By David Burke.

John Hume was the victim of a campaign of character assassination in the early 1970s perpetrated by British spies. It was spearheaded by an individual called Hugh Mooney, a graduate of Trinity College Dublin, who once worked as a sub-editor for the Irish Times. Mooney belonged to the ‘Special Editorial Unit’ (SEU) of the Information Research Department (IRD). It was responsible for the production of black propaganda. Mooney’s boss was the IRD’s Special Operations Adviser, Hans Welser, a veteran of the WW2 Political Warfare Executive. The IRD was part of the Foreign Office and worked closely with the British Secret Service, MI6, which is also attached to the Foreign Office. The IRD operated from a building in London called Riverbank House.

Although Mooney worked at Army HQ Northern Ireland under the cover title of ‘Information Adviser to the GOC’, official documents show that in 1972 he was reporting to the Director and Co-ordinator of Intelligence (DCI) at Stormont – not to the GOC. This means that his activities were known about at a very high level.

Prior to his attack on Hume, Mooney had worked in Bermuda where his colonial and racist side had come to the fore, a story for another day.

Mooney and his associates sought to depict John Hume:

- as part of a communist conspiracy to turn Ireland into Europe’s Cuba;

- as a supporter of the IRA;

- as a fundraiser for the IRA;

- as a thief who stole charitable donations;

- as a man for whom a warrant had been issued for his arrest in 1972.

There may have been other smears which have not yet been detected.

Unintentionally, Her Majesty’s spies and their colleagues in the British Army also made his task of achieving peace extraordinarily difficult at key moments in his career, such as those of Bloody Sunday in January 1972 in his native Derry.

Rogue elements inside MI5 also plotted with the Ulster Workers’ Council (UWC) to tear down the 1974 Power-Sharing Executive of which Hume was minister for commerce. This left Hume without a reliable source of income for a number of years and could have forced him to abandon politics for a job outside of it.

Throughout his career he was placed under surveillance, something that was tantamount to treating him as a subversive. In the 1980s the Gardai in the Republic of Ireland helped MI5 bug some of his conversations. A house where his deputy leader, Seamus Mallon, stayed in 1983 was also bugged by the Gardai.

In the 1990s MI5 opposed his discussions with Gerry Adams.

Hume was a towering political figure of immense courage, foresight and integrity. Boris Johnson has paid him a lavish tribute, praising his “strong sense of social justice” and saying that without him “there would have been no Belfast or Good Friday Agreement”.

Despite Johnson’s fine words, the Tories did their best to stand in Hume’s way during the 1970s, 80s and 90s. In fact it is not an exaggeration to say that they made his life hell.

HEATH IN THE 1970s: Ted Heath served as Tory prime minister, 1970-1974. He sent his black propaganda operatives to Ireland to conduct dirty trick campaigns in the early 1970s. It was they who ran the smear campaign against Hume. Ironically, it is Heath’s legacy which is in now in tatters while Hume’s has never soared higher. Heath’s reputation was destroyed by a report published by the Wiltshire Police in 2017 about his abuse of boys, one as young as 14.

THATCHER IN THE 1980s: Margaret Thatcher, Tory PM, 1979-90, let MI5 (attached to the Home Office) spy on Hume in gross violation of his human rights. Some of this surveillance was carried out in the Burlington Hotel in the Republic of Ireland with the assistance of the Republic’s special branch.

The first steps of the peace process were taken in the middle of Thatcher’s premiership in 1986 when a back channel was opened between Gerry Adams and Charles Haughey via Fr. Alex Reid. Haughey ‘s Northern Ireland adviser Martin Mansergh was a pivotal figure in the process. Thatcher’s battery of spies do not appear to have had any inkling of what was afoot. Had Thatcher discovered this development, it is – to put it mildly – likely she would have denounced it. The Haughey-Adams process was so secret that even John Hume did not know about it when he entered the process later and expressed disbelief when he finally discovered this fact.

MAJOR IN THE 1990s: Thatcher’s successor at 10 Downing Street, John Major, PM 1990-97, was not supportive of the next phase of the process which became known as ‘Hume-Adams’. In 1993 and 1994 key elements of the press in the Republic denounced Hume’s dialogue with Adams, in particular Conor Cruise O’Brien who wrote for Ireland’s Sunday Independent. O’Brien was close to a number of dubious intelligence figures such as Dame Daphne Park, a self-confessed MI6 dirty tricks expert and David Astor, one of MI6’s most important assets in the media. O’Brien knew them through the British-Irish Association (BIA) which Astor had helped set up in the 1970s, and which Park co-chaired in the 1980s. It was Astor who appointed O’Brien as editor of The Observer.

Haughey considered the BIA a British Intelligence front and forbade Fianna Fail figures (such as Brian Lenihan) from attending it. How much O’Brien was influenced by his friends in the British Establishment is an imponderable.

Major, who had an exceptionally close relationship with his spymasters, was not supportive of what Hume, Adams and Dublin were trying to achieve either. Eventually, Bill Clinton had to intervene to twist Major’s arm and move the process forward. Still, MI5 tried to derail it. Haughey’s successor as taoiseach, Albert Reynolds, 1992-94, became so concerned about the hostility of MI5 that he told Major to ignore what MI5 was telling him and that he – Reynolds – would keep him straight about what was really happening in Ireland. Meanwhile, Hume withstood the media hostility and maintained his contact with Adams. The full story of MI5’s interference in these affairs has yet to emerge.

UPDATE 27 Decenber 2020: For an update on the John Major era see UK memo on John Hume’s ‘private life’ is declassified revealing the interest of PM John Major’s top civil servants in ‘possible press stories regarding John Hume’s private life’.

Why did the Tories, the Foreign Office, the Home Office and Her Majesty’s spies distrust, oppose, spy upon and vilify Hume throughout his career? Why did certain Gardai (Irish police officers in the Republic) help them spy upon him?

