Two recent events highlight the true nature of the ongoing Irish economic recovery. Firstly, ahead of the infamous Ireland-Argentina Rugby World Cup match, the press office of the main governing party, Fine Gael, produced a rather brash infographic. Charting projected growth rates in real GDP for 2015 across all Rugby World Cup countries, the graph put Ireland at the top of the league with 6.2 percent forecast growth. “FACT: If the Rugby World Cup was based on economic growth, Ireland would win hands down”, shouted the headline.

Having put forward a valiant performance, the Irish team went on to lose the game to Argentina, ending its incipient ascendancy.

Secondly, within weeks of publication, Budget 2016 – billed by the Government as a programme for the ‘New Ireland’ – has been discounted by a range of analysts, including those with close proximity to the State, as representing the return of a fiscal policy of …electioneering. Worse, judging by the public opinion polls, even the average punter out there has been left with a pesky aftertaste from the political wedding cake produced by Merrion Street on October 13th.

Tasteful or not, the public gloating about headline growth figures and the fiscal chest-thumping that accompanied Budget 2016 did not stretch far from reality. Official growth is roaring, public finances are in rude health, and the Government is back in the business of handing out candies to kids on every street corner. The air is filled with the sunshine of recovery and talk about the Celtic Tiger Redux is back on the menu for South Dublin along with the fennelised lamb.

Ireland by the numbers

On budget day the government projected full-year 2015 inflation-adjusted growth of 6.2 percent followed by 4.3 percent in 2016. Extraordinarily optimistic, “one minister acknowledged that the growth figure for this year is likely to end up nearer to 10% than the 6.2% estimated just 6 weeks ago”, according to a story on the front page of the Sunday Business Post in late November. Much less optimistic, the IMF has the figures at 4.9 percent and 3.8 percent, respectively.

Still, this ranks Ireland at the top of the advanced economies’ growth league, with second place Iceland at 4.8 percent and 3.7 percent, respectively.

The only other advanced economy expected to post above 4 percent growth in 2015 is Luxembourg. Which is dramatically telling: of all euro-area member states, the two most exposed to tax optimisation schemes are growing the fastest. Though only one has a Government gushing publicly about that fact. No medals for guessing which one.

The problem is: the headline official GDP growth for Ireland means preciously little as far as the real economy is concerned. The reason for this is the composition of that growth by source and, specifically, the role of the Multinational Corporations trading from Ireland. We all know this, but keep harping on about the said ‘metric’ as if it mattered.

Based on the figures for the first half of 2015 (the latest available through the official national accounts), the Irish economy grew by €6.4 bn or 6.9 percent in real GDP compared to the first half of 2014. Gross National Product, or GDP accounting for the officially declared net profits of multinational companies, expanded by a more modest 6.6 percent over the same period.

Other distortions arising from this structural anomaly at the heart of the Irish economic miracle are the effects of foreign investment funds and companies on the capital side of the National Accounts. Back in 2014 the European Union reclassified R&D spending as investment, superficially inflating both GDP and GNP growth figures. Since then, our investment has been booming, outpacing both job creation and domestic public and private sector demand. In more recent quarters, capital investment has been outperforming exports growth too. Which compels a question: what are these investments about if not a tail sign of corporate inversions past and a forewarning of the changes in the pattern of economic output in anticipation of our heralded ‘Knowledge Development Box’?

Beyond this, the legacy of the financial crisis has compounded the artificiality of growth statistics. Irish ‘bad bank’, Nama, and its vulture-fund clients are aggressively disposing of real estate loans and other assets bought at regrettable cost to the taxpayer. Any profits booked by these entities are counted as new investment here. Once again, GDP and GNP go up even if there is virtually nothing happening to buildings and sites which are being flipped by these investors.

And while we are on the subject of the old ways, last month Ireland was announced as the domicile of choice for an upcoming merger between Pfizer and Allergan – two giants of the global pharma world. Despite numerous claims that Ireland no longer tolerates so- called ‘tax-driven corporate inversions’ (a practice whereby US multinationals domicile themselves in Ireland for tax purposes), it appears that we are back in the old game. Just as we are apparently back revenue shifting (another corporate tax practice that sets Ireland as a centre for the booking of global sales revenues despite no underlying activity taking place here), as exemplified by the Spanish Grifols announcement earlier in October. Just when we thought we were out they pull us back in!

All of these growth sources also benefit from the weaker euro relative to the dollar and sterling, courtesy of ECB printing presses.

Looking at the national accounts for January-June 2015, Gross Fixed Capital Formation accounted for €3.8 bn or almost 60 percent of total GDP growth over the last 12 months, and nearly three quarters of total GNP growth.

In simple terms, the real economy in Ireland has been growing at closer to 3.5 or 4 percent annually in 2015 – still significant, but less impressive than the 6-percent-plus figures suggest.

