Government should focus on the elderly, as it should have done in March; Varadkar and Martin both outrageously breached the lockdown.

By Michael Smith

Perspective

The Covid-19 infection rate of Irish healthcare workers at 32% of total infections is the highest in the world.

Nursing homes account for nearly two-thirds of deaths, while the international average is just 25%.

Yet those who predicted swamped ICUs, scandalous shortages of equipment and overflowing morgues were utterly wrong. 1800 deaths though tragic, is at the extreme benign end of the predicted spectrum. Annual deaths in Ireland from the flu are 200 to 500.

Nevertheless, we are actually a shocking eighth worst in the world for deaths per million people, a key indicator of incompetence, and indeed of misery, though admittedly we peaked early in global terms and others

will surpass us. It seems a major reason for this is we simply applied the lockdown a week later in the cycle than many other countries.

Media failed

If you haven’t realised all that, nuanced as it is, you weren’t following. Ireland’s media in general failed in their duty to keep the public aware of the evolving pattern of Coronavirus cases in Ireland over the last four months.

There was a pattern of reported cases it is just that the media did not follow it. Their job was not to convey this as a certainty but as the probability, based on the curves – the data. They failed the most vulnerable in society

– the very elderly in nursing homes.

Instead, all their energy went into plying pictures of improvised morgues, invitations to submit stories about deceased love ones, pieces about our nonexistent devastating shortages of PPE and ventilators, and of rockstars organising emergency imports of it. It was implied healthcare workers were dying on a serious scale when seven have died in a sector that employs 120,000 – a rate lower than the average rate for the population and around the same number as that of healthcare workers likely to die in road fatalities and drownings this year.

Figures from the INMO showed that up to the end of May, a total of 8,018 cases of infection of healthcare workers were reported. Some 66 percent or 4,823 remain out sick. New Scientist reported in late June that one in five of those who need ICU treatment may suffer permanent lung damage but that suggests no more than 100 patients in total. Non-mortal infections, even

on a disturbingly large scale, do not constitute catastrophe.

Ireland’s misplaced healthcare-worker catastrophism was enabled by the fact that many countries and in particular the two countries from which we draw most of our external news, the US and the UK, genuinely faced shortages of equipment and facilities and rampant deaths, as well as base, brutal, science-defying incompetence from the very top.

The authorities

Some credit is due to those who imposed the lockdown efficiently (and of course those who observed it – and the healthcare services).

The reality

The rates of infection and indeed of death worldwide have been really quite small (around 360 deaths per million in Ireland; 400 in the US; 700 in Britain, the ignominious world leader, after dysfunctional Belgium).

In Ireland, 65% of cases have come from three sectors: healthcare workers, nursing homes and residential institutions like Direct Provision centres.

The incidences of people outside particular hotspots of this type catching Covid-19 have been low. As to deaths, nursing homes alone account for 62%. And 92% of deaths have been of people over 65 (who comprise just over a quarter of cases; with the median age of death 83), mostly (nearly 90%) with underlying health conditions, “comorbidities”.

Many of these people would have died within a few years anyway. On the one hand, it is the case that it is far worse for younger people with a long life expectancy to die, but on the other, it is extraordinary that it was allowed to happen, with so little real interest in covering the experiences of those in the homes or addressing the predicament of the elderly generally while the virus rages.

The priority for journalism now should be to analyse and draw lessons from what happened in the nursing homes and ensure the most vulnerable, especially the elderly, are better protected against a likely second wave of the pandemic.

Whistleblowers

That is not to say even outside the care-homes all was above board. Village understands there were cases where whistleblowers about potential PPE shortages in hospitals were pressurised to remain silent. An organisation called WhistleblowerAid Ireland has been established to investigate possible corruption surrounding the handling of the Covid-19 crisis. It is affiliated to the charitable legal aid firm which recently advised the whistleblower who triggered the impeachment of Donald Trump.

There should be an inquiry into what happened and major public concern at apparent failures. Guarding a realistic perspective does not mean we should not investigate incompetence.

What happened? Inertia then catastrophism but mainly inadequate regard for nursing homes

Let’s start by looking at the sequence of what happened in Ireland.

There was a very bad start. The Department of Health oversaw a system underprepared for a pandemic and then specifically underestimated the dangers from China – on 20 February the Chief Medical Officer Tony

Holohan ineptly faced a camera and said:

We don’t expect to see anything more than individual cases occurring that we believe we’ll be well-positioned to manage within the next couple of months.

Within a few weeks, however, the official view had flipped the other way and by 8 March Paul Reid, CEO of the Health Service Executive (HSE) was endorsing a report in the Business Post which quoted the health authorities

massively overestimating cases.

The lead story in that newspaper on that day, apparently teed up with the health authorities, predicted 1.9 million infected cases for Ireland which would have implied 68,000 deaths, since the death rate given by the

WHO at the time was 3.4%.

The report did not say there “might” or “would probably” be 1.9 million cases. The word should have been “may” not “will”. It turned out to be dramatically counter-factual. The figures were out by a factor of 60 to 75.

That is the real tale of this plague.