The trouble began in the early 1970s when Hume began to make trips to Washington where he forged excellent relations with Tip O’Neill, Ted Kennedy and other influential Irish-Americans.

Seán Donlon, who was Irish Consul General in Boston from 1969–71, is quoted in the book ‘John Hume in America’ as saying:

“John began to form the view that organised as it was, Irish-America was not the route to power. Organized Irish-America was extraordinary in the sense that there were maybe 500 different groupings – whether it was the Donegal men, Cork men, the Éire Society of Boston, the Irish Cultural Centre – you had lots and lots of organisations dealing with specific issues, for example, immigration or dealing with social matters. But John quickly came to the view, and he was absolutely right, that these are not the route to power; these people are not into the American political scene. If I want to influence American policy somehow or other, I’m going to have to break into the Washington scene … I think very quickly John began to focus on: Where is the power? Who has the power? How can I enter that zone of power? [See Maurice Fitzpatrick, ‘John Hume in America: From Derry to DC.]

The former Irish diplomat Michael Lillis has pointed out that the US President, the Secretary of State and the State Department were the:

“three offices of the United States, which actually make up the foreign policy of America”.

Yet they were:

“completely controlled by the British. The British had enormous influence in Washington, more than any other country in the world”. (See John Hume in America.)

And according to Hume’s biographer, Barry White:

“The British watched from a distance, wary that he might try to prise the US State Department away from its pro-London, anti-interventionist line. Indeed, it was partly to break the State Department’s hold on policy that Hume concentrated on the politicians, who in America wield real power”.

And Hume was indeed set on nothing less than breaking Britain’s hold over the America’s policy towards Ireland. Maurice Fitzpatrick sums it up in his book thus:

“From 1922 onwards, the ‘Special Relationship’ kept the agents of Irish nationalism shut out of American politics. Despite timid initiatives, nothing emerged and nothing took America off the fence. It was clear to the British government that it could run the North without external interference. For John Hume, it was clear that the British retention of a monopoly on Washington meant that their interests and their perspective on Northern Ireland would continue to be furthered, to the detriment of a fair solution. Somehow, a channel needed to be created to access the White House (which had been markedly unused during the JFK presidency), to break the indifference in Washington towards Ireland, an intransigence which was replicated in British policy towards the Northern minority.”

Adding insult to this injury, in 1971 Hume had helped smuggle details about the maltreatment of internees out to the Sunday Times, causing an international uproar.

By August 1972 the IRD and MI6 was ready to strike.

Some of Hume’s US visits were as Chairman of the Northern Ireland Resurgence Fund (NIRF), a charity which raised funds to encourage employment and self-help projects in Belfast. One of its early initiatives had been to raise money to re-build Bombay Street, which rampaging Loyalist mobs had torched in 1969.

The IRD and MI6 now claimed some of the money raised by the NIRF had been diverted to the IRA while Hume had carved off a slice for himself.

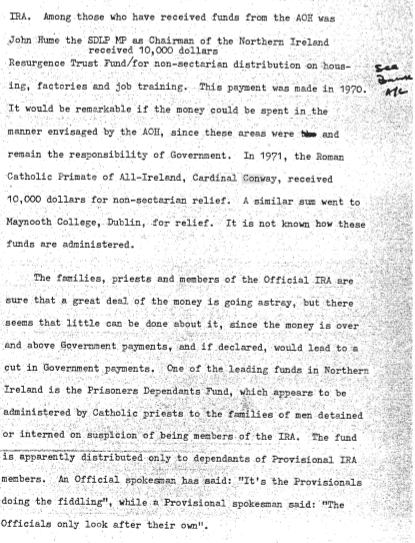

The IRD forged a bank account purporting to show theft from various US charities. The IRD showed a briefing paper to a select group of American reporters. It (a) linked Hume with IRA fundraisers, and (b) hinted that he had stolen money which had been donated by the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH) in America. According to it, Hume “received 10,000 dollars”. Scribbled alongside this in red ink was “see bank a/c”. A black and white copy of the relevant extract from the briefing paper appears in the picture below. Mooney’s handwritten note is circled by us in red.

The smear oozed its way into the Christian Science Monitor, an international publication which, while it was available on subscription, was also distributed free to influential political figures throughout the world. The story festered and spread until Hume was obliged to denounce it.

In April 1987 Barry Penrose of the Sunday Times confronted Mooney with the briefing paper. At first, he denied he had written the briefing or had seen the forged bank account. Later, he conceded the handwriting on the briefing “could be” his. Clearly, he had seen the forged bank account too. How could he have penned a note on the margin of the briefing paper about a bank account if he had not seen it?

It is likely that the briefing paper and the fraudulent bank account statement were shown to Irish-American politicians by British diplomats in Washington in 1972. The British ambassador at the time had a background in banking, Lieutenant-Colonel George Rowland Stanley Baring, 3rd Earl of Cromer.

The British Ambassador to Ireland at the time was Sir John Peck. He had run the IRD in the 1950s.

Anthony Cavendish, who worked for MI5 and later MI6, produced a controversial book, ‘Inside Intelligence’, which the British Government tried to ban. It finally emerged in 1990. In it Cavendish described how MI6 used blackmail to control MI6 agents and also ‘threats to the family of valuable informants”. He described how:

An operative member of MI6 cannot automatically rule out such methods of achieving the required result in an intelligence mission. Similarly, theft, deception, lies, mutilation and even murder are considered if and when necessary.

