Real justice requires access to justice, which requires effective access to courts, which requires that courts be accessible without the threat of prohibitive costs. Some 90%, or an even higher percentage, of people in Ireland have no realistic access to justice, due to the prohibitiveness of the costs associated with legal actions via the courts. The Irish system of access to justice is permeated with unfair procedures, unconstitutional laws, and conflicts of interests, which means that most court users in Ireland are vulnerable users.

BalaNCiNG CONFliCTiNG CONSTiTUTiONal RiGHTS:

The English rule (Loser pays rule) on legal costs does not balance two conflicting rights – (1) the property rights of winning litigants, and (2) the right of persons to have access to the courts, without being threatened by unpredictable and prohibitive legal costs.

Notionally, proponents of the English rule claim that winners are entitled to be 100% vindicated, and so be in a position to cover all their legal costs. However, this is a very narrow view, which fails to assess the big-picture consequences: (a) winners are also threatened, up to the point of winning, and can be threatened as defendants, in circumstances where they have no chance of recovery of costs from penny-less plaintiffs. (b) the English rule creates all sorts of conflicts of interests and market distortions, which enormously inflate the costs payable. (c) wealthy litigants can threaten persons of lessor wealth, with adverse costs, such that the case is determined more often by issues of fear, rather than justice. (d) the state, and most government actors become unaccountable, as the decision makers are immune from costs (lumped ontaxpayers, often, with little transparency), but can pursue political goals, or engage in abuse of power, with no financial downside, and can still threaten all challengers with financial ruin; this inequality of arms, means that citizens are generally unable to challenge the unconstitutional laws and conduct of government.

HeNCe, THe eNGliSH RUle iS NOT COMPaTiBle WiTH a Real CONSTiTUTiONal deMOCRaCy:

Costs Allocation Rules incentivise Unfair Adjudication Rules which also incentivise Inefficiencies into the system.

Because the government is allowed to intimidate its challengers with unlimited adverse costs, it then wants to maximise those costs, so as to bolster its threat and avoid oversight; High Legal Costs has been the default weapon of choice for all governments since the commencement of the state; the “Big Stick” is maintained to bounce its opponents out of the ring, and this has so far been achieved with little condemnation by international institutions, which have largely failed to recognise the stealth threat that prohibitive costs represents as a threat to the rule of law.

