Commemorations for the centenary of the 1916 Rising are well underway. This anniversary is being marked in a much less sanitised way than previous significant Easter Week commemorations. This is very welcome. For far too long, ceremonies celebrating the 1916 Rising were based on a highly simplified, monochrome account of history: Rebels good, Brits bad, civilians ignored. We did not see pictures of dead bodies. Few official accounts mentioned the deaths of women and children caught in the crossfire. This time around, things are different.

The vital research work of many historians and others has contributed greatly to the generation of this more complex understanding of the 1916 Rising. We now know that approximately 488 people were killed during Easter Week. Of these, 40 were children, and over 200 were civilians. There were about 120 British soldiers killed, and 60 rebels. These numbers are as significant as the numbers we have traditionally associated with commemorations marking Easter Week: the seven signatories of the Proclamation, and the 16 men executed.

It is timely to reflect on four key themes which should shape, and to some extent are shaping, the centenary commemoration process: de-militarisation; contextualisation; inclusivity; and humanisation.

Commemorations should not be over-militaristic, nor should any death or killing be ‘celebrated’. This is even more necessary in the wake of the recent Brussels atrocity which showed the immense human tragedy of mixing religion, politics and violence. The events organised throughout Dublin for Easter Monday under the ‘Reflecting the Rising’ banner were far more in keeping with an inclusive spirit of commemoration, than the military parade that took place on Easter Sunday.

In a similar spirit, commemorations should reflect the context of the time. The rise of important social movements, in particular the trade union and suffragette movements, as well the Irish cultural revival, should be marked alongside the nationalist struggle.

The commemorations must be inclusive. Where official ceremonies include religious services, these must be carried out with respect for humanists, atheists and people of minority religions. Similarly, commemorations must be inclusive of both women and men. We now know, from the great work of feminist historians, that 77 women involved in the 1916 Rising were arrested along with their male colleagues at the end of Easter Week. Inclusivity also means remembering the many thousands of Irishmen who fought and died in World War I, but whose lives and deaths were not officially commemorated for many decades after independence.

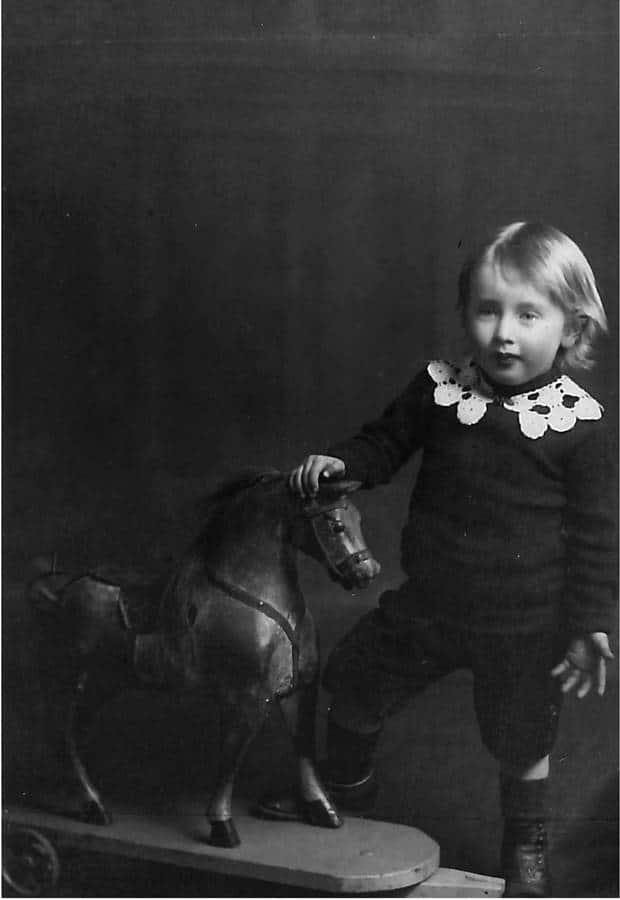

Commemorations must become humanised. It is welcome to see this happening in this centenary year. Many official and unofficial events have incorporated the telling of individual eye-witness accounts: some noble, some tragic, some humorous, and some poignant. These include stories like that of Catherine Byrne, who jumped through a side window of the GPO to join the male Volunteers inside. They include that of two-year old Sean Foster, who was shot dead in crossfire while being wheeled in a pram by his mother Katie on Church Street, and whose father had died on the Western Front the year before. In bringing these stories to the fore, we come closer to realising the past and to remembering the dead in a respectful and inclusive way.

It is very welcome to see these four themes informing the 2016 commemoration process. Yet it appears that they are not embraced universally. The Glasnevin Cemetery Trust has carried out hugely important work in compiling accurate data on all the 488 people killed during the 1916 Rising. It is constructing a Necrology wall to mark all of their deaths in a non-judgemental fashion. It is unfortunate that some of the 1916 Relatives Association do not support this approach to commemoration. And that there was some scuffling at the recent unveiling.

It seems that, for them, even 100 years on, there is still a hierarchy of grief. Those who still seek to elevate some deaths over others are themselves harking back to the old monochrome view of Easter Week. Their view should not prevail.

The reality is that the concept of ‘commemoration’ is always problematic. Ultimately, we should not seek to replace ‘history’ with ‘commemoration’. Commemoration is a largely artificial concept, itself tending towards sanitisation. History is messy, complex, ambiguous and contradictory. The history of the 1916 Rising should be marked and remembered in a way that is appropriate to that reality. Accurate historical research, inclusive contextualised events, and vivid eye-witness accounts should replace empty commemorative ceremonies.

Our process of marking the 1916 Rising should be de-sanitised, to reflect the real complexity of the history of the struggle for Irish independence.

Ivana Bacik