62 people now own the same wealth as the poorest 3.6 billion people. 1% owns more than 99%. The gaps are widening.

Talk of overseas aid may seem like trying to use a sticking plaster to plug a haemorrhage. In a world of trickle up economies with ever growing needs driven by conflict and climate, aid remains critical. Despite the critiques of aid in the past decade, without it, many of the Least Developed Countries, would collapse.

This Government is not without achievements in Official Development Assistance (ODA). Following the financial crash in 2009, the aid budget was an easy target and was slashed by 30% in the 2010 budget. Those affected by cuts in the aid budget are not visible and certainly won’t arrive at Leinster House on their tractors. Several Irish NGOs were also downsized and their aid programmes closed as a result.

Following that significant cut, however, the aid budget was stabilised at around €600m. This was made possible by cross-party support and opinion polls which showed the tacit support of the public.

Over 80% of people in Ireland regularly state they are in favour of aid. They may not raise it on the doorsteps, but they see it as the right thing to do.

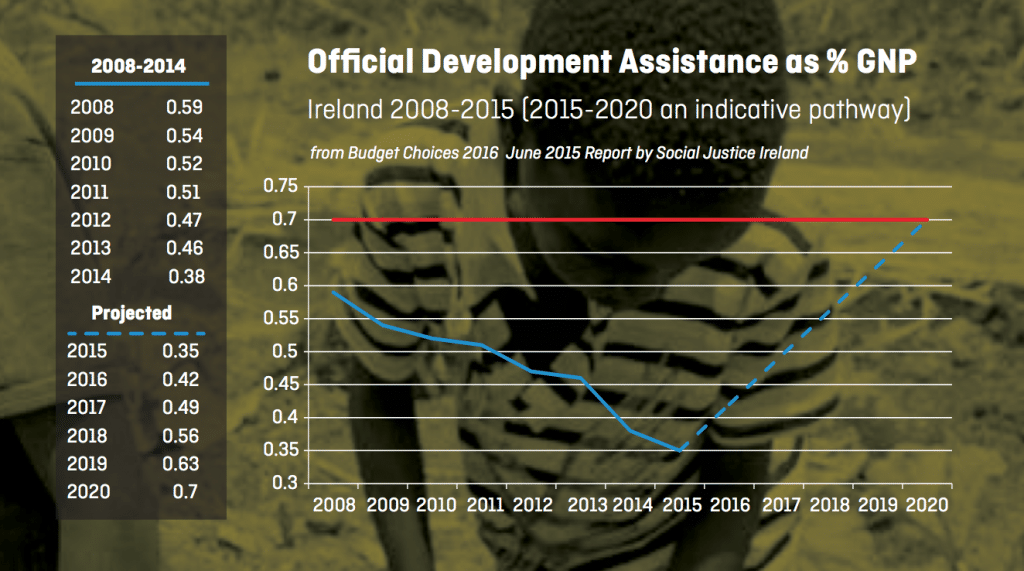

On the other hand, all OECD countries are committed to giving 0.7% of Gross National Income (GNI) in ODA and we have failed to reach this target. The commitment is a long-standing gold standard in international development and one which many countries had been close to achieving before the financial crash. In 2009, Ireland was giving 0.59% of GNI in ODA.

The target, as a percentage, is set up to be cyclical. Countries will give according to their means as their economy expands and contracts.

The commitment to reach the 0.7% target was in the Programme for Government of the current Government, with a target date of 2015. However, there has been no real commitment. The economy is now growing yet the aid budget has remained at. We increasingly and significantly lag behind the OECD target.

Our aid provision now stands at 0.38% of GNI, the same as in the early 2000s.

A new commitment to reaching the target within the life time of the next government is essential.

Significant improvements have been made in the quality of Ireland’s aid programme over the lifespan of the current Government. International trends reflect shifts towards concessional lending and private-sector engagement. However, Ireland’s aid programme has become more poverty-focused. This is both in country focus, with one of the highest rates of funds going to Least Developed Countries, and in the types of programmes it funds. The aid programme has bucked the international trend of skewing aid to serve the needs of the donor country and has remained highly poverty-focused.

‘One World, One Future’, the Irish Aid policy, was launched in 2013 following a public consultation. It sets out Ireland’s priorities in overseas development. The commitment to addressing hunger is clear.

The current Government spearheaded the drive to address hunger globally and led on international initiatives such as ‘Zero Hunger’ at the UN. It has become a leader in this area and ensured that this initiative was central to the new Sustainable Development Goals signed in New York last September.

Questions have been asked, however, about the involvement of Irish Aid in the corporate- backed Global Alliance for Climate Smart Agriculture, which has received much criticism from global civil society, and attempts to link this to the hunger agenda. The biggest gap, however, is the failure to embed the priorities for development in all government departments. While both the Irish Aid Policy, and the ‘Global Island’ policy, the core foreign policy statement, boast commitments to development and human rights as a “whole of government effort”, little has been done to implement it.

This incoherence is stark. As Ban Ki Moon, the UN Secretary General said during his visit to Ireland last May: “One cannot be a leader on hunger, without also being a leader on climate change”. Coherence demands that our commitment on global hunger is matched by a commitment to funding programmes for climate adaptation and resilience matched with equal effort to reduce our own emissions.

Aid remains essential. However, if aid is to be effective it requires commitment as well as joined-up thinking across all policy areas. This challenge must be addressed by the next Government.

Lorna Gold

Lorna Gold is Head of Policy and Advocacy with Trócaire