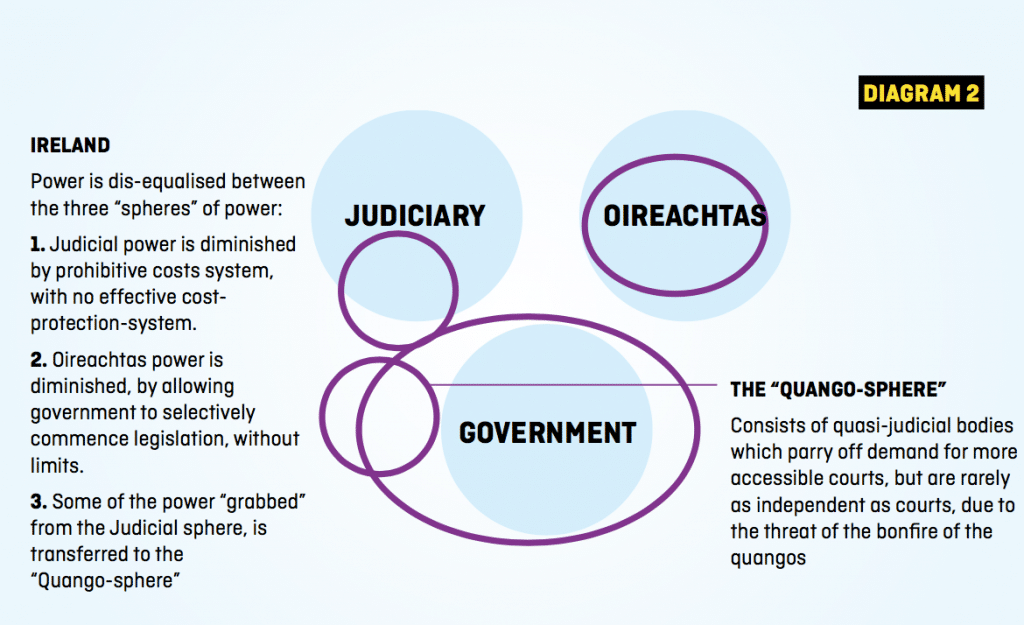

The Big Stick undemocratically deters citizens and/or NGOs from challenging the government when it passes unconstitutional laws, or acts unconstitutionally – this allows the government to pander to its own electoral constituency while depriving less well represented persons access to rights protection, leading to violations of minority rights and individual rights. When populist demands call for adjudicative processes which affect specific rights of connected groups, QUANGOs are often created in order to parry off populist demands for accessible justice. The substitute QUANGO justice can rarely be as independent as courts, and the outcomes are often secretised, thus bypassing democratic oversight.

Hence, the government passes unfair laws for legal costs adjudication, so as to frighten all challengers – this allows it to exercise power with minimum oversight.

THe Need FOR CCOS (COSTS CaPPiNG ORdeRS)

In the ex parte application by Dymphna Maher [2012], the applicant effectively sought an assurance from the High Court that any adverse costs would not be prohibitively expensive, if her lawsuit was subsequently deemed not to have fallen under the ambit of the special costs regime (related to some environmental cases).

Judge Hedigan insisted that there was no legal authority to permit him to make the order sought by the applicant. However, he observed that:

“[It was] very arguable that the absence of some legal provision permitting an applicant to bring such a motion, without exposure to an order for costs, acts in such a way as to nullify the State’s efforts to comply with its obligation to ensure that costs in certain planning matters are not prohibitive. As things stand, I have no power to change this”.

This case along with 12 other cases was appealed to the Supreme Court (SC) on an ex parte basis – where only one of the parties is heard. The SC held that it could not provide such an assurance, on an ex parte basis, as the other side (the EPA) needed to be heard first.

The SC decision in the Coffey case means, in effect, that any person seeing to access the courts in Ireland is threatened with financial ruin, even if just seeking a CCO.

The court failed proportionately to balance the right of access to the courts as a right conflicting with the property rights of government, particularly in the context of the need for real separation of powers. The judicial sphere of power is rendered inaccessible to most citizens, when the loser-pays rule is applied to challenges to executive power, and so the judicial sphere of power is inappropriately diminished; this undermines the checks and balances necessary in a liberal democracy between the legislative, executive an judicial functions.

