By David Burke.

This article was first published on 2 July 2021. It is republished to mark the 50th anniversary of the publication of Lord Widgery’s infamous report which defamed the victims of Bloody Sunday and exculpated those who murdered them.

1. Brigadier Frank Kitson subverts the law.

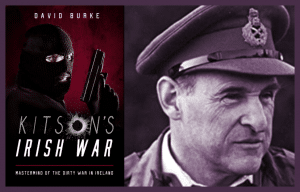

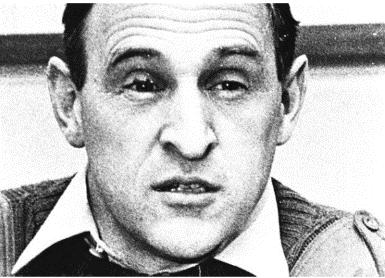

Brigadier Frank Kitson of the British Army was a so-called counterinsurgency guru. He was sent to Northern Ireland in 1970 to tackle the IRA. The following year his astonishingly indiscreet book, ‘Low Intensity Operations’ was published. In it he explained that there were two ways of administering the law during a counterinsurgency, the first one being that:

the law should be used as just another weapon in the government’s arsenal, and in this case it becomes little more than a propaganda cover for the disposal of unwanted members of the public. For this to happen efficiently, the activities of the legal services have to be tied into the war effort in as discreet a way as possible … The other alternative is that the law should remain impartial and administer the laws of the country without any direction from the government. [Kitson (1971), p. 69.]

The first tribunal investigating the events of Bloody Sunday – Widgery – is a good example of how the law was used as “just another weapon in the government’s arsenal”.

On Monday 31 January 1972, Tory Home Secretary Reginald Maudling announced in the House of Commons that there would be a judicial inquiry into the Derry massacre. That evening British Prime Minister Ted Heath and Hailsham, his Lord Chancellor, asked Lord Chief Justice Widgery to chair it. Widgery had been a surprise appointment as Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales by the Tories the previous year. He was not viewed as a jurist of the first rank by his peers. His career was one which would ultimately descend into bedlam. Private Eye magazine would report that “he sits hunched and scowling, squinting into his books from a range of three inches, his wig awry. He keeps up a muttered commentary of bad-tempered and irrelevant questions – ‘What d’you say?’, ‘Speak up’, ‘Don’t shout’, ‘Whipper-snapper’, etc”. [Private Eye Issue 436, 1 September 1978.]

These comments were published two years before he stepped down from the bench. The view expressed by the Eye is reflective of Widgery’s reputation for having been ‘difficult’ by members of the Bar in Britain. ‘Difficult’ in this context is a polite euphemism. Widgery was despised by the legal profession which viewed him as a second rate political appointee who strove to conceal his shortcomings in the traditional manner of the lower tier judge: by hectoring, pelting and bullying.

2. Judicial compromise

The night before Heath asked Widgery to conduct an inquiry, he had expressed his belief to Taoiseach Jack Lynch that Kitson’s paratroopers had behaved properly in Derry. If Heath truly believed what he had said to Lynch, he had an unusual way of showing it. He chose Widgery – a safe pair of hands – and left him in no doubt that he was to pervert the course of justice. At the meeting on 31 January Heath told Widgery that it “had to be remembered that we were in Northern Ireland fighting not only a military war but a propaganda war”. It is hard to conceive of a more compromising comment made by a British prime minister to a senior member of the judiciary, let alone the man at its pinnacle. No matter what way one looks at it, the comment demonstrates a breath-taking lack of esteem on the part of Heath for the independence of the judiciary. Yet Widgery did not rise to his feet and leave the room in protest. Instead, he did what his master bid him to do.

3. An Allegedly Independent Judge pre-judges the Murder Victims by Attending a Meeting at which they were referred to as ‘the other side’

At the same meeting at which Heath had given Widgery his riding orders, the parties to the discussion had also referred to the victims as the ‘other side’. [Para (viii) of minute of meeting of 31 January 1972.] Moreover, according to confidential notes by a Widgery associate, the “LCJ” [Lord Chief Justice] could be counted on to “pile up the case against the deceased” even though the evidence provided “a large benefit of the doubt to the deceased.” [‘Hidden Truths’ (1998), p. 95.

