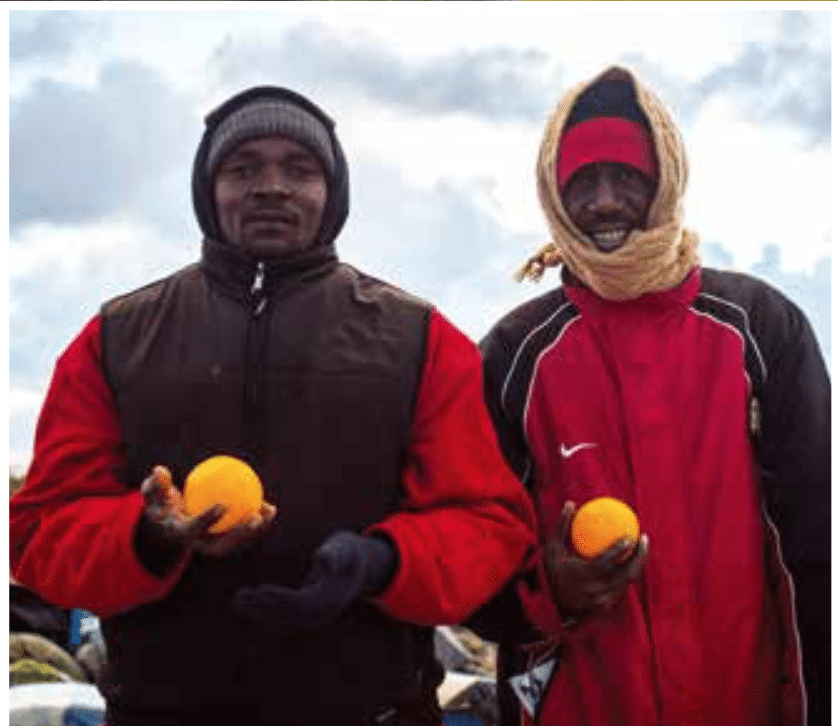

Hundreds of people line up in a queue as soon as the doors of the van open, each hoping to get a pair of warm trousers. It is a cold November day in Calais, but some of them are wearing just shorts and slippers.

In the queue I recognise a Syrian man that I met in the refugee camp on the Greek island of Lesbos just three months ago. He is so thin that it is hard to find him a slim enough pair. But what strikes me even more is his eyes – their sadness and exhaustion – that seem to reflect the cumulation of hardships of the past months, starting in his home country, and now continuing in Europe. That moment of hope and relief, when the overcrowded flimsy rubber dinghy he was on reached the shores of Europe, has now turned into hopelessness at being stuck in one of the worst makeshift refugee camps in Europe, the Calais camp, also known as the Jungle.

It’s not a jungle though: it’s more of a disaster zone. Shabby tents and improvised shelters made out of pallets reach as far as the eye can see. The site is far from ideal for camping, the less so during this chilly rain; the sandy ground has become just muddy. Some parts of the camp are exposed to a heavy wind, and people are looking for help to fix their collapsed shelters. There is no electricity. Sanitation is severely inadequate. No more than 40 toilets are currently serving over 6,000 inhabitants – one for every 150, while the UNHCR recommendation is one toilet per 20 users. With only three taps in the camp, there are not many opportunities to wash hands. Litter is everywhere, and some areas are covered with human extracts.

At one of the two refuse points of the camp I meet representatives of the Médecins Sans Frontières, who have come to collect the rubbish. They remind me to be careful what I touch due to the threat of scabies and other infectious diseases.

A recent investigation by the University of Birmingham, supported by the Médecins du Monde, further highlights detrimental health situations in the camp including the prevalence of ‘white asbestos’, sometimes used to weigh down tenting.

As food in the camp cannot be stored safely, much of it carries infective amounts of pathogenic bacteria, causing diarrhoea and vomiting. Several water storage units exhibit levels of bacteria exceeding the EU safety standards, too. The lack of washing facilities prevents the effective treatment of scabies, lice and bedbugs. Many here are suffering from mental illnesses. The makeshift hospital in the camp has the capacity of treating only up to 90 patients a day and there is a constant shortage of medical supplies. It is especially hard to provide treatment for long-term medical conditions such as tuberculosis. Many patients also come in with serious injuries, often resulting from unsafe conditions in the camp, or failed attempts to cross the border.

I meet a young boy who has a broken arm, after a failed attempt to jump an England-bound train – a typical case.

The United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) has continually expressed about the reception conditions for refugees and migrants in Calais, stressing that security measures alone are unlikely to be effective, and urging the French authorities to relocate the refugees to proper reception facilities in the Nord Pas de Calais region and further afield. Some relief is expected from the proposed EU- supported refugee centre, that is expected to be opened in Calais in 2016. It will reportedly be equipped to deal with 1,500 persons.

Another alternative would be to involve experienced non-governmental aid organisations such as the Red Cross to act as auxiliaries for the public authorities in the humanitarian field. Charities and voluntary organisations offer an invaluable contribution to the current European challenge, but they cannot be expected to supersede the responsibilities of European governments. Of course, permanent aid mechanisms will be required for as long as the conflicts causing the crisis, sometimes exacerbated by Western military interventions, are allowed to continue.

Naiim Sherzai is standing at the exit of the camp, watching the trucks headed for British ports. Sherzai, who comes from the Helmand province in Afghanistan, is a former translator for the British forces, and had to leave the country because of the threat of the Taliban. He now wants to seek asylum in the UK, and ultimately to bring his wife and two children there. He asks whether we could recommend him any legal ways to enter the UK. But in Calais, there are no such routes available for a refugee.

Lack of alternatives drives many to desperate acts, trying to hide in the trucks headed for the ferries or the Eurotunnel, or cutting the fence to hide in the trains. At least 16 people have died this year trying to get across the Channel. Tear gas fills the camp regularly as the police tries to drive out refugees from the proximity of the trucks entering the port of Calais. Although the tightened security measures and border controls have decreased the numbers of those who try to leave, groups of refugees lunge for their freedom every night. The rest, like Sherzai, find themselves lost – the road ahead blocked, but with no turning back either.

In the jungle. In limbo.

Johanna Kaprio