As July 1, the centenary of the start of the Battle of the Somme – a asco in which one million soldiers were killed or wounded to make a six-mile advance for the Franco-British forces, comes nearer we will no doubt be asked to counterpose once again the heroism of the Easter Rising participants with the heroism of the combatants in the Great War.

Heroism is surely an ambiguous category. Can heroism in a discreditable cause be admired? Is not indignation the most appropriate retrospective response to the politicians and generals who sent millions to their deaths in that mass slaughter? And compassion, rather than admiration, for those who followed their lead?

The 1500 or so Irish volunteers of 1916 were taking on the British Empire at the height of its power. History has by now justified their cause by passing a negative judgement on that and other territorial imperialisms. The Easter Rising inaugurated the first successful war of independence of the 20th century, an example which many other colonial peoples have since followed. It set in train the events that led to the establishment of an Irish State.

As the world moves from some 60 States in 1945 to 200 today and to a probable 300 States or more over the coming century, it is unlikely that either history or historians will look negatively on that Irish pioneering achievement.

The 1914-18 war was by contrast a war between Empires which unleashed a catastrophe on mankind whose effects still haunt us. Quite apart from its 17 million deaths, 20 million wounded and economic devastation, its disastrous winding-up in the Treaty of Versailles gave us Hitler and World War II.

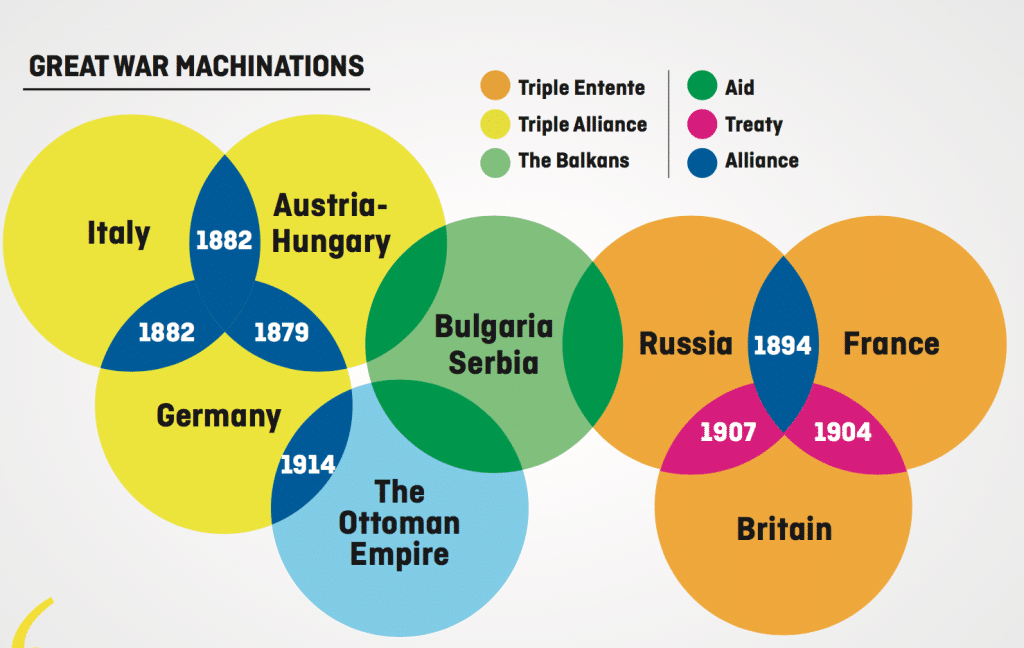

The Great War was a conflict between empire-hungry politicians and powerful economic interests in the main belligerent countries. The recent academic consensus on how it started tends to spread responsibility between on the one hand the governments of the Entente Powers – France, Britain and Russia and on the other the Central Powers – Germany, Austria- Hungary and Turkey. The title of Cambridge historian Christopher Clarke’s best-selling book ‘Sleepwalkers’ implies that both sides drifted into a disaster none of them foresaw or intended. They were all equally foolish or criminal, and so equally responsible.

Traditional left-wing characterisation of 1914- 18 as an “inter-imperialist war” implies a similar conclusion: that as all the imperialisms were bad, they were all equally guilty for the war. It is true there was a war party in each big power on either side. But neither logically nor historically does that mean that they all contributed equally to starting it

Unsurprisingly, Christopher Clarke’s conclusion has gone down well in Germany. Germany was forced to accept sole responsibility for starting World War I in the ‘war guilt clause’ of the Treaty of Versailles. For decades English language historians echoed that verdict complacently until the Australian Clarke came along with his revisionism.

Further revisionism may be called for. Some historians now contend that the prime responsibility for causing War War I rests with Britain. Their thesis seems convincing.