4. Threats to Muzzle the Ever Compliant British Media

In the days after the massacre, the journalist Murray Sayle and his colleagues completed a report which was submitted to the Sunday Times. There was internal opposition to its conclusion, namely that Colonel Derek Wilford, who had led 1 Para in Derry on Bloody Sunday, had set out to provoke the IRA into coming out into the open so his troops could wipe them out.

Harold Evans, the editor of the paper, decided to ring Widgery. “I said we had done a great deal of interviewing and proposed to publish this Sunday. We also had compelling photographs. I told him I presumed contempt would not apply since nobody had yet been accused. It would be an exaggeration to say he was aghast, but he made it very clear it would be ‘unhelpful’ to publish anything and yes, he would apply the rules of contempt. .. I withheld the article, but that week I took the chance of publishing the shocking photographs by Gilles Peress of unarmed men being shot”. [Harold Evans, ‘My Paper Chase, True Stories of Vanished Times’ (Little, Brown and Co, New York, 2009), p 474.]

On Sunday 6 February, the paper reported that, “The law is that until the Lord Chief Justice completes his enquiry nobody may offer to the British public any consecutive account of the events in Derry last weekend”. [Sunday Times 6 February 1972.]

Heath’s press office rowed in declaring that anything which anticipated the Tribunal’s findings would amount to contempt. This was a highly contentious assertion without precedent to underpin it: there had never been a prosecution over media investigations in such circumstances. The edict led to a report by The Observer being suppressed too. It would have contained a detailed reconstruction of the day’s events. [Liz Curtis, ‘Ireland the Propaganda War, the British Media and the ‘Battle for Hearts and Minds’ (Pluto Press, London 1984) p. 48.]

5. Black Propaganda

As Widgery’s appointment was being announced in the House of Commons, on 1 February, the British Information Services (BIS) began distributing a document entitled, ‘Northern Ireland: Londonderry’ in the US. It claimed that ‘of the thirteen men killed, four were on the security force’s wanted list… One man had four nail bombs in his pocket… Throughout the fighting that ensued, the army fired only at identified targets – and attacked gunmen or bombers… The troops came under indiscriminate fire’. There was not an honest word anywhere in the statement. The most blatant lie was the passage referring to the wanted list which was subsequently withdrawn.

Widgery was not disturbed by the BIS document. It did not amount to contempt in his eyes. On the contrary, with the exception of the reference to the wanted list, the BIS document served as the template for his eventual findings.

6. John Hume wanted an “independent authority” to conduct the inquiry

John Hume and others wanted to oppose Widgery. Hume was of the “firm opinion” that an inquiry would only be acceptable if it was conducted by “an accepted independent authority”.

Dr Raymond McClean, a civil rights activist and doctor from Derry felt that:

a senior European or American judge should preside, preferably in a neutral location, for example in nearby Donegal in the Republic, which would be convenient for witnesses to attend. They hoped that if the families stood firm, this could be achieved. ‘I was extremely disappointed, he wrote later ‘to hear that a group of the local clergy, headed by Fr Mulvey, had made a public statement in favour of attendance at Widgery, and that the immediate families were in agreement with their statement. Our case for a truly independent enquiry had been sterilised at birth. Many important witnesses were then in a serious quandary as to what decision they should make as regards attendance at Widgery. [McClean (1983), p. 139]

The families were handicapped by Widgery from the outset. He appointed one silk and one junior to represent the thirteen dead (as the figure then stood), and those wounded by bullets, not to mention the scores beaten with rifle butts and abused on the streets and brutalised at Fort George in Derry.

7. Fabricated Evidence

All of the families but one co-operated with Widgery in good faith. They had no idea what was taking place in the background. For a start, fabricated evidence was being generated. A captain who served as a medical officer on Bloody Sunday, known by his cipher, 219, spoke of “Another thing that upset me after Bloody Sunday was the briefing prior to the Widgery Tribunal”. He has also stated that:

On my return to the battalion I was assembled, and briefed, with a large number of other officers and men in a hall in Palace Barracks. In the hall we were briefed on what to say and how to say it. The briefing was conducted by members of the battalion (I do not remember who) and by strangers from outside who I believe were lawyers. I do not know whether they were Army or civilian lawyers. I remember sitting there feeling very upset — they were almost putting words into our mouths. I was very upset at the time and even now it upsets me.’

