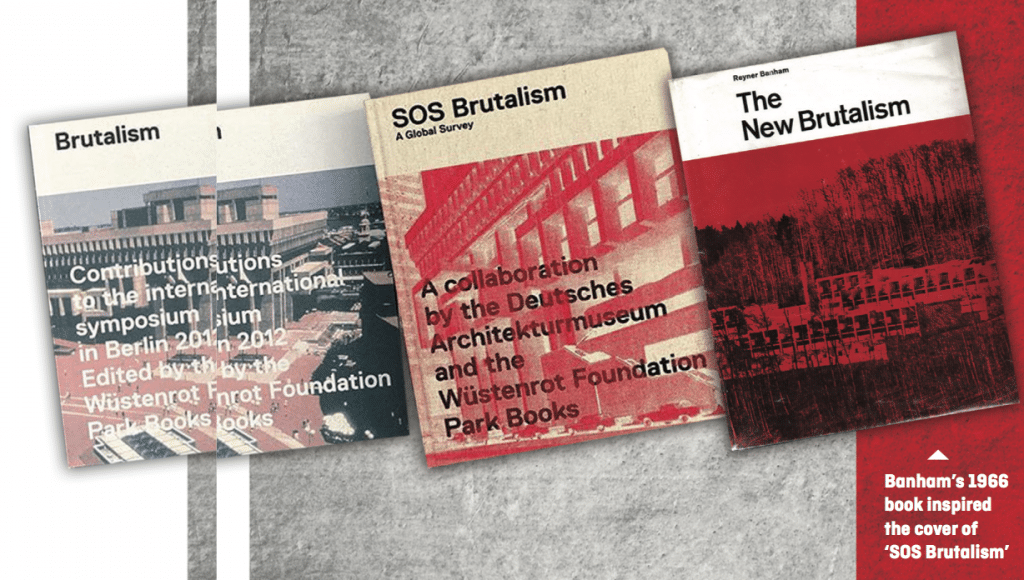

Emma Gilleece reviews ‘SOS Brutalism: a Global Survey’; published by Park Books, 2017 (RRP €68)

‘SOS Brutalism; A Global Survey’ is the first-ever international survey of Brutalist architecture from the 1950s to the 1970s, a collaboration by the Deutsches Architekturmuseum DAM and the Wüstenrot Foundation. It is an understatement to say that this book is a colossal contribution to architectural discourse and twentieth-century conservation. As explored in its essays, even the process of defining this enigmatic genre, still muscular and enthralling after almost 65 years is like grasping wet soap. Each contributor eagerly tries to grip it with the same enthusiasm and excitement that these Brutalist pioneers must have felt when their concrete ‘monsters’ were taking shape. Nevertheless, the debates and divisions are all part and of Brutalism’s contrary appeal.

Cult Status

The godfather of modern architectural criticism, Kenneth Frampton, contextualises Brutalism in the foreword to the book, incisively distinguishing it for example from the“people’s detailing” of the shallow-pitched, tile roofs, cavity brick walls, invariably white “amiable, unchallenging, anti-street, garden-city aesthetic” which “came under therubric of contemporary architecture asopposed to the pre-war notion of a severelyabstract modern architecture”.

The scope of the database of brutalist constructions, contained in an accompanying tome, is staggering: more than 750 pages. It was an important basis for the selection of the book’s 120 case-studies from twelveregions extending to Africa, the Middle Eastand Oceania.

Accompanying the survey are essays from its editors and contributors exploring questions such as whether a building is now Brutalist, or merely a late-modern, exposed-concrete, edifice; the discrepancy between the terms New Brutalism and Brutalism; contemporary efforts to preserve Brutalist buildings across the globe and theassumed continuity debate. The goal of the book is to spotlight the evaluation and preservation of the heritage value of Brutalist works. This is no small task for Brutalism is divisive.

