The Irish Times has had a mixed 1916 commemoration. Even its own audiences seem hardwired to expect a certain bias from the newspaper of reference, but one particular decision – or probably a non-decision no one ever thought to check for unfortunate implications – certainly didn’t help.

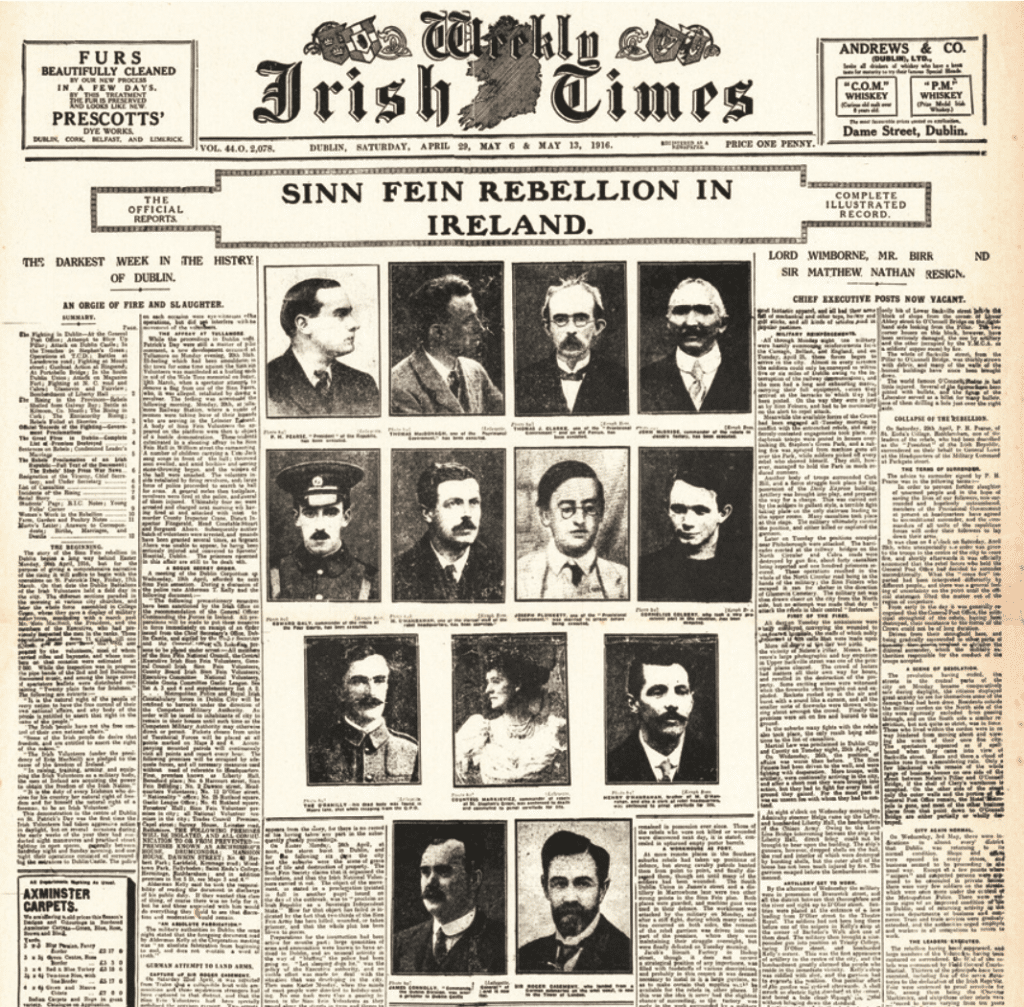

For its 1916 anniversary issue the paper produced a replica cover from 100 years ago, but decided to cut the original banner headline: ‘Sinn Fein Rebellion In Ireland’.

The page-two explanation – that broadsheets aren’t what they used to be, and the resized 2016 dimensions (half the size of the 1916 original) meant the original would no longer t in its entirety and, although it had been shrunk somewhat, any further reduction in print size would render it unreadable, and something had to go… convinced some, but left others unimpressed. If space was the only issue, then why leave two mastheads on the front page, one modern and one vintage?

Assuming the plausible explanation that it was a design decision, and nothing more, the online row it generated speaks much about the perceived trust issues the paper has with its audience. Irish Times journalists are prone to complain that their paper is often held to a higher standard than others, and that may be the case, but it is also a backhanded compliment. Its readers expect more from it, and are therefore more inclined to complain when it does not live up to expectations. The Irish imes garners complaints because what the Irish Times says matters to its in a way that most other newspapers do not. Being an opinion leader comes with a price.

Twitter media accounts come in two avours. There are those that engage, joining in conversations with followers over the stories of the day, even on occasion adding their contributions to the joke of the day on the medium, and there are those that broadcast, casting their bread upon the waters for others to consume, but never acknowledging that the audience is talking back.

Irish Times’ editor Kevin O’Sullivan falls into the latter category. His twitter stream is a list of links to articles he finds it worth highlighting, mostly from his own publication, occasionally from farther afield.

While it is assumed that O’Sullivan curates his own Twitter account, he does not engage with his followers online, or share his thoughts on the news of the day, beyond a brief “interesting” or “scintillating” appended to a story link. And since he does not share his thoughts in detail, the only insight into the thinking of the man helming the paper of record derives from the stories he deems worthy of sharing.

Irish Times 1916 coverage, as highlighted by its editor in the period from Patrick’s Day to the end of Easter Week, was colourful and varied, with thinkpieces by regular and occasional columnists (Fintan O’Toole on Shaw and Casement; Niall O’Dowd on the American input to rebellion; though oddly, no one expurgating the German contribution).

Beyond this, the Irish Times chose to reproduce a letter from Francis Sheehy-Skef ngton to Thomas MacDonagh making a case for pacifism, an offbeat Q&A by cynical Frank McNally: “To question the Rising is to be found guilty of unIrish activity”, Eunan O’Halpin was mean about the Proclamation (“a speech not a Proclamation”), atheist Donald Clarke goaded that it didn’t need to be atheistic, and Miriam Lord wished fervently that we could hold an Easter party every year. Diarmuid Ferriter appeared here and there with as usual more good history than acute insight.

Some ideas that sounded like cringe-inducing embarrassments, such as the new proclamations created by schoolkids, generated genuine wonder. What does it say of a modern nation if children are calling for an end to homelessness while ministers hide behind constitutional guarantees of private property?

On the new-media side, a particular highlight must be the Irish Times’ Women’s Podcast on Margaret Skinnider, volunteer, sniper, school- teacher, trade unionist, and would-be hotel bomber (of the Shelbourne – the newspaper’s readers may have pondered that it might as well have been the Irish Times itself).

The Irish Times has even produced a book called unexcitingly the ‘Irish Times Book of the 1916 Rising’.

And then there was its own 2016 Proclamation, with dodgy prose: “First among our values is the belief that every citizen must have both [sic] the legal, civic [sic] and political rights necessary for full citizenship”, but a progressive core: “we commit our governments to a continuing process of reducing inequality”.

If schoolchildren came out with a simple vision of an Ireland where no one is homeless, the Irish Times’ editorial proclamation for 2016, attempting to cherish all its children equally, had the look of a family Christmas tree, with everyone adding their favourite bauble to the decorations until it became top-heavy, over-owing with good wishes, inclusiveness, and a feelgood spirit that made it look like an out-of-shape heavyweight next to the Spartan declaration of a century ago. Perhaps a little like the Irish Times itself.

Gerard Cunningham