Regrettably, the manipulation of evidence was taking place on an industrial scale. There were substantial material discrepancies between what the soldiers first said and what appeared in their statements. Professor Dermot Walsh, the Chair of Law at University of Limerick and the Director of the Centre for Criminal Justice, undertook a meticulous examination of the soldiers’ statements which revealed that there were three objectives to the exercise: {i} the erasure of implausible allegations, {ii} the making of statements which corroborated each other, and {iii} the removal of comments which had the potential to lead to accusations of murder. [Walsh, Dermot P.J, ‘Bloody Sunday and the Rule of Law in Northern Ireland’ (Gill and Macmillan, Dublin 2000)] Some of the statements had been changed up to four times. This information was known to the lawyers acting for the Tribunal but not to those for the families.

The only honest paratrooper to have emerged from the storm of lies that have swirled around Bloody Sunday since 1972 is Byron Lewis. He told a similar tale to that of the doctor. It fits perfectly with Professor Walsh’s findings.

There followed a long period of waiting while confined to Hollywood (sic) Barracks during which time we underwent several searching interviews by the S.I.B. One morning a Sioux helicopter landed in the parade ground and whisked me – Soldier 027 – up and away across Northern Ireland to Coleraine. Again there was the same contrast as my “fateful trip to Derry”. A beautiful sunny day, fabulous views of the countryside. Loch Neagh stretching away into the distance. On arrival in Coleraine we flew along the river which runs through that town and sat down between some trees outside the court house, where the Tribunal was in progress. Disguised and escorted I was led hunched up through a mob of waiting pressmen and reporters, and shown into some offices within the building. Here there were a number of soldiers from my Platoon, all disguised as I was and we spent some time pouring over aerial photographs along with the S.I.B trying to establish which shots had been fired by whom and from where what a farce, we were all grinning at each other and drawing lines haphazardly all over the place with the result that the authorities finished up with a series of sophisticated looking spiders webs, which bore no relation to fact. I was then interviewed in an office by two Crown lawyers on Lord Widgery’s team. I rattled off everything I had seen and had done. The only thing I omitted were names and the manner in which people had been shot, apart from that I told the truth which I wanted to convey. Then to my surprise one of these doddering gentlemen said ‘dear me Private 027, you make it sound as though shots were being fired at the crowd, we can’t have that can we?’ And then proceeded to tear up my statement He left the room and returned ten minutes later with another statement which bore no relation to fact and [I] was told with a smile that this is the statement I would use when going on the stand. What a situation! The Lord Chief Justice of Great Britain, the symbol of all moral standings and justice having his minions suppress and twist evidence, with or without his knowledge who can tell? I was amazed!

8. Lord Saville gave Widgery’s Lawyers a Clean Bill of Health

The thought that officials of the former Lord Chief Justice had engaged in such a reprehensible manipulation of the Widgery tribunal was too much for Lord Saville to stomach. Saville was the judge in charge of the second tribunal into Bloody Sunday that began in 1998 and reported in 2010. When he examined this issue, he rejected what Lewis had to say. In the eyes of Saville, it was Lewis who was the culprit, not Widgery and his team. “In our view”, Saville propounded, “what is likely to have happened is that Private 027 [i.e. Lewis] felt that he had to invent a reason to explain providing a statement for the Widgery Inquiry that was inconsistent with his later accounts; and chose to do so by falsely laying blame for the inconsistency on others”. [Saville Report Chapter 179, paragraph 26 contained in Volume 9.]

Unfortunately, this is but one of a number of examples of the type of shallow thinking Saville occasionally slipped into, inspired perhaps by a reluctance to countenance that members of his profession and class were capable of such deceit. Yet, it is abundantly clear that the soldiers of Support Company of 1 Para lied to both him and Widgery and, clearly, Saville accepted and knew that this was a fact. This being so, how did he think they managed to coordinate such a massive deception without help? If the sham was not overseen by some of Widgery’s officials, then by whom was it perpetrated?