Cavendish’s revelations provide an insight into the type of people who worked for MI6 and were responsible for the vilification of Hume. Cavendish was a close friend of Sir Maurice Oldfield of MI6, the man behind all ‘black’ operations in Ireland at the time. He was the then Deputy Chief of MI6. He would serve as Chief, 1973-78. He was a ruthless individual. According to Cavendish, Oldfield once sent a poisonous tablet to an agent so he could commit suicide rather than disclose MI6 secrets under interrogation. Oldfield was undoubtedly the overarching mastermind behind the campaign against Hume.

At the time of the smear, Oldfield was running the Littlejohn operation during which he sent two convicted British criminals to Ireland to assassinate IRA leaders, rob banks and attack Garda stations, all to panic Des O’Malley and Fianna Fail into enacting more stringent anti-IRA legislation. The Littlejohns masqueraded as IRA members but the Gardai knew full well (and have admitted privately) that they knew they were British agent provocateurs.

If Britain was behind the December 1972 Dublin bombings which saw two fatalities – as it almost certainly was – the blood of those victims was on Oldfield’s hands. Taoiseach Jack Lynch stated publicly in 1973 that he was suspicious that British agents had perpetrated it. Years later it emerged that Albert Ginger Baker, a British agent inside the UDA code named ‘Broccoli’ by his handlers, had helped transport the explosives used in the attack. Baker is still alive.

One of Oldfield’s field operatives, John Wyman, was caught in December 1972 in Dublin and spent six months in prison.

Thatcher took Oldfield out of retirement and sent him to Northern Ireland in 1979 to co-ordinate all intelligence efforts on the island. His tenure was cut short after his sexual fondness for sleeping with young males was discovered. This led to the discovery of a collection of pornography featuring young males in his flat at Marsham Court in London. MI5 then carried out an inquiry to see if he had been blackmailed by the Russians. In 2016 MI6 informed the Hart Inquiry that Oldfield was a friend and had had a ‘relationship’ (presumably professional) with the man who ran Kincora Boys’ Home in Belfast, the epicentre of an infamous paedophile scandal. See also: Maurice The Mole? The Provisional IRA knew Sir Maurice Oldfield, Chief of MI6, was a homosexual. Did the Soviets know too?#

The British government, the Foreign Office and MI6 were actually making a grievous mistake in attacking Hume as he was set on a course which would pull influential Irish-American politicians away from the Provisional IRA. As Seán Donlon has explained:

“The American media could easily relate to what was happening in Northern Ireland, particularly in 1968–69 because it was almost a copy of the Civil Rights Movement in their own country. The complexities were not easily understood in the United States; people understood civil rights, housing, electoral reform, discrimination, all of these things were understood. What was not easily understood was: Where was Northern Ireland? Why was it a part of the United Kingdom? What was the background? Why did people want a United Ireland, and of course in the Irish-American community, why don’t we achieve it by violence? In 1969, even people who subsequently became phenomenal supporters [of Hume] – Tip O’Neill, Ted Kennedy, and Hugh Carey – were inclined to look towards what became the Provisional IRA. That was their first instinct.” [See Maurice Fitzpatrick, ‘John Hume in America: From Derry to DC.]

Hume was also smeared by MI6 and the IRD in a book published by an IRD operative called Brian Crozier in 1972. In his memoirs, Crozier described his close friendship with Oldfield and his role as an IRD propagandist. His Irish smear volume was entitled ‘Ulster Debate’. An entry in the chronology section for 16 February 1972 contains a reference to an arrest warrant issued for Hume. The entry did not describe the crime (which of course was non-existent) which had prompted the warrant. It merely stated that:

[a] “summons was served on Mr. John Hume in the Bogside, by police escorted by armoured cars”.

‘Ulster Debate’ sold well in Ireland and Britain and contained an article by Garret FitzGerald which afforded it great credibility.

A more extensive account of Mooney and Crozier’s smear operations can be found at Licence to deceive.

Mooney and the IRD had another swipe at Hume by attempting to portray the civil rights movement of which he was a leading light as a violent communist conspiracy.

Mooney generated press briefings which were shown and/or given to journalists. A two-page document is reproduced in full at the end of this story. Unfortunately, it is somewhat difficult – but not impossible – to read. It was written by the IRD and disseminated by Mooney to select journalists. It was also shown to politicians by British diplomats in places such as Washington. It links the civil rights movement to the Soviet Union and the IRA as part of a Soviet conspiracy. According to it, the civil rights movement was part of a:

“murder and sabotage plan, fronted by the IRA, which basically seeks to create in Ireland a socialist republic on Cuban lines. This achieved, the next step would be the drive for a British Workers’ republic”.

The “Civil Rights movement” is described as being “IRA and Communist controlled”.

Mooney also claimed that:

“Communist involvement in Irish political violence has been slow to reach the firm control it now exercises, but it was always there…. Soon it was staging militant demonstrations, using the front of demands for civil rights, and when the demonstrations led to street disorders the IRA came into the picture as escort for their parades.”

The overall picture depicted by Mooney was that:

“militant students, the civil rights bodies, the IRA, and the various Citizens Defence Committees which came into existence in Catholic areas, all had the same objective. In the words of one of their leaders ‘We don’t want reform of Northern Ireland-we want a revolution in Ireland”.

Mooney also smeared British Labour MPs, union officials and other left-wing groups.

Insofar as Ireland was concerned, his main strategy was to demonstrate that the conflict in the North was Communist inspired. Village has seen some of the annotations he made on the front of a Sinn Fein Ard Fheis document linking Sinn Fein to the British Labour Party.

The IRD also forged a Bloody Sunday commemoration leaflet designed to show that certain British Labour politicians were ‘sympathetic with the IRA’.

Edward Short was Deputy Leader of the Labour Party. A similar attack to that on Hume was launched against him, namely the forgery of a bank account showing the receipt of dubious funds.

He also attacked Cardinal Conway in his John Hume finance document. This was probably done because MI6 and the IRD believed the Cardinal had failed to deal effectively with a priest who had allegedly been involved in the bombing of Claudy.

