The new Minister for Social Protection will face a number of significant challenges. She has to deal comprehensively with the damage of the immediate past, while expediting long overdue reforms, and at the same time stay on top of new welfare challenges associated with changing forms of family, employment patterns, demographic trends: all betrayed by pervasive inequalities.

The UN has provided some valuable guidance for the new Minister – in the Concluding Observations of the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights on the third periodic report of Ireland about implementation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights of June 2015. The Committee strongly advised that austerity policies should only be temporary and only cover the period of the crisis. They recommended that Ireland restore pre-crisis levels of social protection. They stated that Ireland must strengthen policy capacity with a disaggregated data strategy and adequate rights and equality-proofing mechanisms.

Five key priorities for the new Minister for Social Protection are suggested:

- Redressing the impact of austerity cuts on children at risk of poverty, young people under 26, and lone parents. These groups suffered serious collateral damage from austerity budgets that failed to protect the vulnerable;

- Reversing reductions in welfare payments that left recipients below the poverty line;

- Tackling long-term unemployment in a manner that promotes inclusion in the labour market for all those who want employment, including people with disabilities, and all women;

- Ensuring the contribution of social welfare payments to the growing crisis in family homelessness.

- Changing the male breadwinner model and responding to new forms of family diversity.

The universal Child Benefit was reduced over a number of austerity budgets from €166 per month in 2010 to €130 pm in 2013, with additional cuts to the higher payments for the 3rd + child. This payment was increased by €5 over budgets 2015 and 2016 and is now €140. The combined impact of these cuts and parental unemployment means child poverty doubled over the crisis period. Social-welfare-dependent single families with children suffered cumulative cuts over the crisis. The number of jobless households with children also burgeoned. Tackling child poverty is far more complex than simply restoring child benefit to its pre-crisis level. The new Minister must take seriously the advice offered by the National Economic and Social Council (NESC0 and by various commissions and expert groups. A tiered and better targeted child-income-support system is a prerequisite for efficiently tackling child poverty but avoiding unnecessary unemployment and poverty traps.

Austerity disproportionately damaged the young. Its mechanisms included emigration, deterioration in the quality of employment and severe social welfare cuts – with job-seekers’ allowance reduced by more than half for those under 25 (from €204 to €100). Many young people have emigrated to avoid not only poverty and unemployment but also low-quality employment and underemployment; others remain trapped in the parental home unable to afford the transition to independent adult life or to move to larger urban centres to seek employment. An immediate priority is resolving the situation of the 600 young people who, unable to sustain residential tenancies on such an inadequate income, are left dependant on emergency homeless services.

The new Minister should revisit the previous Minister’s overzealous cuts to lone parents’ income disregards, and the decision to compel lone parents, once their youngest child is 14 years old, to work full-time. It is clear that this policy is not conducive to the wellbeing of parents or children. Various creative alternative reform proposals have been offered to promote a more positive reform agenda capable of addressing poverty and respecting parents’ choices for reconciling care work and paid employment.