SePaRaTiON OF POWeRS

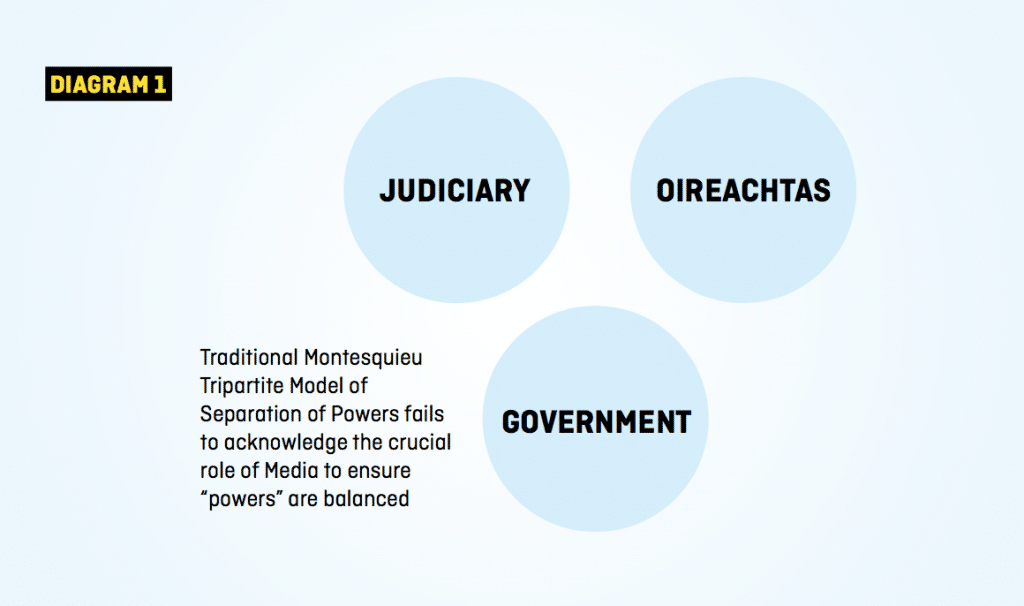

By dividing power between these traditional three spheres, the courts, the government, and the Oireachtas, we help to disperse power and make less probable the accumulation of power to one person, or a small elite, as often happens in what are referred to as illiberal democracies. Diagram 1, above, displays the traditional Montesquieu view of three spheres of power.

However the (Montesquieu) tripartite division of power, is a poor reflection of reality. This is largely because it generally fails to engage with the level of real power held by each of the three spheres, in practice.

A second flaw, is that there should really be five spheres of power, and not three; the people should be seen as the most important sphere, while the media should be viewed as an important sphere also, whose vitality is essential to real democracy.

When populist governments such as those in Hungary and Poland interfere in the independence of the Judiciary, civil society rightly condemns such interferences as rule of law/separation of powers violations. Professor Wojciech Sadurski, writing about Poland in January, said that once illiberal democracies, “begin dismantling separation of powers, constitutional checks and democratic rights, they undermine democracy itself”, although such regimes “want to be liked or even loved, at least by a significant segment of the electorate”.

However, what is less recognised as a separation of powers incursion, is when governments significantly, and disproportionately restrict access to the courts, by maintaining prohibitive legal-costs regimes, amplified by inefficient legal procedures, or less commonly, by restricting the standing of persons who can take constitutional challenges. The judicial sphere of power is significantly diminished, by the maintenance of a prohibitively expensive legal costs system by the legislature. The UK Supreme Court recently recognised that high fees could deter access to justice. It said:

“In order for the courts to perform that role, people must in principle have unimpeded access to them. Without such access, laws are liable to become a dead letter, the work done by Parliament may be rendered nugatory, and the democratic election of Members of Parliament may become a meaningless charade”.

Ireland is particularly challenged by its prohibitive legal costs system, for whose reform there is little political momentum. This stems from a generally held consensus among politicians that it is preferable to maintain a system that reduces opportunities for holding government decisions to account, via the courts. Opposition politicians generally play along and seek to instead gain political kudos for pursuing injustice issues, which in more balanced legal systems would be pursued by the victims, via accessible courts. The lure of relatively unconstrained power when opposition ‘gets its turn’ in power also feeds the continuance of a no- reform agenda.

The inaccessibility of Irish courts to most citizens is probably best exemplified by how few persons seek to use them to pursue civil matters, as evidenced by the fact that Ireland has the fewest judges per capita in Europe, with one sixth of the average per capita number of judges.

Barack Obama in an academic paper on the US criminal justice system, suggested that there should be a “coequal” sharing of power between the three branches of government, so as to ensure that there is real separation of powers. He claimed;

“The Constitution separates the executive, legislative, and judicial powers into three coequal branches of government, all of which have independent roles in shaping the criminal justice system”.

I agree, though what constitutes an equal distribution of power is disputable. However, power parity can only be pursued when the costs of access to the courts are both modest and predictable. This is not the case in Ireland currently, and though courts often refuse to impose adverse costs in cases which involve constitutional challenges, this policy is not predictable, with a requirement being sometimes expressed that a particular challenge must reach a certain threshold of novelty or/and be of exceptional public importance. The positioning of such thresholds is impossible for lawyers to predict in advance, which means that most persons of means are deterred from taking legal actions in Ireland and cannot therefore perform their duties as “guardians of the Constitution”, as referenced by the Supreme Court in the McKenna 2 v AG case (1995). Without willing citizen-guardians, the constitution is reduced to the equivalent of a security hut, without security guards.