Did it not occur to Saville that if no less a figure than the Chief Justice was prepared to take on the brief in circumstances where Heath had given him his riding orders, it was conceivable that he hand-picked or was supplied with officials who were prepared to deliver the desired outcome: a clean bill of health for 1 Para and the commanders and politicians above them.

The treatment of Byron Lewis by Saville left a bad taste in the mouth of many. Mickey Bridge, one of those shot on Bloody Sunday, felt that the account of how his statement had been rewritten for him for Widgery was “glossed over at the Inquiry”. He has said that:

In fact, his own side tried to discredit him. There were one or two others who also said the statement they got back in 1972 was constructed for them and all they did was sign it and it was not true. [E. McCann (2006), p. 100.]

9. Widgery’s Wiles

Widgery treated the truth as a volatile substance and engaged in subterfuge to prevent it exploding in public. First, he rejected Heath’s offer to sit with others which meant he was in total control of the proceedings which were duly heard in Coleraine. He followed this by narrowly defining the terms of reference for his inquiry. He would merely examine the events which took place on “the streets of Londonderry where the disturbances and the ultimate shooting took place” over “the period beginning with the moment when the march… first became involved in violence and ending with the conclusion of the affair and the deaths”. This meant that he could ignore anything which pointed to a plan to encroach upon the Bogside, including the type of material which The Sunday Times had discovered and suppressed. It also meant that an array of MI5 officers such as David Eastwood, ‘Julian’ of MI5, ‘James’ of MI5 and others attached to the intelligence services would not be troubled. (They testified later at Saville).

Another Widgery wile was to exclude witnesses. Dr McClean, who had attended to many of the dying and wounded and gathered evidence of the use of illegal dumdum bullets, decided to offer himself as a witness to Widgery despite his reservations. McClean has described, how:

After much discussion and formal examination of my prepared evidence, the officials informed me that my presence would not be required at the inquiry – this, despite the fact that I was one of only two medically qualified persons on the spot. I had examined and treated the first two casualties shot, had examined four of the dead at the ‘scene of the crime’, and had been appointed by Cardinal Conway to represent him at the postmortem. Dr Kevin Swords, the only other medically qualified person present who had treated one casualty at the scene, was called to give evidence, and this was only, according to the Widgery Report, to establish whether or not Gerald Donaghy had anything in his pockets. [McClean (1983), p. 140.]

By excluding McClean, the doctor’s observations about the use of dumdum bullets were suppressed.

10. A High Speed, Drive-by, Tribunal

Another ploy was to conduct what can best be described as a high speed, drive-by, Tribunal. Widgery sat for a mere seventeen days between 21 February and 14 March 1972 during which he heard one hundred fourteen witnesses. The number was an illusion. Only thirty of them were Derry civilians, with some of the central ones being omitted.

Joe Mahon was arguably the single most important witness available to the tribunal. He had watched the cold-blooded murder of Jim Wray in Glenfada Park at close quarters. He was not called to testify. The RUC were complicit in this. Mahon, then sixteen, has explained how, when he had been in hospital after the shooting, RUC officers came to his room. “One was a wee fat detective and I said then that I had seen a man getting shot by a soldier, and the policeman said to my father, ‘It would be better if that boy said nothing at all’. That was it. I was never called to Widgery.” [McCann (2006), p. 102.]

Only seven of the wounded by gunfire appeared before the Tribunal. “I did not think it necessary to take evidence from those of the wounded who were still in hospital”, was the excuse Widgery provided in his report for ignoring their evidence.

Contemporaneous recordings were excluded too. James Porter ran a television repair shop. In his spare time, he was a radio enthusiast. So skilled was he, he had managed to monitor and record British army communications on the day from the back of his shop. He handed his recordings over to Peter Pringle of The Sunday Times, who, in turn, offered them to Widgery, but they were rejected on the basis that they had been recorded illegally. [‘Hidden Truths (1998), p. 59-60.]