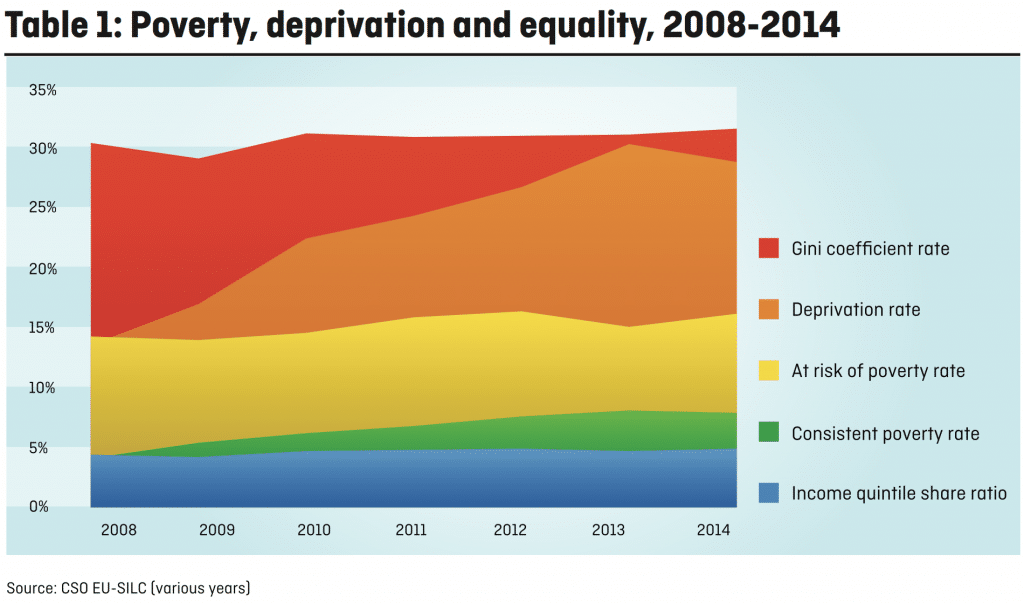

While the EU Survey of Income and Living Conditions (SILC) shows poverty, deprivation, consistent poverty and inequality rose over the crisis (Table 1), Watson and Maitre (2013) still nd high levels of efficacy in Irish social transfers. Despite social welfare cuts, Irish welfare payments were relatively effective in cushioning people from the worst effects of rising unemployment and falling incomes. Social transfers reduced the post-transfer poverty rate by 53% in 2004, but this rose to 71% by 2013.

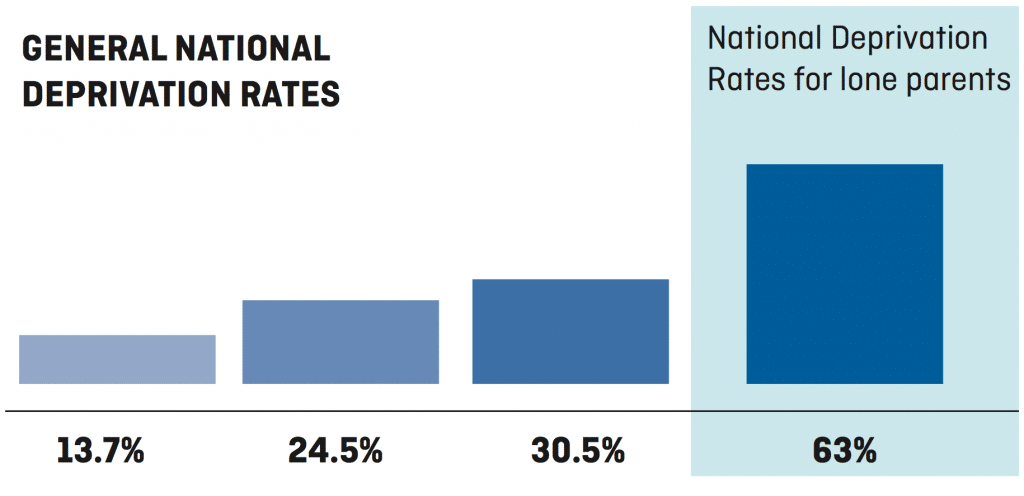

Despite such an impact, deprivation rates still rose from 13.7% to 24.5% between 2008 and 2011, and up to 30.5% in 2013 before decreasing. Deprivation rates for lone parents, however, peaked at 63% in 2014 (CSO). The NESC has outlined the significant social impact of the crisis (2013). It estimated that 10% of the population experience food poverty. There is growing use of ‘soup kitchens’ and runaway homelessness.

The welfare system is the core mechanism for economic equality. There are, as Micheál Collins argued in last month’s Village, lessons to be learned from mistakes in previous recoveries where the failure to prioritise welfare increases saw social-welfare-dependent households’ fall dramatically behind general incomes. The new Minister must commit to, and budget for, adequacy and indexation of all social welfare payments, not just those considered ‘deserving’. These increases need to be a policy priority, not crumbs – or an afterthought.