The IRD also attempted to destabilise Ian Paisley, inter-alia, as the policy of the Tory Party was to support the Official Unionist Party.

In 1973, the Foreign Office was in the process of reducing the role of the IRD. Mooney and his colleagues saw the conflict in Norther Ireland and the industrial unrest in the UK as an opportunity to avoid those cutbacks. His document, ‘Soviets gain control over British Communists’, was an attack on the British Labour Party led by Harold Wilson in the run up to the General Elections in 1974. In IRD’s view the Miners’ Strike and the ‘Three Day Week’ crisis was Communist inspired.

The IRD also attacked Fianna Fail politicians in the Republic including Charles Haughey.

There were others sources of serious conflict which set Hume at odds with Ted Heath’s government. Tensions betweeen Nationalist and the British reached a boiling point in January 1972 when a civil rights anti-internment protest ended in the Bloody Sunday massacre in Hume’s native Derry. It proved to be a decisive turning point in the Troubles because it drove Nationalists into the arms of the both the Official and Provisional IRA.

While Hume was fighting for justice for the victims of Bloody Sunday, Mooney was pumping out lies which portrayed the innocent victims of the murders perpetrated that day by the Parachute Regiment as gunmen.

During the uproar over what had happened, Mooney reached out to the writer T. E. Utley for help. Utley was what was known in the intelligence community as an ‘agent of influence’. According to a letter Mooney wrote to his superiors, Utley agreed to help smear the Bloody Sunday victims. According to a letter dated 18 August 1982 by T. G. Baker of the Foreign Office, Utley and Mooney had formulated a plan and Utley was “obviously” going to “need a certain amount of help from Army PR, particularly on the propaganda aspect”. The plan was for Utley to produce a book. In the event, it never materialised. However, in 1975 Utley published the rather grandiosely titled ‘Lessons of Ulster’ which took a broader look at NI and contained a few pages which addressed Bloody Sunday. His overall thesis was that the British Army had been the real victim of the event because they had fallen for a trap sprung for them by the IRA.

According to Utley, the IRA lured the paratroopers from behind their barricades to arrest the rioters and then fired on them in the expectation they would make mistakes under pressure. In reality, the IRA had agreed to keep away from the march and the soldiers fired indiscriminately and without provocation at unarmed civilians. Utley’s fantasy account described how “the Army proved to have walked straight into an IRA trap…The most familiar of terrorist techniques – the use of an apparently innocent protest demonstration as a shield for a gun attack on security forces, designed not primarily to injure them but to tempt them to action which could be misrepresented as the deliberate slaughter of the innocent – had worked to perfection”.

The most outrageous part of his tract was where he argued that some of those killed were “fresh-faced boys who might otherwise have lived to swell the ranks of patriotic militancy” i.e. they were all potential Provos and probably deserved what they got.

The damage occasioned by the snake oil Utley fed his credulous readers should not be under-estimated: Margaret Thatcher would later describe him as “the most distinguished Tory thinker of our time”.

The events of Bloody Sunday made John Hume’s attempts to divert Nationalists away from the path of violence extraordinarily difficult. Nonetheless, he did not buckle. Instead, he became a key figure in securing the Sunningdale Agreement which led to the establishment of a Nationalist-Unionist Power Sharing Executive in 1974. Hume became its Minister for Commerce.

Yet again, the dirty tricksters intervened. Rogue MI5 officers conspired with the anti-Executive Ulster Workers Council (UWC) campaigners who launched a strike to paralyse Northern Ireland and thereby pull down the Executive.

Barry Penrose of The Sunday Times interviewed an acknowledged MI5 agent, James Miller, who told him:

‘I did a dangerous job over there for nearly five years and many UDA and IRA men went to prison as a result,’ [Miller] said last night. ‘But I could never understand why my case officers, Lt Col Brian X and George X, wanted the UDA to start a [Loyalist] strike [against the Northern Ireland Power-Sharing Executive] in the first place. But they specifically said I should get UDA men at grass-roots level to ‘start pushing’ for a strike. So I did. ‘

[Miller] said his MI5 case officers told him Harold Wilson was a suspected Soviet agent and steps were being taken to force him out of Downing Street. [Miller] said that in early 1974 his case officers instructed him to promote the idea within the UDA of mounting a general strike which would paralyse Northern Ireland. The result, says [Miller], was the Ulster Workers’ Strike in May 1974 which severely embarrassed Wilson’s government and helped to torpedo the Sunningdale Power Sharing Executive of Catholics and Protestants, which had included an ‘Irish dimension’ by allowing the Irish government a consultative role in Ulster.

Miller’s status as an MI5 agent was confirmed at the Saville Inquiry into Bloody Sunday and also at the Hart Inquiry into historical child sex abuse in Northern Ireland.

Hume’s biographer Barry White described how Hume believed there were ‘indications that the UWC had early warnings of security decisions’. White described how the UWC’s:

main source of information was through a former senior civil servant who retained good contacts at Stormont, and there was a valuable reassurance in an anonymous telephone call midway through the strike. A man with a cultured voice, who seemed to know what was happening inside Stormont, simply told [strike leader Andy] Tyrie to “keep up the good work” and victory was certain.( p. 167)

During the strike, Hume clashed with the top intelligence figure at the NIO, Denis Payne of MI5. Hume sat in on a meeting at which Payne was also in attendance. At it, Hume challenged the assertion that the NI Electricity Service had been reduced to a paltry 30% output due to the strike. Shortly after this he secured a meeting with the NI Secretary, Merlyn Rees, to challenge the claim. Payne joined this meeting to confirm the 30% output position which showed that the strike was succeeding. This pessimism weakened the resolve of those supporting the doomed Executive.

