By Margaret Urwin.

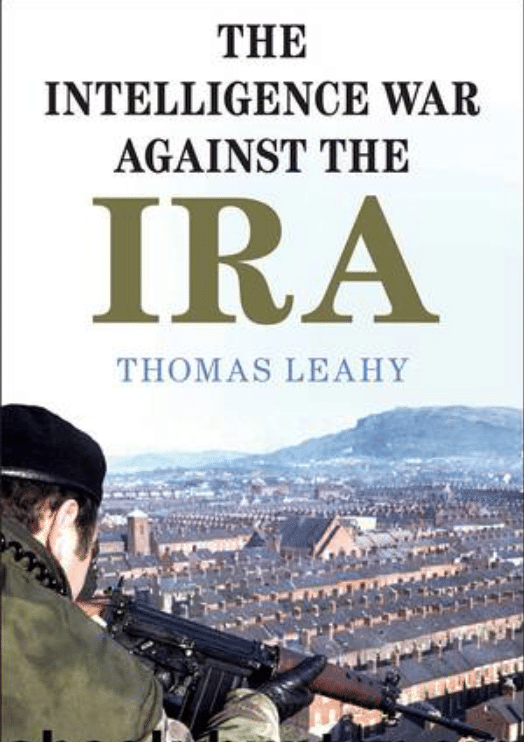

In ‘The Intelligence War against the IRA’, Thomas Leahy, Senior Lecturer in Politics in Cardiff University, challenges the growing dominant narrative that the IRA was brought to the negotiating table in the 1990s because they had been ‘brought to their knees’ by British intelligence.

Since the outing of State agents, Stakeknife and Denis Donaldson in particular, in the early 2000s, many academics, historians and commentators have concluded that the IRA campaign ended in defeat because it was fatally compromised by agents and informers. Existing books and articles, while not studying the intelligence war in any significant detail, yet conclude that British intelligence was vital in forcing the IRA into peace.

Leahy meticulously, painstakingly and, indeed, convincingly, debunks that conclusion.

Leahy meticulously, painstakingly and, indeed, convincingly, debunks that conclusion.

The book is the first to evaluate fully the impact of British intelligence agents, SAS and other operations against the Provisional IRA. From the wealth of material examined in Irish and UK archives, interviews and memoirs, Leahy argues that British intelligence did not force the IRA into surrender and that political factors were crucial in delivering peace. He suggests that, in fact, particular intelligence operations may have, rather, increased IRA support in its heartlands because of anger against the British State.

It is one of the first studies of the conflict that researches what happened by region. It examines British intelligence and security strategy impact on IRA urban units in Belfast and Derry but also rural units in south Armagh, north and mid-Armagh, Fermanagh, south Derry, north Down, south Down and Tyrone. The IRA campaign in England is also considered in detail. Leahy concludes that a previous major focus on the IRA in Belfast has overlooked crucial aspects of the overall picture of what happened and why during the conflict and the regional factors affecting it.

A range of republicans (both pro-peace-process and dissentient) have been interviewed, as well as British security personnel; also memoirs from all sides of the conflict including self-confessed IRA informers and intelligence handlers have been accessed. Of particular value is the extensive use of the relatively new sources of personal papers of Brendan Duddy (intermediary between the IRA and the British at critical times during the course of the conflict), Ruairi Ó Brádaigh and Daithí Ó Conaill, which provide crucial behind-the-scenes insights.

Both British and Irish Government policy towards republicans is reviewed. Leahy suggests that, from 1969 to 1972; 1973-74 and 1976-90, the British State sought to contain IRA violence at ‘an acceptable level’.

Evidence is provided to show that that this policy failed. After the breakdown of the 1975 ceasefire, from 1976, in particular, policies were enacted to marginalise the IRA, e.g., the abolition of ‘Special Category Status’ and the introduction of ‘criminalisation and Ulsterisation’. The intention was ‘to isolate republicans from political settlements whilst eroding the IRA’s armed capacity to a point where they no longer had any influence on Northern Irish politics’. After Roy Mason was appointed as Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, he told Prime Minister Callaghan in January 1977 that there was no intention of engaging in further talks with Sinn Féin and he ended all contact with intermediary Brendan Duddy.

As part of the strategy of marginalising republicans, from my own research I am aware that, also in 1977, the British made vigorous efforts to prove a link between Sinn Féin and the IRA so that Sinn Féin, which had been a legal organisation since May 1974, could be re-proscribed. A lengthy intelligence operation involving surveillance, searches of Sinn Féin offices, seizures of documents and interviews with suspects were carried out for more than a year. However, when the investigation was complete and a report produced in October 1978, the result showed the evidence did not support the view that the IRA and Sinn Féin were inextricably linked and so Sinn Féin could not be re-proscribed.

The book presents original evidence suggesting that republican leaders were seeking talks towards a political settlement in the early 1980s, as Sinn Féin’s electoral mandate was increasing. This was, however, ignored as the British Government tried to negotiate a ‘moderate’ peace settlement with the SDLP and the UUP.

The book presents original evidence suggesting that republican leaders were seeking talks towards a political settlement in the early 1980s, as Sinn Féin’s electoral mandate was increasing. This was, however, ignored as the British Government tried to negotiate a ‘moderate’ peace settlement with the SDLP and the UUP. This initiative failed due to persistent IRA activity, Sinn Féin’s electoral mandate in Northern Ireland and, by 1990, both the Irish Government and the SDLP were anxious to include Sinn Féin in peace talks.

The importance of the rural IRA to the overall campaign is emphasised. South Armagh, in particular, was the strongest unit and, with significant support from the local community, was almost impenetrable. The community had been incensed by the building of watch-towers and constant helicopter flights. Its position of strength enabled it to carry out operations in England in the late 1980s and 1990s.

If the IRA was heavily infiltrated it would not have been possible to carry out a litany of spectacular bombings in England – Brighton (1985); the Royal Marine School of Music (1989); a booby-trap bomb under a car killing Ian Gow MP (1990); the firing of mortars into the back garden of 10 Downing Street (1991); the bombing of the Baltic Exchange (1992) and the NatWest Tower at Bishopsgate (1993); the firing of mortars onto runways at Heathrow Airport (1994) and, after the breakdown of the ceasefire in 1996, the Docklands and Manchester City bombings.

Leahy agrees with Jonathan Powell that talking to all sides involved in the conflict was necessary in order to deliver peace. Sinn Féin’s electoral support was too sizeable to be ignored in a political settlement.

He suggests that, ultimately, it was the political mandate and persistent conflict that led all sides to negotiate and to accept a peace settlement. Nobody ‘won’. It was a political and military stalemate.

The strength and depth of the book in both chronological and geographical terms is impressive. Its thorough examination of the available evidence to date around the British intelligence war in Northern Ireland makes an important contribution to our understanding of the conflict. It punctures the complacent consensus around this topic and should be read with interest by researchers and the general public alike.