11. A Mountain of Written Evidence was Ignored by Widgery.

A mountain of written evidence was ignored too. The Secretary to the Tribunal had been appointed on 6 February 1972 after which he had flown to Northern Ireland. By then the Treasury Solicitor’s Department had begun taking statements from witnesses in London. Meanwhile, the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) had been collecting statements in Derry. All told, 700 would be taken. They were presented to the Treasury Solicitor in London on 3 March and sent to Coleraine the next day.

On 10 March W J Smith, Secretary to the Tribunal drew up a memo which indicates the disdainful and dismissive attitude of Widgery to these statements, all of which contradicted the perjury of the soldiers. Don Mullan published an array of the statements in his 1997 book. It is abundantly clear from it that they were of enormous probative value. Yet, the Smith memo read as follows:

A very large number of these are in fact of no use. It is likely however that had these statements been received at an earlier stage the Treasury Solicitor would have thought it worthwhile to take statements with a view to the writers giving evidence. The LCJ did not see any of the 700 statements until 9 March. Mr Stoker, Mr Hall and myself all discussed the matter with him at different times on that date. I said that if I had been advising a Minister, I would have strongly urged the desirability of taking evidence from at least a few of these potential witnesses, since it was clear that if this was not done there would subsequently be heavy criticism. The LCJ said that he fully understood the point, but did not see how he could avoid such criticism in any case. He considered that the statements, which must surely have been ready for some little time, had been submitted at this late stage to cause him the maximum embarrassment. He was satisfied that there was no real halfway course between not calling any of these witnesses and calling a very large number of them, which he was not prepared to do at this stage. From what he had seen of the statements, only 15 of which Mr Stoker had thought it worthwhile to draw to his attention, he did not think that the people who wrote them could bring any new element to the proceedings of the Tribunal. I enquired whether the LCJ intended to make a public statement about the 700 statements. He said that he did not, but agreed that he should deal with the matter in his report. He was quite prepared to say in the reports that the Tribunal had taken note of all the statements, on the basis that they had all been inspected by Counsel for the Tribunal or by the Treasury Solicitor’s offices. Indeed, in the last resort he was prepared to read them all himself, though Mr Stoker assured him that this was not necessary.

In his report Widgery would say of the statements that they

reached me at an advanced stage in the Inquiry. In so far as they contained new material, not traversing ground already familiar from evidence given before me, I have made use of them.

12. At Best Widgery Misinterpreted the Evidence due to Stupidity, at Worst, he Twisted it to Suit the Cover-up.

All of the soldiers from Support Company of 1 Para, i.e. the soldiers who had killed the civilians in Derry on 30 January 1972, who appeared before Widgery sang from the same hymn sheet claiming the people whose lives they had taken had posed a threat to them.

Widgery reported on 19 April 1972 whereupon it emerged that he had, at best, misinterpreted the evidence, at worst twisted it to suit the cover-up. David Capper, a reporter with the BBC, had told Widgery that he had heard a single shot fired about two hours before the march began. Yet, when the Widgery Report appeared, the judge claimed that:

Mr Capper, a BBC reporter, heard a single revolver shot fired from the crowd he was with at Kells Walk in the direction of soldiers in William Street. He heard this shot after the shooting of Johnson and Donaghy in William Street, but before the Paras moved into Rossville Street.

Capper has criticised Widgery for this misrepresentation. Could the Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales have made such an elementary error or did he twist the evidence to suit the military cover-up?

Widgery’s attention to detail left much to be desired. Daniel Gillespie, who had been wounded, was omitted from that category of victim.

13. Sinner Take All

Insofar as the soldiers were concerned, it was a case of sinner takes all: Widgery professed to believe every word they had tendered to him thus:

Those accustomed to listening to witnesses could not fail to be impressed by the demeanour of the soldiers of 1 Para. They gave their evidence with confidence and without hesitation or prevarication and withstood a rigorous cross-examination without contradicting themselves or each other.

He proceesed to argue that the soldiers who identified armed gunmen had fired on them in accordance with the standing orders in the Yellow Card. He proceeded to say that their training made them aggressive and quick in decision, and some showed more restraint in opening fire than others. At one end of the scale some soldiers had displayed a high degree of responsibility whereas at the other, particularly in Glenfada Park, the firing had bordered on the reckless. These distinctions reflected differences in the character and temperament of the soldiers concerned, he opined.