The Executive was on its last legs when Loyalists bombed Dublin and Monaghan killing 33 people and a full-term unborn child. The perpetrators of the atrocities have since been confirmed as RUC special branch agents which means they were ultimately controlled by Payne and MI5. Another senior MI5 figure, Ian Cameron, was deeply involved in the control of MI5’s assets inside the UDA. MI5 either let them go ahead with the attacks or directed them from the outset. Either way, they were complicit. The bombs helped speed up the collapse of the Executive. The Irish government has tried in vain for decades to get the British government to hand over its files on these attacks. Tony Blair and others have steadfastly refused.

A few years after the collapse of the Executive, the Republic’s EEC Commissioner Richard Burke, 1977-81, asked Hume to become part of his Brussels cabinet, a position which not only enabled Hume to continue his public life but also forge multiple contacts with European governments and paved the way for his later success as an MEP in Europe. All of this deepened Hume’s capacity to harness the support of Europe towards the goal of achieving a lasting peace in Ireland. The Foreign Office, MI5, MI6 and the Tories must have been dismayed as they watched Hume’s progress in Europe.

By the 1980s MI5 was acting in concert with certain Garda officers to spy on Hume during his visits to the Burlington hotel in Republic. By now MI5 (attached to the Home Office) had assumed the dominant role over intelligence operations in Ireland, including those in the Republic. There was a large amount of perfectly legitimate co-operation between MI5 and the Gardai but the surveillance of the Leader of the SDLP could not conceivably have come under that heading. Clearly, this was political espionage; in other words, treachery.

Larry Wren was Garda Commissioner, 1983-87. He had served as the Head of Garda Intelligence, C3, in the 1970s when he had forged excellent relations with MI5, especially with a man called Michael McCaul. As commissioner, Wren maintained a firm grip over all intelligence operations run by the Special Branch. It was special branch officers who monitored Hume’s hotel room at the Burlington hotel in Dublin.

The gardai are only allowed to place criminals, subversives and foreign spies under surveillance. Suffice it to say, the surveillance of Hume was illegal. It is not clear what the officers in the field knew about where the recordings were going. They may simply have been acting on orders from above. Whoever handed them over to MI5, however, was guilty of treachery to the Irish State.

For the avoidance of any confusion: the Irish government did not order, know about or receive the transcripts of the Garda recordings of Hume’s conversations at the Burlington hotel.

Why is it clear the recordings went to MI5?

Garret FitzGerald was Taoiseach at the time. John Hume told him about it.

Hume had discovered what was afoot after a discussion with an MI5 officer posing as a civil servant at the Northern Ireland Office (NIO). FitzGerald later approached the British government – at Hume’s request – to get them to desist in their surveillance of him.

Fitzgerald did not haul Wren over the coals, nor see to it that the Garda Special Branch officers who had monitored the Burlington Hotel were interviewed to establish whether they knew the reports were being sent to MI5.

The Garda unit behind the surveillance had gained access to the phone exchange in the basement of the Burlington where they had attached a recording device to the line which went to the room Hume was using. The handpiece in the room acted as a microphone which picked up what was being discussed in it. The officers involved waltzed in and out of the hotel at will masquerading as technicians and took tapes away and replaced them with fresh ones.

The Burlington hotel scandal was kept under wraps but an indication of the uproar that might have erupted was demonstrated by another scandal involving the surveillance of a senior SDLP MP in Dublin at roughly the same time as the surveillance of Hume.

Hume’s Deputy Leader, Seamus Mallon, was placed under surveillance by the same Garda unit while he was staying at home of the Moyna family in Kilbarrack, Co. Dublin during the New Ireland Forum in 1983. While Mallon was not the target – or at least not the primary one – a bug placed in the kitchen of the house was perfectly capable of picking up his conversations. In the event, the bug was discovered shortly after it had been installed.

Two senior former gardai have confirmed to Village that the men who bugged the home of the Moynas were gardai. One laughed out loud at the mere suggestion that there was any doubt about this.

The officers involved in the bugging drove a yellow van painted to make it look like it was an official Post & Telegraphs service vehicle. After the bug was discovered, Wren not only covered up for the surveillance unit but masterminded the attempt to frame two Republicans for the intrusion. That attempt failed when the two men were found not guilty. They were Patrick Stagg of Palmerstown and John O’Doherty of the North Circular Road. Stagg had served a five-year sentence in Portlaoise Prison after a conviction for possession of explosives. He chose to serve his sentence in the Provisional IRA section of the prison but was a member of the INLA. O’Doherty was a former member of the Official IRA from Swatragh, Co Derry. He left it after the 1972 ceasefire. He became a founding member of the Irish Republican Socialist Party, the political wing of the INLA and an active member of the INLA.

It is inconceivable that Garret FitzGerald did not realise what had taken place at Kilbarrack, especially in light of what Hume told him about the bugging of his hotel in Dublin.

FitzGerald produced two biographies and tens of thousands of words for his newspaper articles. Whilst he wrote about virtually every aspect of his career, especially Northern Ireland, he never broached the Burlington hotel bugging.

Overall, FitzGerald’s behaviour during the Moyna bugging scandal was – to put it mildly – perplexing. Seamus Mallon was furious at him for his inaction. The scandal finally erupted long after FitzGerald had been told about it, yet had done nothing more than ignore it.

The 1983 bugging eventually became public knowledge in 1984 when Vincent Browne exposed it on the front page of The Sunday Tribune. The paper continued to report on it for months with Browne and Paddy Prendiville to the fore. Phoenix magazine followed up with a series of detailed reports about the Garda unit written by Frank Doherty. Fianna Fail demanded a judicial inquiry.

