Not a week has gone by in 2018 Ireland without several street demonstrations, especially about abortion and the housing crisis. In France, protesting is part of the vernacular. Riots are common: just look at 1789 and 1968. Ireland and France share a reputation for feistiness. A comparison between Irish and French demonstrations could be instructive.

“What do we want? Public housing! When do we want it? Now!”. More than 10,000 people are currently home- less in Ireland. The demonstration I attended, organised by the National Homeless and Housing Coalition, on 7 April was good-natured: festive and serene. People played and sang music as they marched. The Garda seemed engaged and smiled while overseeing the demonstration: a safe protest. It appeared the crowd was representative of the general population, as perhaps you might want. It started at the Garden of Remembrance and ended in front of the Custom House in Dublin in light rain, as cheerful as the weather allowed. Its effectiveness was its mainstream attendance; there was no danger here.

It would, I reflected, be different: more fractious, less representative, angrier – in France.

Ireland fights for Human Rights

At the moment Ireland is in arms over: abortion, education, sex education, health, animal welfare, drugs. But I have the sense that some of these campaigns are not mainstream, even as protests. Certainly the Water Protests were successful, albeit the underlying political message (no new taxes?) and symbolic value were not too clear. Abortion is a long-standing divisive issue in Ireland, symbolising the hegemony and, later, decline of the Catholic Church. Protests date back to 1983 when an unwise blanket prohibition was approved in a referendum. In May there will be a rerun. There are many events, debates and demonstrations on both sides, with pro-choice as fashionable politically as pro-life must have been a generation ago. The demonstration I attended in April was ‘pro-choice’- for ‘Equality, Freedom and Choice’, organised by Rosa. The rally was jubilant and confident, almost over-confident.

The Daddy of all modern Irish marches is the PAYE protests from 1979-1980. Around 700,000 Dubliners marched against the stifling ‘Pay As You Earn’ tax. The BBC called it “the largest peaceful protest in post-war Europe”. But I sense things have changed since then. There is no longer an Ireland the sense that the regime is fundamentally at odds with its electorate. Perhaps it’s because the country now mostly complies with international norms or is fast moving in that direction; perhaps it’s because the country is simply much wealthier and has never been so confident.

In 2003, Irish anti-war protesters organised a demonstration for peace in Iraq. The British and Americans had invaded Iraq. 100,000 walked on the streets of Dublin. It was a thoroughly internationalist protest.

In 2006, a violent demonstration took place in Dublin’s O’Connell Street. For some reason Northern Unionists wanted to organise a ‘Love Ulster’ Parade to honour the victims of the IRA. A counter demonstration materialised and a riot started. Several Molotov cocktails were thrown and cars were burnt. A total amount of 14 persons were wounded and 41 arrested by Garda. Locals put the intense violence down to the alien influence of recalcitrant Northerners: it didn’t symptomise a new riot mentality.

These kinds of demonstrations are pretty rare in Ireland compared to in France, where there are wide-ranging politically-driven strikes and demonstrations every year. Governments can fall as a result of demonstration culture in France.

If France had had an international bailout that was forcibly inflicted on the population; if France had had the iniquities of Nama bailing out the richest failed developers there would have been strikes and riots.

A country’s protest mentality varies from generation to generation.

We’ll put down the Irish monster meetings and boycotts of the nineteenth century as the fruits of a different era. Where a country is colonised and not run for the benefit of the majority – or a significant minority – wideranging subversion is to be expected. In Ireland it culminated in the Easter Rising in 1916 and the War of Independence 1919-21. In the North of course discrimination against Catholics fuelled a later whirlwind. In the Bogside riots of 1969, eight people were killed, a majority Catholic, and over 150 homes destroyed; and the IRA campaign resulted in 1696 deaths. But, though important, this all speaks little to the modern-day Republic of Ireland.

France, protest pioneer

French demonstrations have been well-known and lethal since at least the 18th century with a sustained and celebrated (though not of course by Edmund Burke) historic riot: the French Revolution, facilitating a declaration of the rights of man and changing forever the notion of the political establishment.

In the twenty-first century, protests are still an important political phenomenon. France has been a global leader in dissent.

The rockstar of street opposition was May 1968 when strikes and demonstrations led by students and workers and the occupation of universities and factories across France brought the entire economy of France to its knees and political leaders feared civil war or revolution. The moribund government itself ceased to function for a while after President Charles de Gaulle secretly fled France for a few hours in Germany.