In truth none of the 14 who were killed were armed; no warnings were given before they were shot; and Soldier F and his colleagues were never in any danger.

14. Deflecting the blame.

Widgery pointed a finger of blame at the NICRA organisers of the march for the tragedy because they had – in his view – created a dangerous situation where a confrontation had become inevitable and that there was no reason to suppose that the soldiers would have opened fire if they had not been fired on first.

Widgery also tried to render a scapegoat out of Brigadier Pat MacLellan, the highest ranking officer in Derry, by opining that the intention of senior British army officers to use the Parachute Regiment as an arrest force was sincere but that MacLellan “may have underestimated” the hazard to civilians in doing this in circumstances in which the troops were liable to come under fire.

The criticism of MacLellan was egregiously unfair. Fot a start, the soldiers did not come under fire (except for a few irrelevant and inconsequential shots discharged by Official IRA men). More importantly, MacLellan had never contemplated sending 1 Para anywhere near the Bogside. Had his will prevailed, the paratroopers might never have crashed through the barriers and Bloody Sunday would not have occurred.

MacLellan, while no pushover, took a largely tolerant, pragmatic and non-confrontational approach to Nationalists in Derry. He believed this tactic would help steady an increasingly unstable set of affairs while the politicians strove for a political solution.

On the other hand, Kitson ran Belfast as if he was a gangster boss with the city his patch. He let his enforcers – the paratroopers – run riot. They were permitted to inflame, provoke, assault and even kill those they believed to have stepped out of line. One mentally challenged girl was snatched from the street by paratroopers and orally raped by a gang of them. No doubt countless sexual assaults were perpetrated by his soldiers. Rifle butts were used to smash teeth, ribs and noses as a matter of routine while Catholic homes were often ransacked. It was Kitson’s paratroopers who perpetrated the Ballymurphy massacre in August 1971. (See: Brigadier Kitson’s motive for murdering unarmed civilians in Ballymurphy.)

1 Para went to Derry on Bloody Sunday on ‘loan’ from Kitson. It was they, not MacLelland’s troops, who perpetrated the massacre. Soldier F was probably the most prolific of the killers that day.

Why Widgery deflected attention away from Kitson – completely – and onto MacLellan is perplexing. Kitson’s name does not even appear once – anywhere – in the Widgery Report. Why?

15. Vilification of the Dead.

While it has long since been established that not a single one of those killed on Bloody Sunday was a gunman, terrorist, nail bomber or troublemaker, Widgery blithely stole their good names, all they had left in this world. According to him, although some of the deceased and wounded were to be acquitted of complicity in wrongdoing, there was a “strong suspicion” that others “had been firing weapons or handling bombs” and that the Support Company troops had returned fire, but only at threats, albeit that some of the shooting had “bordered on the reckless”.

The paraffin test taken of Bernard McGuigan, he alleged, constituted “ground for suspicion that he had been in close proximity to someone who had fired”.

He attacked John Young too saying: “The paraffin test disclosed lead particles on the web, back and palm of the left hand which were consistent with exposure to discharge gases from firearms. The body of Young, together with those of McDaid and Nash, was recovered from the barricade by soldiers of 1 Para and taken to hospital in an APC [armoured personnel carrier]. It was contended at the hearing that the lead particles on Young’s left hand might have been transferred from the hands of the soldiers who carried him or from the interior of the APC itself. Although these possibilities cannot be wholly excluded, the distribution of the particles seem to me to be more consistent with Young having discharged a firearm. When his case is considered in conjunction with those of Nash and McDaid and regard is had to the soldiers’ evidence about civilians firing from the barricade, a very strong suspicion is raised that one or more of Young, Nash and McDaid was using a firearm. No weapon was found but there was sufficient opportunity for this to be removed by others”.

While Michael Kelly was exculpated, Widgery claimed: “The lead particle density on Kelly’s right cuff was above normal and was, I think, consistent with his having been close to someone using a firearm. This lends further support to the view that someone was firing at the soldiers from the barricade, but I do not think that this was Kelly nor am I satisfied that he was throwing a bomb at the time he was shot”.