exchequer kindness

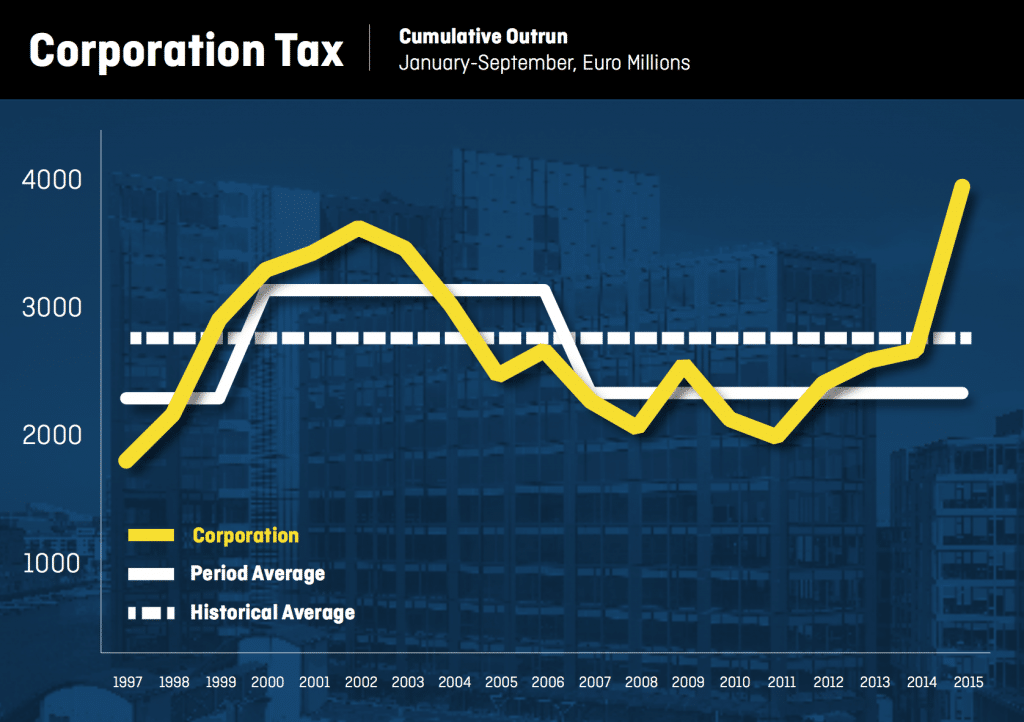

Still, the above growth has worked well for the Irish Government. In the nine months up to September 2015, Irish Exchequer total tax receipts rose a strong €2.75 bn, or 9.5 percent year-on- year. Just over 45 percent of this increase was due to unexpectedly high corporate tax receipts, up 45.7 percent year-on-year. One source quoted in the Sunday Business Post in late November predicted the figures for November would be “off the charts”.

VAT receipts increased €742 m or 8.3 percent year-on-year, while income tax posted a more modest rise of €677 million up 5.7 percent. While both VAT and Income Tax receipts came in within 1-2 percentage points of the budgetary targets, Corporation Tax receipts overshot the target by a massive €1.21 bn or 44.2 percent.

As the chart shows, in the first nine months of 2015, Corporation Tax receipts have not only out-performed the trend for 2007-2014 and the historical average for 2000-2014, but posted a massive jump on the entire post-crisis ‘recovery’ period. Both the levels of tax receipts and the rate of annual growth appear to be out of line with the underlying economic performance, even when measured by official GDP growth.

This prompted the by-now-famous letter from the outgoing Governor of the Central Bank, Professor Patrick Honohan to the Minister for Finance in which the Professor politely, almost academically, warned the Government that a large share of the current growth in the economy is accounted for by “distorting features” – a euphemism for tax-optimising accounting: “Neglecting these measurement issues has led some commentators to think that the economy is back to pre-crisis performance”.

Professor Honohan’s warning reflects the breakdown in sources of growth noted earlier, with booming multinationals’ activity outpacing domestic economic expansion.

The same is confirmed by the recent data from labour markets. For example, whilst official unemployment in Ireland has been declining over the recent years, labour force participation rates have remained well below pre-crisis averages and are currently stuck at the crisis period lows. In simple terms, until very recently, job creation in Ireland has been heavily concentrated in a handful of sectors and professional categories.

Of course, this column has been saying the same for months now, but for Irish official media, the voice of titled authority, is still awaited.

The Revenue attempted to explain the Exchequer trends through October, but the effort was half-hearted. According to Revenue, the €800m breakdown of Corporation Tax receipts outperformance relative to target can be broken into €350m of the “unexpected” payments; €200m to “early” payments; and €200m to “delayed” repayments. Which prompted the conclusion that the surge in tax receipts was “sustainable”.

Turning back to the fiscal management side of national accounts, Irish debt-servicing costs at the end of 3Q 2015 fell €296m- or 5.9 percent compared to January-September 2014. The key driver of this improvement was refinancing of the IMF loans via market borrowings and, of course, the ECB-driven decline in bond yields. Neither is linked to anything the Government did.

Spurred by improving revenue, however, the Government did open up its purse. Spending on current goods and services (excluding capital investment and interest on debt) has managed to account for just under one tenth of the overall official economic growth in the first half of 2015. In other words, even before Budget 2016 was penned and improved revenues shimmered on the horizon, Irish austerity has turned into business-as-usual.

Talking up the future

As a result of the tangible economic recovery – albeit that it is more modest than official GDP figures suggest –Budget 2016 unveiled in w marked a large-scale about-turn on years of spending cuts and tax hikes. Even though the Government deficit is still running at 2.1 percent of GDP and is forecast to be 1.2 percent of GDP in 2016, the Government has approved a package of tax cuts and current-spending increases worth at least €3bn next year. The old formula of ‘If I have it I spend it’ is now replaced by the formula of ‘If I can borrow it I spend it’.

Which means that in 2016, Ireland will run a pro-cyclical fiscal policy for the second year in a row, breaking a short period of a more sustainable approach to fiscal management. Another point of concern is the fact that this time around, just as in 2004-2007, expansionary budgeting is coming on the back of what appears to be a one- off or short-term boost to Exchequer revenues. Finally, looking at the composition of Irish Government spending plans, both capital and current spending and multi-annual public investment include steep increases in spending allocations of questionable quality, including projects that potentially constitute political white elephants and electioneering.

In short, the Celtic Tiger is coming back. Both the best side of it and the worst.

Constantin Gurdgiev