The Irish public would not have tolerated the illegal surveillance of both the leader and deputy leader of the SDLP by the Irish police and the attempt to frame two men for one of the operations. Assuming FitzGerald was not taken in by the lies and deception that swirled around the Burlington and Moyna affairs, it is fair to speculate that he covered-up for Wren and the gardai because the scandal could have destroyed faith in the gardai, disrupted legitimate Garda-MI5 co-operation and damaged Anglo-Irish relations.

There is no doubt that MI5 would also have had Hume’s phone in Derry tapped and they would have spied on him generally throughout his career. MI5, which is attached to the Home Office, would have monitored him in Ireland and Britain. MI6, which is attached to the Foreign Office, would have taken up the task when he went to Europe, the US and elsewhere. Technically, the interception of his communications would have been undertaken by the eavesdroppers at GCHQ.

The stress on Hume from all of this must have been unbearable at times.

Alan English is the new editor of the Sunday Independent. On 9 August, 2020, he made a dramatic break with the past. The paper had been vocal and vitriolic in its opposition to Hume after it became public knowledge that he was talking to Gerry Adams. English confronted the thorny issue of the paper’s coverage of Hume in 1993 and 1994 head on. He had been living in England at the time of the campaign against Hume. Writing on 9 August 2020 he stated that:

“It was a different Ireland in 1993 – and a different Sunday Independent. .. I was living in London at the time and have little memory of that coverage, but over three days last week, I trawled through the Sunday Independent archive and read everything published on the Hume-Adams talks in 1993, when the analysis was at its most trenchant… Week after week, Hume’s initiative was on the receiving end of intense scrutiny – as the newspaper would have described it at the time. Others thought differently, describing what was published as poisonous – “persistent and vicious attacks”, as one friend of Hume’s put it. … The man described by Bill Clinton as “Ireland’s Martin Luther King” was accused of being behind “a shabby charade in the name of peace”. It was speculated that his decision to sit down with Adams would prove to be “a miscalculation of historic proportions”. … It was this weekend 27 years ago – August 8, 1993 – when suspicion bordering on hostility gave way to what can be fairly described as an all-out attack on Hume mounted by the paper’s biggest star writer of the day.”

Elsewhere in the Sunday Independent, Michael Lillis, a former senior civil servant who knew John Hume, wrote that:

“The vitriol gushed Sunday after Sunday and I know that it caused him immense distress. He suffered a public emotional breakdown at the funeral of eight victims of the UDA in Greysteel on October 30, 1993.“

Sean Donlon, a senior Irish diplomat, was quoted as having written that:

“the Sunday Independent’s persistent and vicious attacks on John Hume were a serious mistake, an absolute disgrace and damaged the reputation of Irish journalism”.

Sir Anthony O’Reilly owned the Sunday Independent – and other papers – at the time of the onslaught on Hume. O’Reilly exercised great control over them and his editors. A concrete example of this was revealed by Michael Daly, the Head of Chancery at the British Embassy, 1973-76. Daly’s ostensible responsibility was for “information”. In 1975 he transmitted a cable to London which revealed that O’Reilly had:

“instructed his editors at lunch that no support whatsoever was to be given to Haughey’s efforts to return to respectability [after his acquittal at the Arms Trial].”

Daly later went to serve in Nicaragua (during the Contra era), Chad, Costa Rica and Bolivia, and was probably an MI6 officer. Indeed, the Head of Chancery, was the traditional cover for the MI6 Head of Station in Dublin.

Bearing this tight control in mind, it is fair to ask what role – if any – O’Reilly played in the coverage of the Hume-Adams discussions in 1993/94. The editor of the Sunday Independent at the time of the assault on Hume was Aengus Fanning who has since died. Sir Anthony is still alive yet did not contribute to the extensive analysis of the Sunday Independent‘s coverage of its 1993/94 output which was published on 9 August 2020. It would be fascinating to hear his side of the story. In particular,

- was he urged to oppose the Dublin-Hume-Sinn Fein/IRA talks by his friends in the British Establishment of whom he had many?

- what discussions did he have with Fanning about the coverage?

- what did O’Reilly think of the comment by one journalist that: “Mr John Hume, being the principal international enforcer, licensed to speak to the world on our behalf, the political bomber flying over unionist heads trying to kill them. Hume has stated with commendable clarity, which for him is unusual, that if Britain and the unionists don’t do business with him, they will have to deal with the IRA, with physical rather than political force.”

Aengus Fanning once said that:

“One of the strengths [of the paper] at the time was the support of the proprietor, Tony O’Reilly, who was absolutely steadfast when all sorts of efforts were being made – on both sides of the Atlantic and Irish Sea – for him to intervene and change things. He was absolutely rock solid. And that was not an easy thing for a man in his position.”

What pressure was being placed on O’Reilly?

Who was exerting it?

Why did figures in London and Washington believe they might be able to get O’Reilly to do their bidding?

Fanning’s quote about O’Reilly resisting pressure being made from “both sides of the Atlantic and Irish Sea” to “intervene and change things” was quoted in the Sunday Independent article of 9 August 2020 which analysed the hostile coverage of Hume in 1993/94. Fanning, however, was probably making a general comment about O’Reilly rather than suggesting that O’Reilly was put under pressure by London in 1993-94 to get the Sunday Independent to take another line on this particular issue.

O’Reilly may one day clarify precisely what did happen – if anything – in 1993-94 in so far as pressure from London was concerned.

