A gunrunner in the family.

By David Burke.

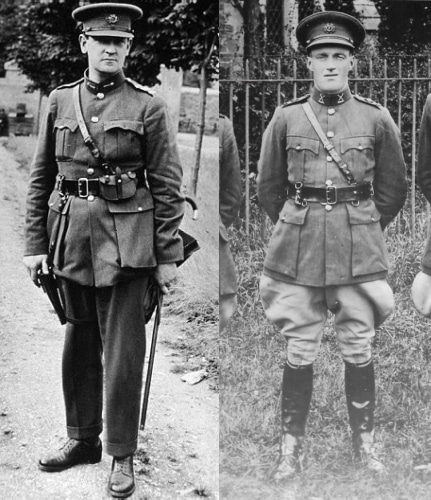

Haughey’s father Seán (on the right) who was one of Michael Collins’ most trusted officers. Collins chose him for one of his most sensitive secret operations.

THE HAUGHEY FAMILY AND THE WAR OF INDEPENDENCE

Haughey’s parents, Seán and Sarah (nee McWilliams), were born and reared almost next door to one another on small farms in the adjacent townlands of Knockaneil and Stranagone, near Swatragh, a few miles from Maghera town in Derry.

Haughey Senior, who was born in 1897, joined the Irish Volunteers in 1917. He rose to become the Second in Command, and later Officer in Command, of the South Derry Battalion of the Irish Volunteers during the War of Independence. At the start of the conflict he carried out raids on the homes of loyalists and a number of retired British army officers.

His military file marked him out as one of the most energetic IRA members in south Derry. In one attack on June 5th 1921, a Royal Irish Constabulary sergeant called Michael Burke was killed while others were seriously wounded in a late-night ambush of the barracks at Swatragh.

As a result of his activities, Seán Haughey had to go on the run. According to his superior, Major Dan McKenna, he would have been killed had he been caught. “His enemies were of the opinion, and indeed not without reason, that he was the cause of all their woes in his area”.

Sarah, who was born in 1901, also played an active part during the campaign as a volunteer in Cumann na mBan. She remained a member until 1923.

Commandant Seán (Johnny) Haughey with his wife Sarah Ann who served in Cumann na mBan.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed on 21 December 1921 and ratified the following January. Yet hostilities persisted in the North.

The UVF began to regroup under Lieutenant-Colonel F. H. Crawford.

Thirty-one people were killed in Belfast between 12 and 16 February 1922.

On 19 March 1922, 200 IRA men surrounded the town of Maghera, County Derry, cutting off the telephones before seizing the Royal Irish Constabulary barracks from which they removed 17 rifles, 5,000 rounds of ammunition and a sergeant as a hostage. The IRA campaign continued the next day with the destruction of mills, sawmills, stables and outhouses in County Derry. Burntollet Bridge (which would become infamous in 1968) was blown up.

On 30 March Michael Collins, representing the Provisional Government in Dublin, and Sir James Craig, signed an agreement. Collins wanted to neutralise the security forces in the North as a threat to the Catholics. In return for a cessation of IRA activity, it was agreed that Catholics should join the Special Constabulary and assume responsibility for policing nationalist areas. In mixed areas, an equal force of Catholic and Protestant officers would be deployed. Meanwhile, all searches would be conducted by mixed units with British soldiers in attendance. The Specials were to wear uniforms with identification numbers and surrender their arms once they had finished their duties so they could be kept in barracks.

On 31 March Royal assent was given to the Free State Bill which became the new constitution of the Free State.

The ceasefire Collins and Craig negotiated proved a failure. On 2 April 500 Specials swooped across County Derry and Tyrone scooping up 300 men for questioning but only four were found to be in the IRA. The rest escaped to County Donegal.

By now the IRA was on the verge of a split into pro- and anti-treaty factions. The 8,500 volunteers who lived in the new State in the North were virtually all anti-treaty. Michael Collins was prepared to supply them with arms for a number of reasons, one of which was that it offered him a possible way to unify the IRA, something that was a priority for him.

SÉAN HAUGHEY PLAYED A KEY ROLE IN MICHAEL COLLINS’ MOST SENSITIVE AND SECRET CROSS-BORDER OPERATION AFTER THE CEASEFIRE

Seán Haughey became involved in what was perhaps the most sensitive and secret covert operation Michael Collins ever mounted: it was one to provide Catholics living across the new border with weapons to defend themselves from the forces of the new state.

Hundreds of Catholics (and many Protestants) had been killed during sectarian riots that had erupted in July 1920. Between 1920 and 1922, 267 Catholics were killed, while 2,000 more would be wounded; another 30,000 people were evicted from their homes and driven from their jobs, especially at Belfast’s shipyards. Collins arranged for guns, at least some of which were supplied by the IRA in Cork, to be smuggled across the Border. Collins was keen not to use any of the weapons he had obtained from the British which could easily be traced back to forces under his control.