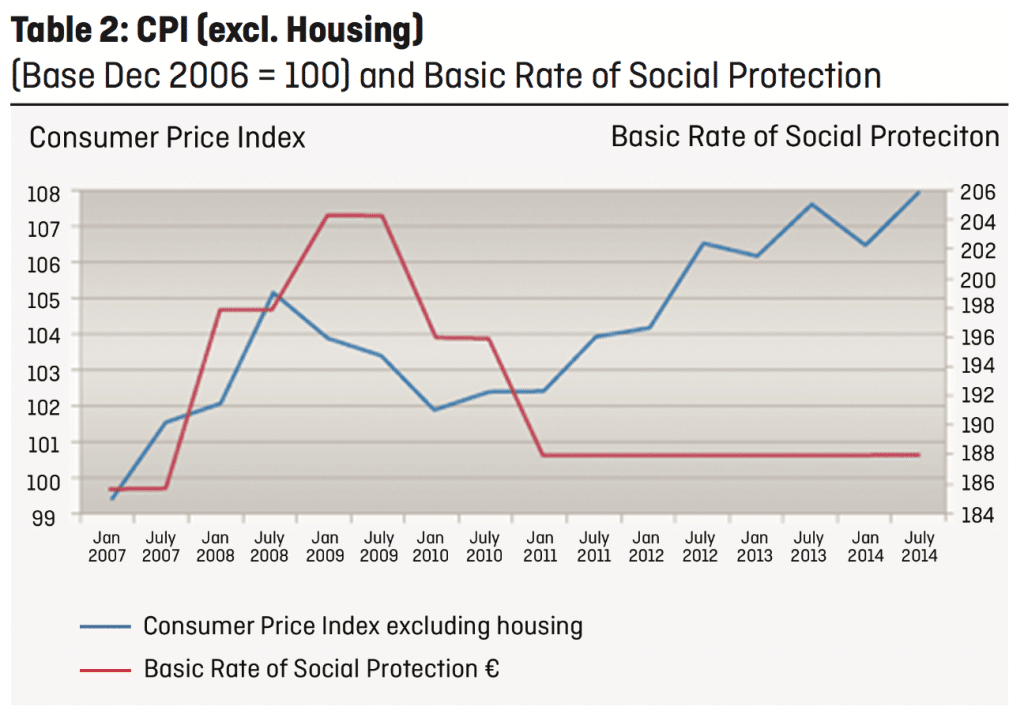

Since 2011 social welfare rates have not been decreased except for two social welfare cuts which decreased the adult working age payment by €16. As Focus Ireland recently observed these cuts coupled with an increasing cost of living, have resulted in a considerable erosion of living standards for those reliant on social welfare payments as can be seen in this comparison of recent increases in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) with stagnant Irish social welfare rates (Table 2).

The last five years have seen an unprecedented level of reform in the State’s employment services, in particular merging institutions into INTREO. The Pathways to Work 2016-2020 policy document does acknowledge services are struggling to reach quality standards, with uneven service delivery and poor guidance capacity. Other capacity gaps are now being addressed by ‘Job Path’, private-sector services for the long-term unemployed. These are based on a ‘pay-by-results’ model which will probably increase pressure on people to take poor-quality employment.

The new Minister must carefully consider whether this work- first activation model is the best approach to active inclusion for everyone, including people with disabilities and all women who want to work. The new Minister must learn from other failures of the 1990s. Tackling long-term unemployment required institutional reforms and investment in tailored, personalised services for those most disadvantaged in the labour market. Making work pay requires regulating for decent work and against poor-quality, low-paid employment.

The decision to freeze Rent Supplement levels in 2013 has directly contributed to the growing crisis of family homelessness in Dublin and elsewhere. Inadequate rent caps leave families and individuals on low incomes unable to compete for accommodation with people in employment; and unable to pay market rents. Families sink further into poverty as they dig deeper into their own resources to increase the rent supplement to a level adequate to cover realistic market rents.

A poverty and unemployment trap occurs as families are unable to obtain or maintain rent supplement when one adult in the family is in employment, even though the income from employment is clearly insufficient to meet the rent. The new Minister must prioritise implementation of the planned Housing Assistance Payment (HAP) where local authorities effectively rent from private land-lords and subsequently use employment-neutral rents to lease on the properties to people in housing need. In the meantime one of the Minister’s first acts has to be to increase rent caps and the levels of rent supplements.

Finally, the new Minister must introduce a social-welfare reform agenda that changes the old male-breadwinner Irish welfare system to enable it to meet the challenge of new forms of family diversity and social risks. This means revisiting the agenda of individualisation and equality of access to enabling supports. An adequate and universal individualised old-age pension must be part of this reform agenda.

Mary Murphy

Mary Murphy lectures in Irish Politics and Society in NUI Maynooth.