At least John Major’s position is clear. Recall that the attacks on Hume in the Sunday Independent reached their high point in August of 1993. Major covers the lead up to, and aftermath, of this very period in his autobiography where he wrote that:

“In February [1992] John Hume gave the Northern Ireland Office a different version [setting out the principles for an eventual settlement in a way which would attract the Provisionals], which seemed to have come from Sinn Fein. It did not take us long to consider these texts. They were utterly one-sided, so heavily skewed towards the presumption of a united Ireland that they had no merit as a basis for negotiation. They were little more than an invitation to the British government to sell out the majority in the North, and the democratic principles we had always defended. An Irish official privately acknowledged that the Provisionals were not aiming at general acceptability. Their aim was to unite the Irish government and the SDLP in a pan- Nationalist front in order to negotiate Northern Ireland’s future with the British government over the heads of the Unionists. I was frankly surprised that John Hume and Charles Haughey, both very experienced politicians, should have lent themselves to such an unrealistic approach. They must have known that a settlement without the Unionists would be no solution. Nevertheless, the approach was interesting in one respect; with other intelligence, it suggested that some leading Provisionals were groping for a way out of terrorism and into talks.” [p. 447/8 John Major, the Autobiography].

In September 1993 things were still stalled when:

“John Hume came to see me with a parallel message [to that of the Irish government]. It was still take it or leave it, which didn’t require much thought on our part.

“The process was stuck, and its chances were then set further back. Against Reynolds’s wishes, and to increase pressure on us both, Adams and Hume issued a joint statement on 25 September 1993 that they had made considerable progress, were forwarding a report to Dublin, and were suspending their dialogue pending “wider consideration between the two governments”. The ball was placed publicly in our court; and yet the prospect of securing Unionist agreement to anything emanating from Adams and Hume was nil. Dublin did not even send the report to London.” [p. 449/50]

It is therefore unlikely in the extreme – to the extent of being a nonstarter – that O’Reilly was asked by London to put an end to the anti-Hume bombardment by Conor Cruise O’Brien or anyone else in the paper for that matter. It is far more likely that the Home Office and MI5 were delighted with the onslaught. Recall that at this time Taoiseach Albert Reynolds, 1992-94, became so concerned about the hostility of MI5 that he told British PM John Major to ignore what MI5 was telling him and that he – Reynolds – would keep him straight about what was really happening in Ireland.

In January 1972 Bloody Sunday drove many Nationalists into the ranks of the IRA and made Hume’s ambitions to achieve a just peace much more difficult than it needed to be.

Had Mooney and the IRD succeeded in destroying Hume later in 1972, the boost to the Official IRA and the Provisionals would have been immense.

Britain’s politicians, soldiers, spies and police would continue to make mistakes, yet Hume never gave up.

A particular low point was 1974 when rogue elements in MI5 helped the UWC tear down the Power-Sharing Executive of which Hume was a minister, yet again playing into the hands of the extremists. Still, Hume did not give up.

Despite all these set backs, and the fact that the SDLP boasted many of the finest politicians of the Troubles, Hume not only survived but emerged as their real star on the international stage. He became Leader of the SDLP in 1979.

Although the 1974 Executive was not a success, it did set a marker for the Good Friday Agreement (aka ‘Sunningdale for slow learners’) which Hume helped bring about.

Hume then went on to win not only the Nobel Peace Prize (with David Trimble) but the Ghandi Peace Prize and the Martin Luther King Award. No one else has achieved such a feat. In 2010 he was named ‘Ireland’s Greatest’ in a poll conducted by RTE to find the greatest person in Irish history. In 2012, Pope Benedict XVI made him a Knight Commander of the Papal Order of St. Gregory the Great. Hume gave the money he won from these prizes to charities in his native Derry, an indication of his real character.

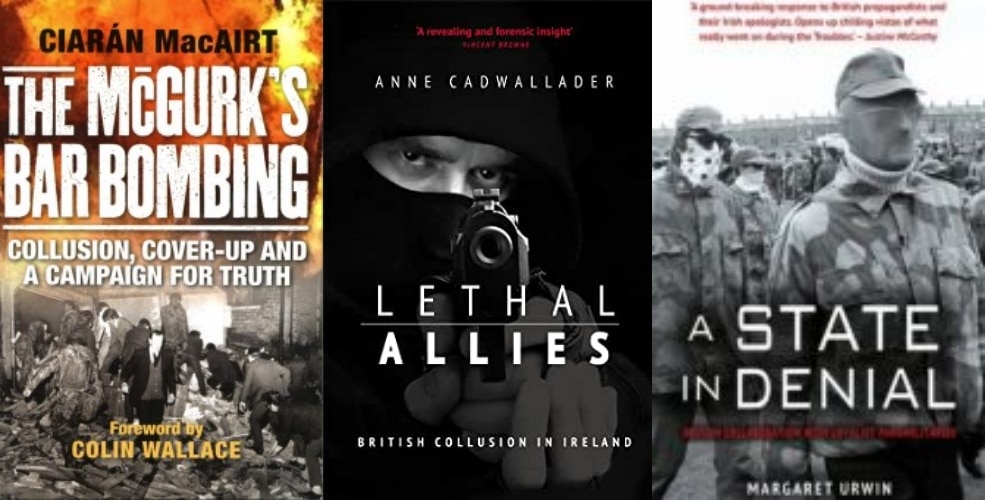

The dirty tricks deployed against John Hume which are described in this article are examples of a pattern of behaviour which demonstrate that the British security and intelligence community is inept and short sighted. Ultimately, the damage occasioned to Hume by the various smear campaigns was negligible. The damage to Britain’s reputation, however, will last for decades, if not centuries, especially when these facts are recorded alongside the multitude of known dirty tricks perpetrated by MI5, MI6, the IRD, the MRF, FRU et al and their associates in the UDA/UFF, UVF and Red Hand Commando. The record includes the following 36 scandals:

- the deployment of the Littlejohn brothers who were sent by Maurice Oldfield to the Republic of Ireland to conduct assassinations, rob banks and attack Garda stations to panic the Irish government into taking tougher measures against the IRA;

- the probable bombing of Dublin in December 1972;

- the theft of classified secrets from the Irish government;

- the interception of Irish diplomatic traffic by GCHQ;

- the torture of prisoners including the ‘Hooded Men’;