The First Northern Division of the IRA in Donegal was led by Commandant-General Joseph Sweeney who went on record stating: “Collins sent an emissary to say that he was sending arms to Donegal, and that they were to be handed over to certain persons – he didn’t say who they were – who would come with credentials to my headquarters. Once we got them we had fellows working for two days with hammers and chisels doing away with the serials on the rifles… About 400 rifles and all were taken to the Northern volunteers by Dan McKenna and Johnny [i.e. Seán] Haughey”. (See also From Pogrom to Civil War by Kieran Glennon.)

Eoin O’Duffy, who later led the Blueshirts, along with Collins and Haughey, was part of the operation to smuggle the IRA guns across the border.

Another IRA man, Thomas Kelly, collected a consignment of 200 Lee-Enfield rifles and ammunition from Eoin O’Duffy. In an affidavit Kelly swore many years later, he revealed that the “rifles and ammo were brought by Army transport to Donegal and later moved into County Tyrone in the compartment of an oil tanker. Only one member of the IRA escorted the consignment through the Special Constabulary Barricade at Strabane/Lifford Bridge. He was Seán Haughey, father of Charles Haughey”.(Michael Collins by Tim Pat Coogan at page 351 Arrow books edition.)

Haughey was also part of another operation which involved making preparations to kidnap political figures in the new Northern state. This involved building an underground bunker of sorts to hold them captive.

The death of Collins on 22 August 1922 brought an end to these operations.

Seán Haughey subsequently joined the Irish Army and rose to become a commandant.

Soon after joining, he was stationed in Co. Mayo. According to Commandant A. Fitzpatrick, in 1923 Haughey and his fellow soldiers had to work in an area which was “almost entirely hostile to the Army”.

They also often found themselves sleeping in the open. “All these hardships endured by NCOs and men had a very detrimental effect on the health of ex-commandant Haughey as he continually endeavoured to improve the conditions of the men under his command, without result”, Fitzpatrick commented later. Their base in Ballina had no heating, lighting or windows.

He was stationed in Castlebar in September 1925 when his third child, Charles, was born.

He retired in March 1928 with a modest pension. He received glowing references from his superiors and colleagues. Major McKenna said of him that he had “done his utmost to make British law impossible in his area”.

After he retired, the family went to live in Sutton, County Dublin, before moving on again to Dunshauglin, Co Meath, where the family took up farming on a 100-acre holding. All told, the couple had seven children: Maureen, Seán, Charles, Eithne, Bridie, Padraig, and Eoghan.

SÉAN HAUGHEY DEVELOPS MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS

The Haugheys with their first born, Maureen.

Haughey Senior developed multiple sclerosis in 1933. He believed that it was caused by the the hardships he endured in the IRA and National Army. He became entitled to a disability pension.

He was forced to sell his farm. In 1933 he moved his family to a small two-storey house, 12 Belton Park Road, Donnycarney in Dublin. By 1935 he was unable to walk. After this, the family had to struggle on in modest circumstances.

His son Eoghan ( brother of Charles ) told a documentary-maker in 2005 that, “My father was an invalid as long as I can remember. In fact I never saw my father working”.

Despite these setbacks, Mrs Haughey managed not only to raise her family but also found time to carry out charity work in her parish with the Third Order of St Francis.

ENCOUNTERS WITH THE B-SPECIALS & THE MAGHERA RIOTS OF 1938

All the while the children were growing up, they received regular visits from relatives and friends from the North with news and stories about what was going on across the Border. In the other direction, the young Charles Haughey spent extended summer holidays in Swatragh staying with his mother’s parents at Stranagone, about half a mile up the mountain road leading from Swatragh.

The holidays took a lot of weight off his father’s shoulders. His uncle Owen McWilliams was a key figure in young Haughey’s development. According to his first cousin, Professor Monica McWilliams, her father volunteered to help rear Charles and his brothers “who would come to the North every single summer”. After his father died, this continued and alleviated the financial pressure on his mother. Owen was a cattle dealer who took Charles and Seán with him to the local fairs.

The boys “became little cattle dealers and little farmers and his helpers every summer until he got married”. They visited such places as Maghera, Kilrea, Tobermore, Desertmartin, Cooktown, Dungiven and Toomebridge. Decades later, Haughey would entertain the Derry minor football team after they had played in an All Ireland final in Croke Park. Several of the team were impressed by his knowledge of South Derry countryside.