‘68 changed France’s democracy: the super-annuated President De Gaulle resigned, the Assemblée Nationale was dissolved, and government committees were formed to restructure secondary schooling, universities, the film industry, the theatre and the news media.

The Grenelle Accord gave better conditions for the unemployed, a 35% increase in the minimum wage and a fourth week of paid leave for those in employment.

Mentalities started to change too with a sexual revolution from the young. Mixed schools became more common. 1968 sundered a post-War France of austerity, conservatism and asceticism. Nevertheless the movement succeeded “as a social revolution, not as a political one”.

President of the Republic (2007-12) Nicolas Sarkozy famously denounced May 1968 as the source of contemporary France’s problems. The student revolts against bourgeois society introduced a “relativism”, he argued, that undermined national identity, the spirit of honest work, and the institutions of democracy.

Nevertheless it was the gold standard of street politics, it made a difference across society and the economy, and there is no Irish equivalent, at least in the Republic.

After that probably the biggest social movement to coalesce was in 1995 after Jacques Chirac became president in a close May 1995 presidential election. He immediately squared up to the daunting tasks of fixing France’s waning economy, budgetary problems widening social inequality and unemployment rate of 12.3% – higher than that of any other leading industrialised nation.

In his first address to the nation on fiscal policy, Chirac’s prime minister, Alain Juppé, angered the powerful public sector by announcing pay freezes for 1996. He also declared postponements of previously promised tax cuts.

In late 1995, a series of general strikes was organised mostly in the public sector. The strikes were popular despite paralysing the country’s transportation. There were 6 million strike days in 1995, against 1 million the previous year. Among these 6 million strike-days, 4 million were in the public sector (including France Télécom) and 2 million in the private and semi-public sector (including SNCF, RATP, Air France and Air Inter).

Juppé backed down in abject ignominy and was humiliated in elections in 1997. French street protests have traditionally been, and expected to be, effective.

French street protests are also more dangerous. In 2005, two teenagers named Zyed and Bouna were fatally electrocuted after seeking refuge in a power substation. They had tried to escape a police chase as they ran home after a football game to celebrate the end of Ramadan in Clichy-sous-Bois, a poor suburb of Paris . Three days later, a tear-gas grenade was thrown at a mosque by the police. The population had grown sick of police violence. Within a few days, the anger was rife in suburbs across the whole country. Riots caused four fatalities, spreading throughout the Seine-Saint-Denis department, then to all of France at the beginning of November. 56 policemen were injured and almost 3000 people were arrested. Prime minister Dominique de Villepin declared a state of emergency, the first since the Algerian war.

In 2010, a law was enacted changing the age of retirement from around 60 to 62 years of age. Those who want to claim full pension benefits would have to wait until age 67 instead of 65. In 1983, François Mitterrand’s government had reduced the retirement age from 65 to 60.

In 2010 French union leaders initially organised fourteen days of nationwide strikes and demonstrations.

The strikes hit public transport services, lorry drivers blocked autoroutes, and oil deliveries to refineries were disrupted leading to a national fuel shortage. French students joined the workers as barricades were built at around 400 high schools across the country to undermine school attendance. hundreds of thousands hit the streets in 2010. Even the police put the figure at 1.2 million at the height of that protest.

Yet President Nicolas Sarkozy made only minor amendments to the pension proposals. For example some mothers would be able to receive a full pension even if they had taken years out of work to look after children. It was a sign that the public, and political, indulgence of street protests was becoming less wholehearted.

In this context it is helpful to look at the substance of what was in issue. In Ireland the retirement age for people who joined the public service before 1 April 2004 is generally 65. Since 1 January 2013, the minimum retirement age for new entrants is 66 rising to 68 in 2028 in line with the State Contributory Pension. The change attracted little protest, no rioting. The Irish are more pliable.

Demonstrations in France became nastier. At the end of 2015, some Air France’s employees went on strike at Roissy Airport in Paris over a restructuring plan following the Air France-KLM merger which had led to redundancies. A hundred protesters broke down a fence and invaded a boardroom, an Air France HRD and an ex-manager were attacked and had their shirts ripped from their backs. At the moment, twelve people are waiting for a court judgment in the case.

And demonstrations in France have become less rational with less clear goals. For example, in January 2009, a Parisian train station went on strike because a train driver had been mugged a few days before. Around 450,000 people couldn’t use their daily trains. The president of the time, Nicolas Sarkozy eventually demanded an apology from train workers to users of the service: “Public services belong to the public. People are the priority and deserve explanations”.