Popular Culture

The compiling of the database sosbrutalism.org by architectural crowd-sourcing, reflects the egalitarian nature of Brutalism mirrored by the role social media has played in Brutalism’s renaissance. For example, think of the international reach to thePreston Bus Station campaign in 2012 which swung its fate from razing to Grade II listing. In recent years Brutalist architecture has achieved a second flowering (cementing?)on social media where its images bulge and captivate. However, there is also a renewed interest in Brutalism in scientific journals, symposia and exhibitions. It appears it’s position in the cycle of fashion and derision is upwardly bound. Perhaps not uncoincidentally, too late for many exemplars.

The database was launched in October 2015 with 250 entries. By September 2017, ithad grown to 1,100 Brutalist buildings, many formerly undercelebrated, of which 120 are endangered through neglect or intended demolition. Experts, architectural buffs and photographers contributed to the survey either by contacting them directly, or by adopting the #SOSBrutalism hashtag.

The Irish Contribution

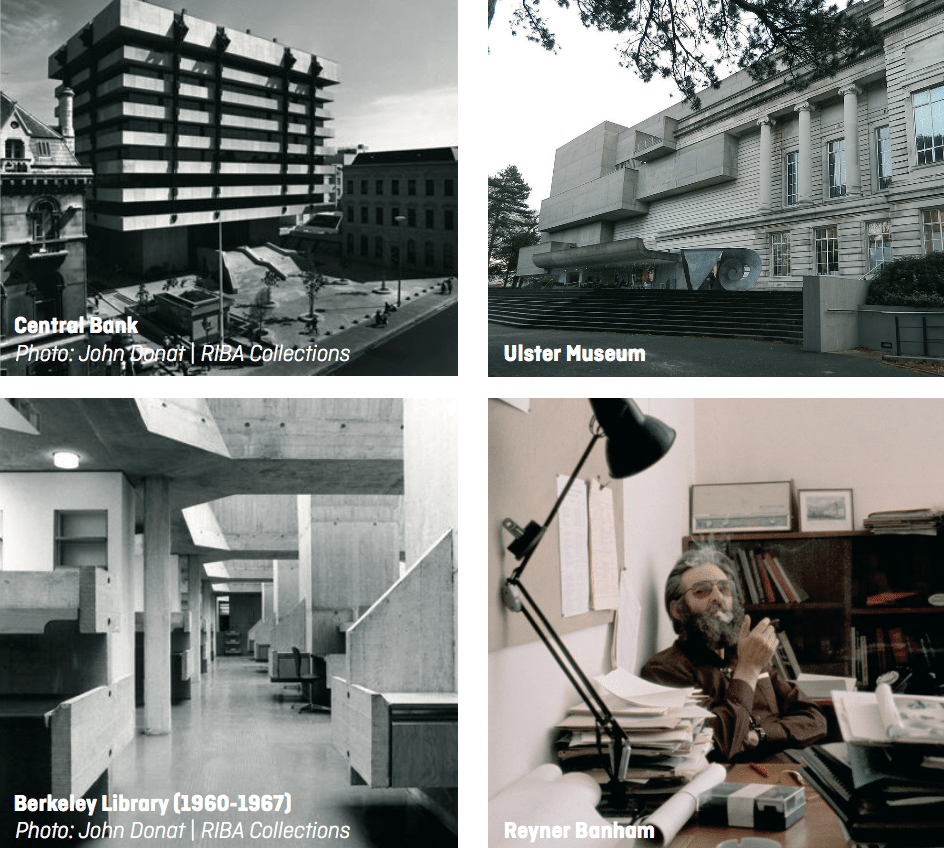

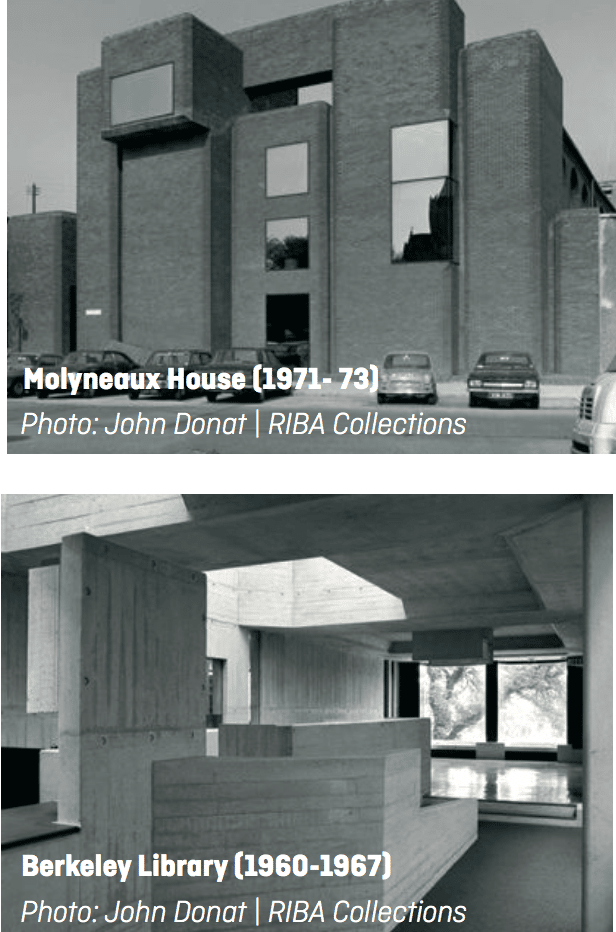

The only Irish case study is Stephenson, Gibney and Associates’ practice head-quarters Molyneaux House, Dublin (1971- 73)written by Erika Hanna. Hanna describes the now anachronistic attitudes not only of that firm but also of Irish planning at that time: “They also publicly delighted in confounding the conservation lobby and were at the center of the most high-profle controversies…demolishing a Georgian streetscape to construct offices for the Electricity Supply Board; building the bunkerish Civic offices on the remains of Viking Dublin;and erecting the Central Bank building higher than its planning permission permitted”.

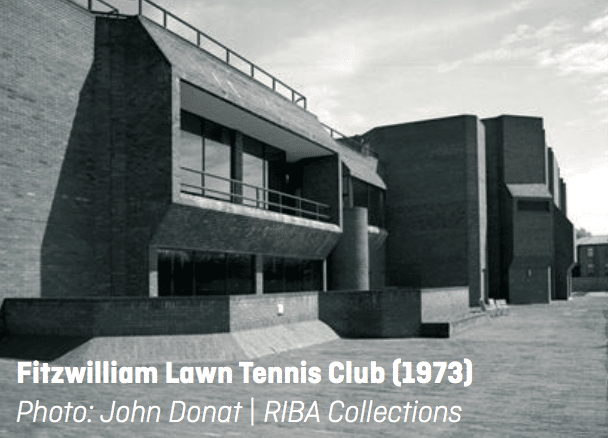

In the endangered list for Ireland they include; the IDA Small Business Centre(1983), by Scott Tallon Walker, highlighted inred as under threat; Stephenson and Gibney’s Fitzwilliam Lawn Tennis Club (1973); and the Ulster Museum Extension by Francis Pym (1962-64).