Kevin McElhinney was vilified thus:

He was shot whilst crawling southwards along the pavement on the west side of Number 1 Block of Rossville flats at a point between the barricade and the entrance to the flats. The bullet entered his buttock so that it is clear that he was shot from behind by a soldier in the area of Kells Walk. Lead particles were detected on the back of the left hand and the quantity of particles in the back of his jacket was significantly above normal, but this may have been due to the fact that the bullet had been damaged. Dr Martin thought the lead test inconclusive on this account. Although McElhinney may have been hit by any of the rounds fired from Kells Walk in the direction of the barricade – e.g., by Soldiers L and M – it seems probable that the firer was Sergeant K. This senior NCO was a qualified marksman whose rifle was fitted with a telescopic sight and he fired only one round in the course of the afternoon. He described two men crawling from the barricade in the direction of the door of the flats and said that the rear man was carrying a rifle. He fired one aimed shot but could not say whether it hit. Sergeant K obviously acted with responsibility and restraint. Though I hesitate to make positive finding against the deceased man, I was much impressed by Sergeant K’s evidence.

With regard to those shot in Glenfada Park, Widgery assassinated them again, this time with innuendo:

It may well be that some of them had been attacking the soldiers in the barricade, a possibility somewhat strengthened by the forensic evidence. The paraffin tests on the hand swabs and clothing of Gerald McKinney and William McKinney were negative. Dr Martin did not regard the result of the tests on Donaghy as positive but Professor Simpson did. The two experts agreed that the results of the tests on Wray were consistent with his having used a firearm. However, the balance of probability suggests that at the time these four men were shot the group of civilians was not acting aggressively and that the shots were fired without justification. I am fortified in this view by the account given by soldier H, who spoke of seeing a rifleman firing from a window of a flat in the south side of Glenfada Park courtyard.

16. Planted Evidence: the Nails Bombs.

Gerard Donaghy was cast as a nail bomber. No one now doubts that nail bombs were planted on him. Yet, according to Widgery:

On the balance of probabilities the bombs were in Donaghy’s pockets throughout. His jacket and trousers were not removed but were merely opened as he lay on his back in the car. It seems likely that these relatively bulky objects would have been noticed when Donaghy’s body was examined; but it is conceivable that they were not and the alternative explanation of a plant is mere speculation. No evidence was offered as to where the bombs might have come from, who might have placed them or why Donaghy should have been singled out for this treatment.

He also held that there had been no general breakdown in discipline, and that for the most part the soldiers had acted as they did because they thought their orders required it. He commented that no order and no training could ensure that a soldier would always act wisely as well as bravely and with initiative, and went on to express the view that the individual soldier ought not to have to bear the burden of deciding whether to open fire in confusion such as those which had unfurled on the day, but that, in the conditions prevailing in Northern Ireland, it was often inescapable.

17. “Bloody Sunday, thanks to the propaganda merchants and half a dozen lazy hacks, was now a closed book, with the Irish fully to blame.”

The majority of people in Britain had found Bloody Sunday little more distracting than a passing parade, albeit a grotesque one. Officially, the report was scheduled for publication on the afternoon of Wednesday, April 19 but the press officers at the Ministry of Defence had other ideas and contacted the defence correspondents of the national newspapers the night before and leaked the sections that showed the army in the best light. ‘Army Can Be Proud’, The Daily Express exclaimed. As Simon Winchester noted:

No mention was made in the “leak” of any “underestimate of the dangers”, of any gunfire that “bordered on the reckless” as Widgery remarked in Conclusion Number 8. Those who read their front pages on Wednesday morning would have had to have been very short-sighted indeed to have missed the results of the PR work. “Widgery Clears Army!’ They shrieked in near unison; and a relieved British public read no more – Bloody Sunday, thanks to the propaganda merchants and half a dozen lazy hacks, was now a closed book, with the Irish fully to blame. [Winchester (1974), p. 210.]