In February last year ‘Théo L’ was searched by three police officers after becoming violent. According to Théo, one of the policemen had raped him with a telescopic stick. He also said he was the object of racist insults. However, a security camera contradicted these claims showing the police hitting the suspect on the legs and restraining him. In consequence, several riots broke out in Paris and Rouen in solidarity for Théo and against police violence. Windows were broken, cars burnt, teargas fired and hundreds arrested. A police commissioner was convicted of failing to prevent a crime.

In Notre-Dame-des-Landes near Nantes the protest group ZAD, formed in the 1970s, is still protesting against an airport project in a nature reserve. Die-hards refuse to abandon the protest though the project was abandoned last year.

As of 2018 students and lecturers in colleges across France are demonstrating against university reforms proposed by President Emmanuel Macron. Currently, students who pass high-school exams have the right to go to university in their home area. But this has led to popular subjects such as law and psychology being massively oversubscribed and prompted the introduction of an unpopular lottery system where demand is highest.

The lottery system would be scrapped under reforms, with the most in-demand universities allowed to choose students on merit. Even the main student union Fage opposes the students’ blockades and its chief Jimmy Losfeld told French media that some of the student protesters had threatened Fage members.

It is all now coming to a head. Indeed arguably President Emmanuel Macron, with his alleged agenda neither right nor left, has a mandate to bring it to a head, to end the irrational shibboleths of French employment and education. There is absolutely no analogue for this in Ireland.

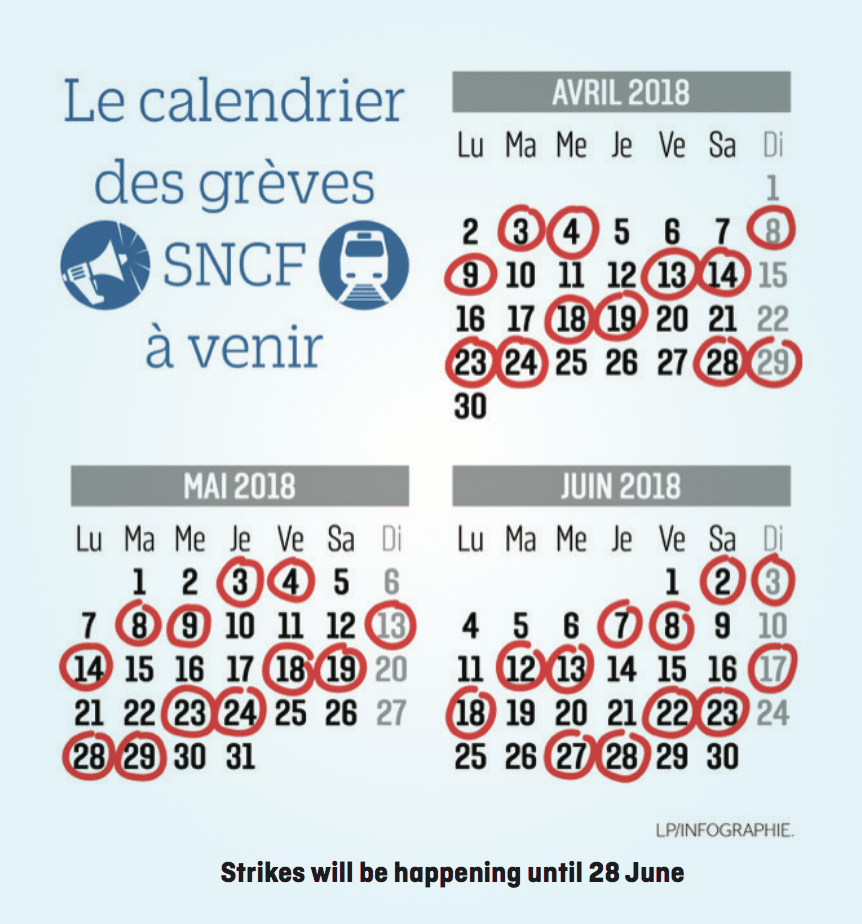

As of April 2018, France’s striking rail unions, led by the powerful communist-led CGT, were facing a test of their popular support after the success of Macron’s bill to reform the country’s debt-ridden state rail operator by changing the legal status of the company to allow competition and the working conditions of new employees. Currently, around 150,000 rail workers in France benefit from a job for life, retirement at the age of 57 (compared to 62 generally) and an array of generous benefits. Among these workers, train drivers are even better treated: they retire at 52 with free life travel or heavily discounted fares for their family. Partly as a result, the impressive state railways have amassed debts of €50bn.