Their argument goes like this: The economic and political rise of imperial Germany from the 1890s onwards threatened British global pre-dominance. German economic competition was making inroads into the British Empire. Britain was a naval power, with a small army. The only powers with land armies strong enough to crush Gemany were France and Russia. They could attack Germany from East and West while the British navy could blockade its ports. The central aim of British foreign policy in the decade before 1914 was to encourage a Franco-Russian alliance against Germany which Britain could join when a favourable moment came.

For centuries Britain’s main continental enemy was France, with which it fought many wars. In 1904 Britain concluded the Entente Cordiale with France, ostensibly to sort out their colonial interests in Africa. This was not a formal military alliance, but secret joint military talks directed against Germany started at once and continued up to 1914.

As for Russia, that was the land of serfdom, the knout and anti-Jewish pogroms in the eyes of British public opinion during the 19th century. Russia threatened Britain’s empire in India. It was the cause of “the great game” between their respective intelligence services, which Kipling fictionalised in his novel ‘Kim’. Britain and France fought Russia in the Crimean War of the 1850s to prevent it moving in on the weak Turkish Empire to take Constantinople and the Dardanelles, which was a longstanding Russian dream.

In 1907 Britain upended this policy and came to an agreement with Russia on their respective spheres of in uence. From that date British policy-makers worked together with France and Russia towards bringing about a war with Germany in which Turkey would be pushed into joining Germany’s side. If victorious, France would get back Alsace-Lorraine, which it had lost to Germany in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870. Russia would get Constantinople and the Dardanelles. And Britain, France and Russia between them would divide up the rest of the Turkish Empire, including Syria, Lebanon, Palestine and Iraq.

The war aims of the Entente Powers were set out in the secret treaties which the Bolsheviks released in 1917 following the Russian Revolution. These tell us what ‘the war for small nations’ was really about – that of cial propagandist phrase which many people in this country who do not know their history are still liable to trot out to explain Britain’s involvement in the Great War.

Who were the British politicians who orchestrated this scheme to crush Germany for a decade prior to Sarajevo? They were the ‘Liberal Imperialists’ who were in office from 1906 – Asquith as Prime Minister, Grey as Foreign Secretary, Haldane as War Minister and Churchill as Naval Minister, interacting intimately with the Tories’ Arthur Balfour, Alfred Milner and Bonar Law, for the key people on both front benches were at one in their anti-Germanism.

And what of poor little neutral Catholic Belgium – leaving aside its bloody Congolese appendage – the German attack on which in 1914 was the ostensible reason for Britain going to war? It is clear that in the month following Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s assassination at Sarajevo Britain deliberately prevaricated on what it would do if Germany sought to invade France through Belgium. Coupled with Britain’s seeming preoccupation with the Ulster crisis at the time, this led Germany to think that Britain would stay neutral – and Foreign Secretary Edward Grey sedulously sought to give that impression.

A German assault on Belgium was necessary to get British public opinion – and importantly the bulk of Government Liberal Party opinion, much of which was strongly pacifist, on side for the planned war. It is a myth to think that there was a legal obligation on Britain to go to war if Belgium’s neutrality was violated. Gladstone had not thought so. The 1839 Treaty of London which recognised the independence and neutrality of Belgium was not a treaty with Belgium but a treaty about Belgium. Belgian Governments had been engaged in joint military planning with their French and British counterparts for a war with Germany for years. The Entente Powers had long taken it for granted that Belgium would be militarily involved.

Two recent books set out the detailed case for Britain’s prime responsibility for causing World War 1. One is by two Scottish historians, G Docherty and J Macgregor, ‘Hidden History: The Secret Origins of the First World War’ (Mainstream Publishing, Edinburgh). The other is by Dr Pat Walsh, ‘The Great Fraud of 1914-18’ (Athol Books, Belfast). They will revolutionise most people’s understanding of that event.

Germanys’ war aims

Of course Germany had its war party too. The continuity of German elite aspirations up to our own times can be seen from the notorious September 1914 programme of Kaiser Wilhelm’s imperial Chancellor, Theobald Von Bethmann Hollweg, when he declared Germany’s war aims to include: “Russia must be thrust back as far as possible from Germany’s eastern frontier and her domination over the non-Russian vassal peoples broke… We must create a central European economic association through common customs treaties to include France, Belgium, Holland, Denmark, Austria-Hungary, Poland and perhaps Italy, Sweden and Norway. This association will not have any common constitutional supreme authority and all its members will be formally equal but in practice will be under German leadership and must stabilise Germany’s economic dominance over Mitteleuropa”.

Anthony Coughlan

Anthony Coughlan is Associate Professor Emeritus of Social Policy at Trinity College Dublin