The old Haughey family home at Knockaneil, near Swatragh

There was an idyllic aspect to the summer holidays he spent in Swatragh, but some darkness too. On the bright side, Haughey would extol the old McWilliams homestead as “a typical South Derry small farm where they followed what had been the traditional pattern of small farming for generations”. The self-sufficiency of the people impressed him. There was a supply of fresh food with “a nearby bog supplying turf for heating and cooking”. The hearth was the focal point of the house where the fire was never allowed to die out. The fuel for it was the small hard turf the family cut from a local mountain bog they owned. Most of them were involved in cutting it and drawing it back to the homestead with horses and carts.

In notes taken by a cousin, Charles Haughey recorded how: “At night time the last family member had the important task before retiring for the night to rake over the fire. This was done with a tongs and the embers were covered with turf ashes. An early riser would reverse the whole operation, uncover the red coals and using a bellows start-up a bright fire adding fresh dry turf as required. It can, I believe, be confidently stated that this tradition was faithfully followed night after night, and morning after morning so that, in effect, the turf fire in the hearth never went out but was carried on from generation to generation”.

He also helped out on the farm and played with the local football team, and briefly attended the primary school at Corlecky. One summer Haughey and his brother Seán cultivated, pruned and trained the shoots of a sapling to grow into the shape of a horseshoe in the garden in Stranagone. They got the idea from watching the cowboy films they liked so much. His interest in the Wild West was also stimulated by stories his grandfather used to tell about his experiences of the sheep-farming regions of the mid-west of the United States at the turn-of-the-century when he had left.

Violence was still prevalent in the North. In 1935 sectarian rioting had cost eleven deaths and 574 injuries in Belfast.

In 1938, after a visit to the cinema at Maghera, Haughey, his brother Seán and uncle Owen emerged from the building to witness a riot during which Loyalists were firing rifles at unarmed Catholics. The event forged a lasting impression on him. It was, he felt, a visceral taste of what life was like for some Catholics in Ulster; an insight that was shared by very few, if any, of his contemporaries in Dublin, especially the middle-class children he would soon encounter at University College Dublin (UCD).

Haughey was still holidaying in Derry at the outbreak of World War II. He sometimes encountered American troops and army lorries travelling in convoys around the North when he went by train to Portadown or Belfast before continuing his journey by bus to Maghera. In later years he would say that the war had a great impact on him, even more significant than what he had learnt about the civil war.

By 1941 his father had become so incapacitated he was only able to mark an ‘X’ on a statement about his illness.

The young Haughey experienced further sectarian division in the community during these holidays. He and his cousins were sometimes stopped by the B Specials, something he found unpleasant, sinister and often intimidating. These patrols usually intercepted them at night as they were returning to Stranagone. The patrols were made up of men from the neighbouring areas who were known to them, but never friendly; all were drawn from the Protestant community. They were quick to display their authority. Haughey felt there was an element of ‘croppies lie down’ about their behaviour.

One of the reasons Seán Haughey had left Derry originally was because he felt he had become a marked man. His home had been raided in one year on ten separate occasions. Seán Haughey’s father (i.e. Charles Haughey’s grandfather) had to emigrate to the US. He took one of Sean’s sisters with him.

As Charles Haughey would put it, during all this time he “gained at first hand an insight into the manner in which at that time rural communities were firmly divided along sectarian lines”.

To the end of his days Seán Haughey remained a great admirer of Michael Collins and had no time for Fianna Fail. Whether it was a conincidence or not, his son Charles did not join Fianna Fail until after his father had passed away.

Sarah Haughey, a Cumann na mBan veteran of the War of Independence, in later life

There have been rumours for decades that the young Haughey flirted with Fine Gael while in his first year in UCD. While these have never been substantiated, they at least underline the point that Haughey was a much more likely candidate to join it back in times when Civil War politics governed these type of choices.

Charles Haughey would rise to the top of Fianna Fail very smartly, serving in a string of ministries: first Justice, then Agriculture, next Finance. Then, in 1970 he would be accused – falsely – of attempting to smuggle guns illegally with the aid of Irish military intelligence to the IRA. It is diverting to speculate that his father – who would undoubtedly have disapproved of his involvement with the Soldiers of Destiny – might have been buoyed by the accusation – however illusory – that his son was perceived as someone who was following in his cross border arms smuggling footsteps.

OTHER STORIES ABOUT THE ARMS CRISIS AND RELATED EVENTS ON THIS WEBSITE:

RTE’s ‘Gun Plot’: Why has it taken so long for the true narrative of the Arms Crisis 1970 to emerge?

The Official IRA planned the murders of journalists Ed Moloney and Vincent Browne.

[Expanded] British Intelligence must have known that Seán MacStíofáin was a Garda ‘informer’.

Captain James Kelly’s family phone was tapped

The long shadow of the Arms Crisis: more to Haughey’s question than meets the eye

Paudge Brennan, the forgotten man of the Arms Crisis

How the Irish Times got its biggest story of the last 50 years wrong.