The president is taking his stance based on February’s report by the former head of Air France, Jean-Cyril Spinetta. Under this plan, the French government would help to bail out the SNCF’s debt in return for the reforms. The unions are fighting more than anything to preserve their enviable existing deal; but they are casting the dispute as an attack on unions in general and a defence of state ownership against privatisation (an aim the government has disavowed).

Two weeks into the envisaged three-month strike by the national rail network, SNCF, Macron seemed to be succeeding in convincing the French public that his planned reform was not an act of stealth privatisation but a necessary modernisatikon of an employment status dating back to 1920, when train-driving was simply more demanding.

Macron’s reform bill passed through parliament by 454 votes to 80 and a recent poll showed a majority of the public backed his plans. The railways’ second biggest union is not pursuing action and has criticised the CGT’s strike despite their initially shared antagonism to the biggest railway reform since nationalisation in 1937. The strike on Paris’s metro, buses and trams has floundered: RATP management reported normal service across most of the grid.

And the turnout at protest marches is radically down too. The CGT union said 300,000 people demonstrated across the country, while the interior ministry put the figure at 119,500 and the police claim to have counted just 11,500 marchers in Paris.

Public support for the SNCF protest is weaker than for all but one of several dozen major protests over the last 20 years in France, according to a recent Ifop poll. It showed 42 percent were sympathetic to the strikers.

That compared with much bigger support rates of two-thirds or so for the 1995 strikes. While polls suggest 60 per cent of the French want Mr Macron to pursue his rail shake-up, he has tested the public mood after cutting wealth tax and housing aid and raising pensioner taxes.

Moreover, this confrontation is not just real but emblematic. There has not been a strike-free year on the SNCF since 1959. In 1995, the rail workers were decisive in killing off Jacques Chirac’s welfare reforms, while in 2010 they helped water down Nicolas Sarkozy’s attempt to raise the pension age.

As Village went to press one in three high-speed TGV trains and one in four inter-city services were running as striking workers disrupted services for a seventh day this month.

Demonstrating, but not for the same reasons

It seems Ireland is fighting for civil rights and freedoms against an overhang of conservative law dating from when the country was much more religious. This sense is exemplified by gay rights – until 1993 it was illegal for gay men to have sex, but in 2015 a comprehensive 62:38 approved gay marriage and last year a gay man became Taoiseach. Certainly the Church clings on in schools and some hospitals but it is in catastrophic decline. The reformist spirit is now ingrained and infusing politics. France does not have such a record of recent radical political reform.

This is in part because France achieved so much with its revolution, The country decriminalised homosexuality in 1791, though it remained controversial and clandestine. From 1985 a law prohibited discrimination against same-sex couples. It was only from 2013 that French homosexuals could get married and adopt a child.

Ireland still has major civil rights to vindicate; there is a sense that France, a beacon of revolutionary thinking, has addressed these issues, though of course issues of equality between the sexes and races remain unaddressed. The focus is now on other issues, often workforce rights.

To many it can seem like going on strike or taking to the streets in France is a reflex, an attitude looking for a pretext – even a chance to take a day off work.

Irish and French demonstrations are poles apart. People don’t fight for the same rights or with the same motivation. In Ireland, going on strike nowadays is appropriate and proportionate, a last resort.

The CGT union wants a “convergence of struggles”, where various industrial disputes and causes of discontent come together in a mass upheaval against the reforming government, as happened in May 1968 and more recently at the end of 1995.

The unions are fighting more than anything to preserve their enviable existing deal; but they are casting the dispute as an attack on unions in general and their motivation as defence of state ownership against privatisation (an aim the government has disavowed). Both sides know that French voters cherish their welfare state. However, France’s international reputation as a bulwark of unionisation can be misleading. Only 11% of French workers are in unions, around half the proportion in Ireland or the UK.

Macron has been compared to Margaret Thatcher. Britain’s chaotic recent rail history certainly has lessons for France. Here again, though, the closer one looks, the more distinct the two situations are. According to an editorial in the Guardian newspaper: “Britain’s rail system is a lesson in the dangers of unreformed privatisation. France’s exemplifies the problems of an unreformed nationalised system. The truth is that they both need to change, not to swap identities”.

On the fiftieth anniversary of May 1968 it seems France is adapting the lessons it so determinedly learnt. As to Ireland, it seems it really learnt little from that era anyway.

Marianne Lecach