Its best-selling headline on 8 March, a date on which there had been no deaths in Ireland, was “Irish health authorities predict 1.9m people will fall ill with coronavirus”; the subheadline was “Up to 50 percent of cases projected in a three-week period, while the new figures raise fears of intense pressure on health service”. The premise was that we would see 30% daily increases in cases. The smaller print of the report clarified that the prognosis depended on there being no lockdown measures.

The debate in the country seemed for a long time to be premised on the 1.9 million projection, though on one level the Taoiseach swiftly acknowledged that the 30% daily increases lasted only a few days – enough for it to justify the first phase of lockdown. There has overall been a vague (accurate) sense of a battle being won despite (inaccurate senses of) turmoil in the ICUs and,

somehow, the rolling probability of an imminent surge.

It is important to digest the consequences of the central fact that the daily increases in Ireland four weeks after the first salvo at a lockdown here on 15 March, when the pubs were closed, closely reflected those in China four weeks after the lockdown in China on 13 January.

When it went wrong

In an article online for Village on 13 April I predicted that if we continued to follow China

within a week we will have daily increases in cases of no more than three percent and then two percent dwindling to nothing over

the following couple of weeks. There may be a subsequent rise, if we choose to reduce protections, but that is a different matter.

I said it looked like we’d be out of the woods by the middle of May with 35,000 cases and 500-1000 deaths. As of 13 April I updated with the miscalculation that the cases looked destined to be around half that number

while the deaths seem around accurate.

In fact, as of early July we have around 26,000 cases and 1800 deaths from Covid-19, in the first phase, in Ireland.

Nevertheless, 1800 deaths is also at the upmost end of the international spectrum and it is likely there will be many more deaths in a second phase before a vaccine is made widely available.

Overall an informed observer like me in mid-April would have expected around the number of cases we got but half the deaths.

But I did not allow for the scandal of the nursing homes. I did not allow for it because we were misled that they were being handled properly.

For that reason, the useful focus of this article is on the nursing homes.

Nursing Homes Ireland: Visitors and PPE

Nursing Homes Ireland (NHI, a representative though not supervisory group, claims it registered concerns over Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and asked early and often for specific advice on dealing with the

crises but that these calls had not been met with action. For example, on 28 February NHI CEO Tadhg Daly stated “I note the HSE has confirmed in the media there is ‘adequate stock’. This is not the case for our member nursing homes, who require stocks of PPE. We require confirmation of procedures in place to provide nursing homes with stocks of PPE”. On 15 March NHI was reporting:

Members are reporting that suppliers are not in a position to supply as they state they are supplying all such products exclusively to the HSE at this time.

Unfortunately, it seems for the NHI dealing with this PPE seemed the biggest issue. It was not. The Department of Health replied:

We are following the advice of the Chief Medical Officer and NPHET and

will follow-up with them regarding your query.

Department of Health: Visitors

It seems the Department, which always claimed it was following up NHI queries and following medical advice, felt it met its duties by ordering the closure of nursing homes to visitors in time.

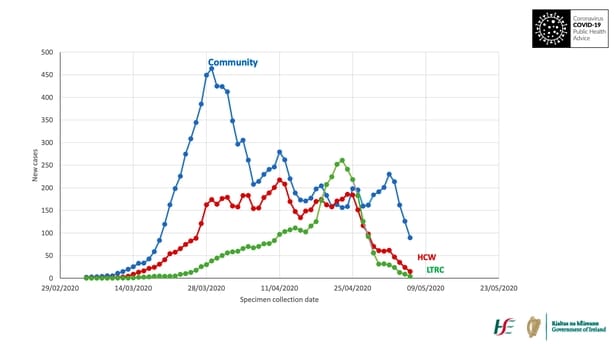

Tony Holohan plausibly justifies that timing on the basis of the epidemiological data contained in this graph which, he says, shows there was a two-week-plus interval between when the visiting restrictions were actually imposed, and when widespread clusters started to emerge in nursing homes, shown in green on the graph.

The graph shows the gap between the last visitors being allowed in and the clusters emerging is too long for visitors to be the problem. He notes that three weeks on from the restrictions being implemented, 40 clusters had emerged in nursing homes. But the vast bulk – more than 400 others – developed after that.

Transfers

On 30 March guidance changed radically from advice given on 10 March: from “test people with symptoms twice before moving them to nursing homes and only move them if the tests are negative”, to “consider testing

people with symptoms after they’ve been moved, but isolate them for 14 days whether they’ve symptoms or not”.

Not that they would be tested but that they would be assessed.

Figures provided by NHI indicate around 1,000 people had been transferred into nursing homes from acute hospitals during February and March. Indeed it may have been a principal determinant for the avoidance of crisis in ICUs – at a price.

Unwittingly carried

The HSE’s Paul Reid told the Oireachtas Committee on Covid-19 in mid-May that “there’s no evidence” to link the transfer of patients to clusters in nursing homes. Crucially there was no mention of symptomless infections.

So the HSE has claimed neither visitors nor transfers led to the care-home crisis. The graph on visitors does seem determinant that they were not a significant source but transfers of symptomless patients seems a likely key source that they are denying.