18. Lord Carver’s Praise for a Former Military Colleague, Brigadier Widgery.

Lord Michael Carver, Britain’s highest ranking soldier, knew that Widgery was a former brigadier. Carver felt that the British army had been “fortunate to have, in Lord Widgery, a President of the Tribunal who understood soldiers well and sympathised with them in difficult situations in which they were placed”. [Carver (1989), p. 418]

19. The Worst-case Scenario is that Heath did Not Blackmail Widgery

Widgery was also an active brother of Freemasonry, a secret society notorious for intrigue. There are other even darker possibilities for his misconduct. It has become clear over the decades that Heath was a blackmailer. On his way up the greasy political pole, he served as Tory chief whip, 1956-59. While most Tory whips were blackmailers, Heath brought a professionalism to the task by assembling what became known as the Dirt Book, an encyclopaedia of embarrassing information about his colleagues, designed to stop them stepping out of line. It was exploited during the Suez Crisis. Bearing in mind the crass behaviour of Widgery, it is not unfair to ask if Heath had blackmail material on him which ensured he could control him. In the final analysis, the worst-case scenario is that he had nothing on Widgery and that it was assumed that he would automatically step up to the mark motivated by misplaced patriotism, irrespective of how many had been murdered because he was weak, malleable and/or excessively grateful to the politician for his elevation to the most prestigious legal perch in Britain.

20. Sir James Dunnet, the Sex Criminal at the Ministry of Defence who Helped Widgery

Widgery could not have succeeded in his sham tribunal without the co-operation of the Ministry of Defence at the very highest level. The support was probably provided willingly by Sir James Dunnet, the Permanent Undersecretary (PUS). Had he not wanted to co-operate, he probably would have been blackmailed into so doing by those ultimately behind the cover-up. Dunnet was an abuser of ‘Dilly boys’, young male prostitutes – many of whom were teenagers – whom he picked up at Piccadilly for sex.

Dunnet became involved with Vicky de Lambray, a transvestite male prostitute who stole his cheque book in the early 1980s. De Lambray was put on trial in March 1983 instantly igniting a media frenzy during which Dunnet’s name was made public. De Lambray died in August 1986. Three hours before she/he was found dead, she/he had telephoned the Press Association stating, “I have just been killed. I have been injected with a huge amount of heroin. I am desperate”. She/he claimed that a group of men had administered the injections.

Dunnet and the MoD were undoubtedly also involved in the cover up of the abuse of boys at Kincora Boys’ Home in Belfast while Dunnet was PUS. A number of officers in Lisburn including General Peter Leng, Captain Colin Wallace and Captain Brian Gemmell have confirmed that they knew what was happening at Kincora. Another MoD employee who knew was Peter Broderick.

If all of these MoD officials knew, it is unlikely in the extreme that the upper echelons of the MoD – who employed them – did not know. Hence, it is not unfair to speculate that Dunnet was a party to that sordid cover-up too.

David Burke is the author of ‘Deception & Lies, the Hidden History of the Arms Crisis 1970’ and ‘Kitson’s Irish War, Mastermind of the Dirty War in Ireland’ which examines the role of counter-insurgency dirty tricks in Northern Ireland in the early 1970s. His new book, ‘An Enemy of the Crown, the British Secret Service Campaign against Charles Haughey’, was published on 30 September 2022. These books can be purchased here:

https://www.mercierpress.ie/irish-books/kitson-s-irish-war/

https://www.mercierpress.ie/irish-books/an-enemy-of-the-crown/

https://www.mercierpress.ie/irish-books/deception-and-lies/

OTHER STORIES ABOUT BLOODY SUNDAY, THE BALLYMURPHY MASSACRE, BRIGADIER FRANK KITSON AND COLONEL DEREK WILFORD ON THIS WEBSITE:

Bloody Sunday: Brigadier Frank Kitson and MI5 denounced in Dail Eireann

The covert plan to smash the IRA in Derry on Bloody Sunday by David Burke

Soldier F’s Bloody Sunday secrets. David Cleary knows enough to blackmail the British government.

Colin Wallace: Bloody Sunday, a very personal perspective

A Foul Unfinished Business. The shortcomings of, and plots against, Saville’s Bloody Sunday Inquiry.

Soldier F, the heartless Bloody Sunday killer, is named.

Brigadier Kitson’s motive for murdering unarmed civilians in Ballymurphy.