Someone has finally said it. The Cold War is back. The man who made the statement was Antonio Gutierres and he carries some weight on the matter as Secretary General of the United Nations. Up to now most commentators and experts have stopped short of using those two words. They have spoken of a “deterioration in relations” between Russia and the United States and an end of trust between the two countries.

But to those of us who remember the First Cold War certain alarm bells have started to ring. There are people alive today who remember the Cuban Missile Crisis which brought us to the verge of annihilation. In those days both the Soviet Union and the United States had enough weaponry to destroy the planet several times over but the two sides were led by men whose political flexibility served to bring the crisis to an end.

Back then the US was led by John F Kennedy and the leader of the Soviet Union was Nikita Khrushchev. Today both powers can still destroy the world but they are led by Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin. A direct military clash between the two in Syria has been avoided so far and, hopefully, will be avoided in the future but the hostile propaganda that characterised the old Cold War is being used to full effect. As in hot wars the first casualty in cold wars is the truth.

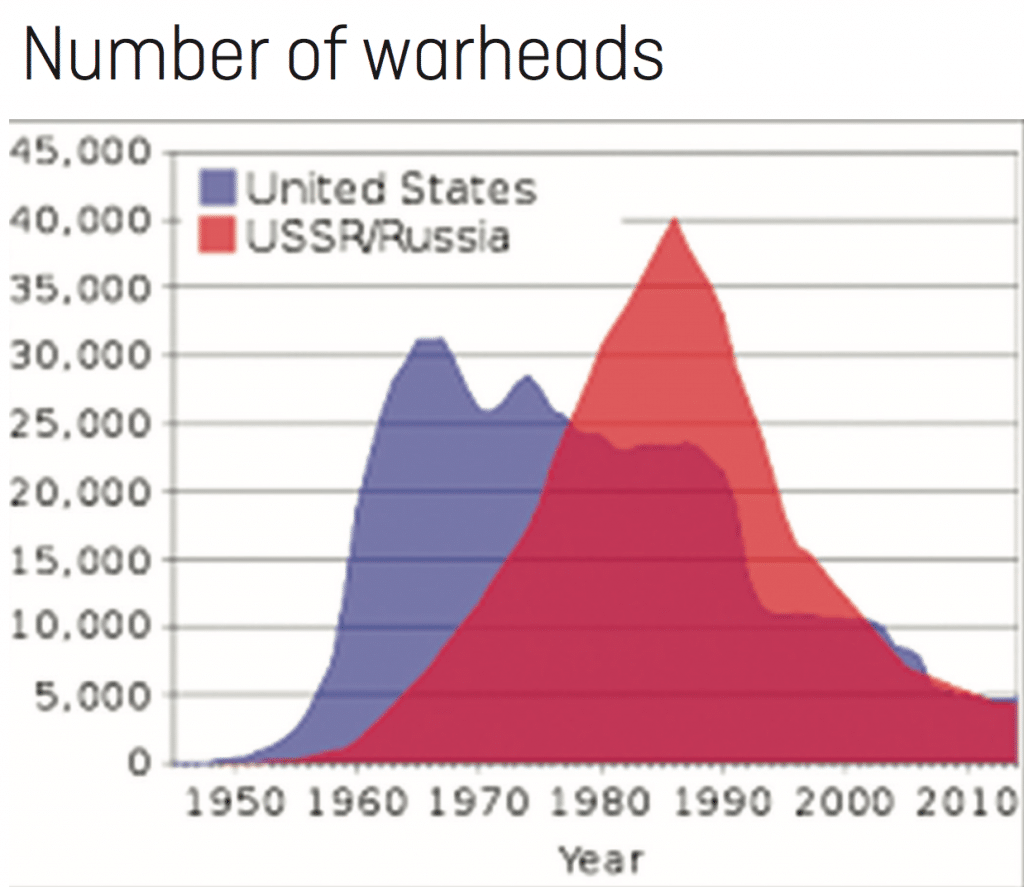

Nuclear warheads remain in both camps but in today’s world a new set of weaponry exists that was unheard of back in the days of Kennedy and Khrushchev. Propaganda used to be issued on radio, TV, the newspapers and, occasionally, from the pulpit. There were lots of opinions doing the rounds but the Soviets saw to it that very little news, fake or otherwise, emerged from their territory.

Back then we were told that the, Soviet peoples, and the Russians in particular, were brainwashed automatons ready to give their lives at a moment’s notice if their leaders asked them to. The Red Army would pour through the Fulda Gap in its hundreds of thousands to end what we considered to be civilisation. Before long we would be as brainwashed as they were and would be ready to do the bidding of our masters.

For me that particular vision of Russia came to an end on a warm July evening in Moscow in 1991. I had arrived a month earlier as the Irish Times correspondent and was settling in to life in what was still the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. On that afternoon my wife and I decided to visit the Novodevichy Monastery one of the city’s numerous historic sites, famous for its beautiful frescoes in the Cathedral of Our Lady of Smolensk.