The prohibitive level of costs in Ireland coupled with the absence of access to CCOs means that there is a significant imbalance in the real power held by the judicial sphere and the executive sphere as represented by the purple circles in Diagram 2 below; Some of the power “grabbed” by the government is transferred to the “quango-sphere”, which helps parry-off demands for real reform:

In contrast, the South African Constitutional Court has held that in cases against the state or state entities, citizens should be allowed to take cases in constitutional, human-rights or environmental cases, with both the protection of no adverse costs orders should they lose, and with the right to recover costs from the state when they win. In a recent constitutional case, Justice Chris Jafta said that in Biowatch (a 2009 environmental case)‚ the Constitutional Court had laid down a general rule relating to costs in constitutional matters.

“The rule seeks to shield unsuccessful litigants from the obligation of paying costs to the state. The underlying principle is to prevent the chilling effect that adverse costs orders might have on litigants seeking to assert constitutional rights”.

Article 47 of the EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights provides that: “Everyone is entitled to a fair and public hearing within a reasonable time by an independent and impartial tribunal previously established by law. Everyone shall have the possibility of being advised, defended and represented”.

Article 47 overlaps with Article 6(1) of the Council of Europe’s Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), and the ECHR court has signalled a need for costs not to be prohibitive.

Hence, international pressure from the ECJ, the EChr, the UN and the EU Commission may eventually coerce Ireland to provide meaningful access to justice. A failure to do so will a risk damaging Ireland’s reputation as a country that adheres to the rule of law, which could deter international investment.

In this context, and in the context of pursuing the public interest, I submit that a low-cost procedure be statutorily established to allow persons to seek a CCO.

I propose the following procedure:

1. Allow an applicant to apply for an CCO costs protection declaration, initially, on an ex-parte basis via a written submission and/or a hearing if necessary.

2. If a judge determines that there is a reasonable chance that the application, meets a threshold of having a “reasonable chance of success”, then an CCO proposal notice should be then served on the respondent. If the respondent accepts the proposal, then the CCO is established. If the respondent seeks to challenge the proposal, then a hearing is set down for a ruling.

3. Only one lawyer should be allowed to recover costs to represent either the applicant or the respondent at such a hearing. The recoverable costs of such a hearing should be set at a maximum of €1500.00.

4. If a CCO is then established, then a recoverable cost cap should apply to the main hearing of the substantial matter of the dispute relating to a Constitutional/ Human/Environmental) (CHE) rights matter. I suggest that the applicant’s costs liability to the respondent should be set at a maximum of €5,000 for all legal persons.

5. Where the sum of €5,000 is still prohibitive for persons of low income and wealth, then an earmarked fund should be created, to provide legal aid to assist such persons to pay part of the €5,000 contingency. This fund should be administered by an independent agency (such as the Legal Aid Board) on a priority basis – taking account the public interest in the case.

6. The above rules are proposed to apply to all CHE cases, where the defendant/ respondent is the state or a state emanation.

7. The applicant’s recoverable costs (those payable to a prevailing applicant, by the respondent) should be capped at €25,000, with permission being given to the court to increase this level to a maximum of €75,000 in cases which make a significant contribution to the public good. Lawyers should be allowed to engage in any fee arrangements with their clients, subject to fair contract terms. (All sums are inclusive of VAT).

8. Applicants seeking to defend a case on appeal (by respondent) should retain the €5000 cap, as a global cap, but should be entitled to recover up to an additional €5000. Applicants seeking to appeal a negative decision, should be allowed to seek an additional CCO, which should be set by the court at between €1000 and €5000, on top of the original €5000, depending on the public interest nature of the dispute. Allegations that a case is frivolous should only be entertained at CCO hearings, as the threat of retrospective analysis undermines the predictability of any costs protection system.

These proposals are modest, proportionate, fair and do not put any undue burden on the state’s resources.

Kieran Fitzpatrick