- the threat to Nationalists (some of whom were not involved with paramilitaries) that unless they became informers, they would be murdered by loyalists. Other coercive methods were also used to force non-Paramilitaries to become spies and endanger their lives;

- the Ballymurphy massacre of 1971 during which British soldiers shot dead unarmed civilians who posed them no threat;

- the Bloody Sunday massacre of 1972 and thereafter the Widgery Tribunal which covered up the murder of unarmed and peaceful civilians who were misrepresented as terrorists;

- a series of similar incidents involving the killing of innocent civilians;

- the creation and deployment of MRF murder squads in Northern Ireland, especially Belfast;

- the attempt to murder William Black, a police reservist who stumbled upon an attempt by the MRF to steal a car to use on one of their operations (see ‘Ambush at Tully West’ by Kennedy Lindsay);

- the black propaganda emitted after the bombing of McGurk’s Bar to portray the victims of the bombing as terrorists (a tactic similar to that used after Bloody Sunday);

- collusion with Loyalist murder gangs including the provision of arms and intelligence to them to assist them in the murder of Nationalists;

- the protection of the Loyalist terrorists responsible for the Dublin and Monaghan bomb massacre of 1974. These men were recruited before these bomb atrocities and reported to the RUC special branch;

- the plot against the Power-Sharing Executive of 1974;

- the exploitation of the child rape gang that revolved around Kincora Boys’ Home to {i} spy on Unionist politicians {ii} gather information to undermine their reputations and {iii} to recruit and/or blackmail them. See: The Anglo-Irish Vice Ring. Chapters 1 – 3.

- the exploitation of Kincora to recruit vicious Loyalist terrorists such as John McKeague of the UVF/Red Hand Commando The Anglo-Irish Vice Ring Chapters 8 – 10

- the establishment of a brothel called the Gemini in Belfast for intelligence gathering purposes;

- the cover-up of the murder of Seamus Ludlow by the Red Hand Commando;

- the murder of John McKeague by MI5 agents in the INLA after McKeague threatened to expose MI5’s role in the Kincora scandal;

- the misleading of parliament about Operation Clockwork Orange which had involved dirty tricks;

- the penetration and corruption of An Garda Siochana;

- the attempt to recruit Irish Army officers;

- the plot to topple Harold Wilson and other Labour politicians such as Edward Short and Dennis Healey, aspects of which involved intelligence dirty tricks in Northern Ireland;

- the dirty tricks used to end the career of Capt. Fred Holroyd who refused to engage in illegal activities on behalf of MI5;

- the unfair dismissal of Colin Wallace from his post as a psychological operations officer after he tried to expose the Kincora scandal. Wallace was later compensated for the dirty tricks deployed by Ian Cameron of MI5 in the scandal;

- the framing of Colin Wallace for manslaughter with the aid of perjury from a Home Office pathologist. The guilty verdict was subsequently overturned;

- various shoot-to-kill programs including those perpetrated by the RUC, Robert Nairac and others;

- the Stalker affair which involved the smearing and destruction of the career of the Deputy Chief Constable of Manchester John Stalker who was tasked with investigating the RUC shoot-to-kill program,

- the attempt to derail the Stephens Inquiry by lies, non co-operation and an arson attack on his office;

- the Scapaticci scandal which involved, inter-alia, the murder of IRA members to permit British agents ascend through the ranks of that organisation;

- the various murders arranged by Brian Nelson of the UDA in concert with the British military intelligence unit known as the Force Reconnaissance Unit or FRU;

- the murder of Patrick Finucane http://ThatcherThatcher’s Murder Machine, the British State assassination of Patrick Finucane;

- the recruitment and manipulation of journalists on both sides of the Irish border;

- the smearing of Fianna Fail politicians in the Republic of Ireland;

- the plots to smear and murder the former Irish Taoiseach Charles Haughey via the Red Hand Commando in Dingle by blowing up his yacht in Dingle in the summer of 1981. The man from MI5 ‘asked us to execute’ Haughey

- MI5’s attempts to derail the peace process that led to Taoiseach Albert Reynolds having to urge PM John Major to ignore the advice they were giving him;

The foregoing list is by no means exhaustive. Undoubtedly, Britain will have to endure decades of scandals yet as new facts emerge.

Richard Moore, the new Chief of the MI6, Britain’s overseas intelligence service, is the grandson of an IRA veteran of the War of Independence. Hence, he should have some understanding of the complexities of Irish affairs. In fairness to Moore, he did not join MI6 until 1987 after most of the events described in this article had occurred. Nonetheless, he could have MI6’s file on Hume delivered to his desk by clicking his fingers. Thus armed, there could be no better start to his career as ‘C’ than by reading the Hume dossier together with some of the files which deal with the other scandals referred to above. In particular, he might reflect upon the fact the real John Hume gave considerable sums of his money to charity – including the £250,000 from the Nobel Peace Prize – while the IRD/MI6 smear campaign tried to portray him as a thief who stole from charity. Such an exercise might provide a salutary lesson in how dirty tricks do not solve the type of problems his service may have to address, frequently backfire and invariably tarnish Britain’s reputation. Such an exercise might also help preserve him from the moral black hole into which so many MI6 officers fall and was so ably described by Anthony Cavendish in his book ‘Inside Intelligence’.

The same advice might enlighten the new Director-General of MI5, Ken McCallum.

Readers interested in learning more about the career of Hugh Mooney can visit the above-mentioned article: Licence to deceive.

See also Her Majesty’s Smearmeisters: how MI5 and MI6 vilified Haughey, Hume and Paisley This article primarily deals with the smear campaigns MI5, MI6 and the IRD ran against Charles Haughey with the deployment of similar tactics to those hurled at Hume.

The two page document below is a copy of the IRD’s briefing paper used to smear the civil rights movement in the early 1970s.