It was there that we caught our first glimpse of a member of the dreaded Red Army that was all set to annihilate us. What we saw was not what we had expected. The soldier’s appearance was far from terrifying. He was a raw-looking kid in his late teens or early twenties. His uniform cap was slouched back on his head in a manner that would engender the ire of a sergeant in that far less threatening military organisation known to us at home as the FCA.

But that was not all. This boy in uniform was not alone. He walked arm-in-arm with his mother. It was a striking message to us that Russians are as human as we are and in this case perhaps more so.

As for the automatons who believed everything their leaders told them, well that wasn’t true either. There was a burgeoning industry in jokes about the past leader Leonid Brezhnev’s ineptitude. The current leader Mikhail Gorbachev was mocked by sophisticated Muscovites as a country bumpkin with a south-Russian accent.

Workers took things easy under the slogan: “They pretend to pay us, so we pretend to work”. Intellectuals had their own slogan which went: “How can we know what our future is today when we don’t know what our history will be tomorrow”.

Russians didn’t need western propaganda to persuade them that things were not working well. So how have they ended up supporting Putin? The answer has a lot to do with Boris Yeltsin.

Yeltsin brought hope initially but eventually Russia’s economy and its moral compass disintegrated under his rule. Crony capitalism took over from crony communism. Some people became immensely rich while others were selling their belongings in Moscow’s underpasses in order barely to exist. The gun became a major business tool. The Russian Mafia emerged from the shadows and many of its members had backgrounds in the security services. The tradition of the razborka, the settling of matters by the gun, became a major feature of everyday life.

On one occasion that I particularly remember a family visited the grave of one of its members only to be blown to pieces by a bomb planted by a rival group. TV pictures showed the crows picking at human flesh on the branches of the cemetery’s trees.

While this was going on the West indulged Yeltsin. If the 1996 presidential election was rigged then it was done to save the country. If Yeltsin wandered at night in the Washington streets in his underpants it was endearing. If he couldn’t manage to get off the plane in Shannon he was “tired”. Russians knew better. Ordinary people rang the Irish Times Moscow office to apologise for their president’s behaviour. The word stabilnost (stability) was on everyone’s lips.

Then along came Putin. Russians craved stability and they got it. The West’s tone changed. Here was someone who might make Russia strong again. Bit by bit the demonisation of Vladimir Putin began. Relentlessly he was portrayed as the evil emperor. As time went on he helped the propagandists by behaving as they predicted.

We have now reached the stage that any allegations against him are instantly believed. He was responsible for Trump’s election even though it was Cambridge Analytica rather than Russian hackers who did the damage. He was responsible for Brexit because he wanted to destroy the European Union even though Boris Johnson played a much bigger role. His annexation of Crimea was compared to Hitler’s move into the Sudetenland. Turkey’s invasion and continued occupation of Northern Cyprus escaped such a comparison but Turkey belongs to NATO. Media “experts” expound on Putin’s evil nature, his immense wealth and his vast appetite for power even though they can’t even pronounce his name. The “Pewtin” phenomenon has arrived all over the airwaves. Russians support him, we are told, because they are blinkered by a local media which is totally under his control.

Well that is a simplistic analysis. There is a compliant pro-Kremlin media but there are others too. The independent station TV Dozhd, highly critical of the Kremlin, is watched by 17 million viewers. The popular radio station Ekho Moskvy usually gives both sides of every story. There is a corps of Russian journalists that is not only independent but extremely brave.

They braved the violence that entered the journalistic scene in the Yeltsin era and continues to this day. Two of them I counted as friends have been killed. Yuri Shchekochikhin chose a difficult life. He was not only an investigative journalist for the anti-Kremlin newspaper Novaya Gaeta but a member of the Russian Parliament for the pro-western Yabloko party. I used to drink an occasional Armenian brandy with him in his parliamentary office where he would fill me in on the background of the latest political machinations.

Yuri became seriously ill when investigating corruption in a business run by former members of the security services. His death, reminiscent of the attacks on Alexander Litvinenko and Sergei Skripal, has never been satisfactorily explained. It is pretty certain that he was poisoned.

Some years back I visited Yuri’s grave in the Peredelinko cemetery outside Moscow with another journalist friend called Andrei Mironov. In the Russian tradition we raised a glass to his memory. Since then Andrei Mironov has also become a memory. A survivor of the Gulag in the Communistera Andrei was a noted human rights campaigner and also worked for Novaya Gazeta.

He was shot dead, in very questionable circumstances, while reporting on the conflict in eastern Ukraine. Mironov, Shchekochikhin and their murdered colleague Anna Politkovskaya, all from Novaya Gazeta, epitomise the brave and independent journalism that persists in today’s Russia.

This journalism is still there for Russians who want to believe it over the toadying reports of the pro-Kremlin hacks. There are reasons for the continued support for Vladimir Putin other than the populace being brainwashed by an all-powerful pro-Kremlin media.

There has been a striking change in Russian attitudes to their leaders, and sanctions have played their part in that change. Many of those who demonstrated in their hundreds of thousands against fraud in the parliamentary elections of 2011 are now to be found in the Putin camp.

Sanctions may have hit Russians in their pocket but traditionally when under attack from the west Russians rally behind their leader.

Séamus Martin