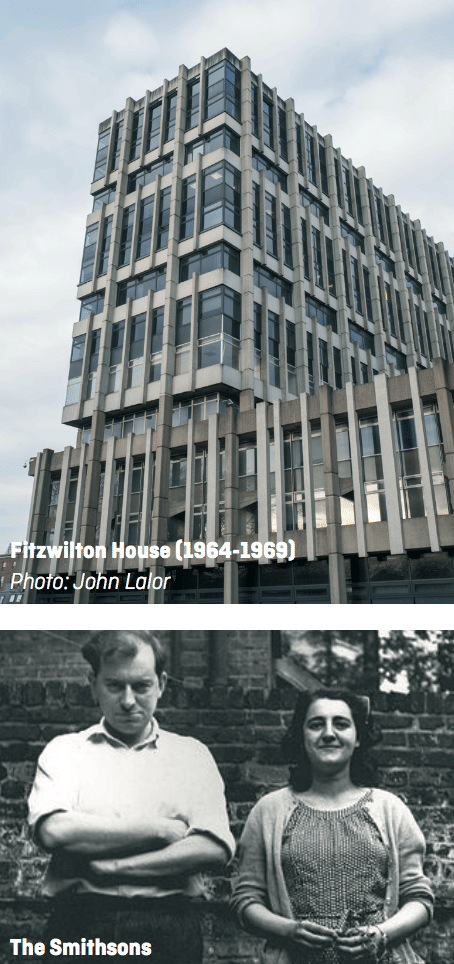

Sadly Fitzwilton House (1964-1969) by Shoolheifer and Burley is in red but will soon be crossed out by demolition. With the refurbishment of the former Central Bank on Dame Street, this book and the publication later this year of ‘More Than Concrete Blocks: Dublin City’s Twentieth-century buildings and their stories, 1940 – 73 Vol. II’ (Dublin, Four Courts Press), no doubt Brutalism will attract new fans overcoming the visceral aesthetic contempt always evident from those with unimaginative good taste.

Design

This hardback is accompanied by a bonus paperback supplement of contributions made to the international symposium on Brutalism that took place in Berlin in May 2012. The retro, voguishly-burlap-bound book perfectlycaptures its scintillating subject era. Many will recognisethe book’s nod to the design of Reyner Banham’s seminal book The New ‘Brutalism: Ethic or aesthetic?’ (1966), the bible of Brutalism which knew, as times were changing, heralded its death. The photographs, both colourand atmospheric black-and-white; sketches; plans andsections make it a joy to turn each page and the list in the Appendix counterpoints the easy joy with evocations of the arresting magnitude of the speed and scaleof loss. The Appendix lists 986 buildings as of September 2017. Threatened/endangered buildings are markedred, demolished buildings are crossed out. Geographic coordinates are provided.

More Than a Catalogue

More than a catalogue, the book’s fantastically researched essays try to define elusive Brutalism, charting its rise and fall and pinpointing its appeal. The movement went beyond aesthetics. These buildings are embedded in the debates of their time when questions of design profoundly refracted a larger political context.Although an international movement, it was regionally-embedded coinciding with a period of decolonisation and nation-building (Africa, Asia), of reconstruction (Europe, Japan), and of rapid modernisation (North/Latin America, Middle East). Wherever we look, Brutalist buildings leered, all over the world, in most political systems.

How many Brutalisms are there? Did the end of Brutalism coincide with the fall of thewelfare state and the beginning of neoliberalism? Did Brutalism become too costly atsome point, because the labour required for customised sculptural products was too expensive? Oliver Eiser’s essay, ‘Just what isit that Makes Brutalism Today so Appealing’,decrees that a new form of Brutalist architecture is long overdue. Annette Busse inher paper, ‘From brut to Brutalism, Developments between 1900 and 1955’, delves into the significance of the difference in the meaning of the words brut and brutal in English, French and German; and into the intellectual and cultural dimension of architects’ designs through their choice of language. Barnabas Calder’s offering, ‘British Brutalisms New and newer’, captures the energy of Brutalism at its zenith in 1970, pulsing thumping new blood back to these concrete brutes: “Many are even more brute-like with organic-looking legs, lumps, and ducts that seem like components of a vast beast.’

Of its Time

The project – SOS Brutalism – aims to cross the border between the expert and the public discourses.

I was disappointed that there were not more Irish entries. However, a crowd-sourcing database is the sum of its contributions so social-media-savvy architectural historians should take collective responsibility. Nevertheless, the breadth and reach of this collection is outstanding, its writers capture the thrill of discovery and – as well as being a banquet for the eyes for the archisexual – it must be remembered that his book is a distress signal to the world. As the global economy is building itself back up in anaesthetic of feigned self-deprecatory modesty, the bulldozers and demolition balls are looming for Brutalism. Without the required heritage-status protection these buildingsare egregiously vulnerable to attack. Brutalas they are.

The book is published in conjunction with the exhibition ‘SOS Brutalism—Save the Concrete Monsters’ at DAM in Frankfurt on Main (8 November 2017 to 25 February 2018) and at Architekturzentrum Wien (3 May to 6 August 2018).

Emma Gilleece

Emma Gilleece is an architectural historian and on the council of DoCoMoMo Ireland