The Department of Health asserts in fact:

an emerging picture from the accounts from other jurisdictions is that the virus is likely to have [been] carried unwittingly into facilities by asymptomatic or very mildly symptomatic patients or staff, through no fault of either.

What could have been done to pre-empt this?

If the main problem for nursing homes was unwitting transmission that seems to be key to assigning responsibility for the worst of Ireland’s

response generally. Responsibility does not rest with visitors or staff whose role was unwitting, but with decision-makers. Three mistakes are egregious: not asking healthcare staff – many of whom are foreign, underpaid and therefore likely to be living in shared accommodation – and

indeed patients, what could be done to reduce the risk they would transfer infection, failure to supply enough PPE to nursing homes to mitigate spread and failure to test.

Issues with staff and other patients

Systematic efforts should have been made to engage staff and patients about what risks they believed their particular circumstances and contacts

posed to others in nursing homes. For example, anyone living in close quarters to others who were vulnerable or not being tested should have been a focus for testing and isolation.

It appears again inadequate attention was paid to the possibilities of symptomless infections.

Longstanding failure of standards on PPE

The State requires nursing homes to comply with infection control standards set out by the regulator, HIQA. That includes having stocks of PPE. However, few nursing homes were prepared for this, or any, pandemic. It was a symptom of our underprepared health system.

The general failure of PPE in our health system did not cause many deaths, it was the failure of PPE in our nursing homes.

Test care-home staff and patients

Care-home staff and patients could have been tested as the absolute priority of the health system with a view to isolation of those infected. This was the absolute policy priority. But not alone was it not realised at the time, nobody appears to have realised it as the major failure, even ex post facto.

Difficult to obtain tests

On 16 March, the day after the pubs were closed two parallel standards were laid down. In Geneva WHO Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus told a news conference: “We have a simple message to all countries – test, test, test”.

The same day in Ireland the criteria for obtaining a test were changed from ‘having been in an at-risk’ area, or ‘being linked to outbreak’ to ‘having flu-like symptoms in which case rather than the original direct approach of getting a test in a centre you were asked to phone your GP who could refer you for a swab.

The very same day HSE Outbreak Control Teams working in two separate nursing homes first identified clusters.

It was delinquent to have allowed such low testing rates and worse on that date – when the nursing-home problem was emerging – to allow testing to become more difficult to obtain in those homes.

And it was the source of a significant number of deaths.

Late implementation of general new standards on staffing

On 4 April aid of €72m was announced for private nursing homes. Nursing homes applying for financial aid would have to adhere to new policies:

• A major clampdown on agency staff travelling between nursing homes.

• Staff were to be screened for the virus twice a day and have their temperature taken on each occasion.

• Special infection controls teams will be established to liaise with nursing homes and the Health Inspection Quality Authority (Hiqa) will also inspect every residential care facility for older people.

• Preparation of individual plans for tackling Covid-19.

On 17 April it was announced that up to 100,000 staff and residents of long-term residential care facilities were going to be urgently tested. It was much too late. More than 300 had already died in nursing homes and by the time

the tests were complete the crisis had subsided.

Therein lies Ireland’s Covid tragedy and egregious scandal.

Other mistakes

Apart from the care homes of course there were other foolish mistakes most of which I have mentioned in passing: maintenance of a dysfunctional

health service (thought the inflated centralised HSE seems to have found its purpose in this pandemic); underpreparedness; failures to obtain PPE, ventilators and testing reagent in time; general failures of testing and tracking, but they’re no worse than in other countries.

It’s also appropriate here also to query the deal for the HSE to rent private hospitals for an over-long four months from billionaires like Denis O’Brien and Larry Goodman at some ‘costs’ price, agreed to be €110 million monthly. Since there was no market in a lockdown for the elective procedures that are private hospitals’ staple, the hospitals may have been available at lowball prices. The deal, with costs to be approved monthly by EY accountants, will no doubt figure in a formal inquiry. It collapsed and perhaps took with it the prospect of eliminating the second tier of our health system which disappeared, lamentably, from the Programme for

Government, though the new Minister has kept the candle lite. More is probably at stake in that debate than in the whole of Coronavirus.

The media should have explained how the pattern of cases was evolving from the initial 1.9 million projection. They should have then explained that the improvement was because of the effects of social distancing. That would have been the truth and have made the best case for social distancing. They should have documented that failures of nursing-home policy prolonged

and exacerbated the crisis and doubled the numbers of deaths. There was a scandal; just not where they mostly chose to look.

The present and future

Ireland’s social solidarity enabled it to impose a lockdown and maintain it probably rather longer than was advisable when economic concerns and other balancing – including medical – factors are weighed. We should probably factor in the reality that we delayed lockdown by a deathly and disastrous week in March, when assessing how we need to react to the likely ‘second phase’.

Failure to realise what happened in our nursing homes suggests an ongoing policy vulnerability, in circumstances where another wave has started in other countries and is probably going to seriously affect us all for the next years until a vaccine is found and applied.

The lesson is simple: the State needs to obsess about protecting the most vulnerable, particularly the elderly whose will may be weakening, in their characteristic settings, from the next phase.

![]()